Nobody is going to dig up Billy the Kid. Nor his Mom.

Nobody is going to dig up Billy the Kid. Nor his Mom.

And anyone who still wonders if young Billy was killed 123 years ago by Sheriff Pat Garrett—as history teaches—or cheated death and lived to old age in Texas or Arizona will just have to keep wondering.

That’s the word out of New Mexico, where the effort to exhume the bodies of the Kid and his mother, and use their DNA as a final arbiter of the truth, has turned into a dud.

In the meantime, things have gotten very nasty. As the Lincoln County News put it, one confrontation was so volatile that “had words been bullets there would have been several casualties.” And a popular statewide columnist has labeled the effort “The Lincoln County Hoax.”

A Lincoln County commissioner (accused of having “his panties in a wad”) has called the effort “an embarrassment.” And it’s not just words; one of the sheriffs pushing this quest is facing recall, while the other’s term of office expired December 31.

Things haven’t been so hot in Lincoln County since Billy the Kid broke out of jail there in 1881, killing two deputies on his way out of town to Fort Sumner, where on the hot night of July 14, Sheriff Garrett supposedly shot him dead and then quickly had the body buried.

Ever since, there have been rumors that Garrett killed someone else and passed the body off as Billy’s; that Billy moved to Arizona, called himself Jim Miller and had a nice life on a ranch before being buried in a state cemetery; or that he moved to Hico, Texas, and called himself “Brushy Bill,” coming back to New Mexico in the 1950s to reveal himself and ask for the pardon the Kid had been promised back in the days when New Mexico was still a territory.

In June 2003, in a move that got front page headlines around the world, Lincoln County Sheriff Tom Sullivan announced it was time to put all the stories to rest. He launched an “official murder investigation,” declaring that DNA tests would prove once and for all what happened that July night.

He also announced a renewed effort to explore a pardon for Billy, and some still have high hopes that will happen. Sullivan tells True West that Gov. Bill Richardson “has promised a hearing on the merits” of the pardon. And the governor’s press secretary, Billy Sparks, confirms the promise. “We’ll hold a hearing to evaluate the evidence and newly uncovered documents,” he told us, including correspondence between Billy and Territorial Gov. Lew Wallace, who originally promised the Kid a pardon.

At press time, we were told the pardon hearing could take place as early as mid-November, probably in Lincoln County. (Watch future issues of True West for a complete discussion of the pardon request and for the results of that hearing.)

Inquiring lawmen

In announcing his attention-getting project, Sheriff Sullivan noted the patches worn by his department depict Pat Garrett, under the premise that the guy was a hero. But if the “real Billy” stories are true and Garrett was a murderer, Sullivan didn’t want to be wearing his face all over town. Helping him was his “deputy” Steve Sederwall—who, it turns out, is not a sworn deputy but something called a “reserve” deputy, a title that doesn’t appear in state law.

They were joined by DeBaca County Sheriff Gary Graves, whose domain includes the town where Billy’s grave is the major tourist attraction. It wasn’t as though the Fort Sumner Village Council had never heard an ex-humation notion before—it fought off efforts in 1962 to rebury the Kid in Lincoln County. (Interestingly, the judge ruled then that “due to the lapse of time and natural causes,” it was no longer possible to accurately locate the grave of Billy the Kid.) Then again in 1981, the council denied efforts to unearth the Kid. They were no more disposed to such an idea this time around, and some want to recall Sheriff Graves because he has pushed the idea. (Sheriff Graves promises, “I’m going to fight them all the way. I’m not giving up.”)

Let us not forget that Gov. Richardson endorsed the project, saying the search for the truth was a worthy cause and promising his office’s cooperation (and if it helped tourism, so much the better).

Everyone hired attorneys—the governor appointed one to represent Billy the Kid—and once the issue faced the light of a courtroom, things went south.

First off, last summer a judge dismissed efforts to exhume Catherine Antrim’s body—the reality is that it’s anybody’s guess where her remains remain, except to say they’re somewhere in Memory Lane Cemetery in Silver City. Then in September, another judge dismissed the effort to dig up Billy “with prejudice,” meaning it can’t be refiled.

Sparks from the governor’s office noted there was a second basic problem: “There was difficulty in trying to exhume the remains without disturbing other remains. The governor was pleased that part of it was dismissed.”

The honchos behind the effort aren’t saying much. “We withdrew our request to exhume the Kid’s body and we’re going in a different direction,” says Sheriff Sullivan, refusing to comment on where that direction takes them. “We have to sit tight for a while.”

Meanwhile, Sheriff Graves says plainly, “The dig is off—right now we just don’t need to dig up Billy,” and then he, too, refuses to explain.

But it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see where these guys are going. In August, they invited renowned forensic scientist Dr. Henry Lee to take samples of items they think contain blood pertinent to this case: One is a wooden bench said to have carried the body of the Kid; the others are floorboards of the original Lincoln County Courthouse where Billy killed deputy James Bell as he escaped.

The bench belongs to the Pete Maxwell family—the home where Billy was killed—and reportedly has had very little exposure to the elements.

Some news accounts in New Mexico are reporting that whatever samples were collected may be useless, contending blood can’t maintain its markers for 123 years. But True West contacted Dr. Phillip Keen, chief medical examiner in Phoenix, who said, “The blood could last, but it frequently has problems and ends up with bacterial contamination. It would not be a good specimen, but I can’t say you couldn’t do it.”

But Dr. Keen, who grew up in New Mexico and seems well versed on the Billy the Kid legend, asked the obvious: If they don’t have Billy’s DNA—which they don’t—what’s the point? “If they have nothing to compare it to, it’s kind of a silly test,” he said.

That’s not dissuading the officers who are pushing this project. “Like Yogi Berra says, ‘It ain’t over till it’s over,’” concludes Sheriff Sullivan, promising to continue the fight as a private citizen.

“I don’t intend to drop this because I’m out of office,” he says. “The private money we raised to conduct this investigation goes with me.” He refuses to specify how much money was donated, or who the donors were—a point that has riled some commissioners who worry about private citizens “buying” criminal investigations. (Some are also livid about the possibility of public money being spent on an old murder case when more recent, open murder cases have yet to be solved.)

Sparks from the governor’s office assures the public that “No state resources have been spent” on this project. “It’s been done totally through volunteer time and private contributions from true West believers.” (We think the reference was deliberate.)

About the only thing that isn’t a mystery in this story is the reaction in some quarters to the demise of the exhumation plans. Controversial columnist Jay Miller (who’s been blasted as a “sleazebag reporter from Santa Fe” by the pro-dig side) reported that after the judge’s dismissal, a big party was held in Fort Sumner’s City Hall, “complete with a banquet of cold cuts, fruit punch and chocolate chip cookies.”

The revelers included Frederick Nolan of England, a major authority on the Lincoln County War; Silver City Mayor Terry Fortenberry; Fort Sumner Mayor Raymond Lopez; and Silver City Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Cissy McAndrew.

“Following the banquet lunch, participants made the five-mile trip south to Billy’s gravesite,” Miller wrote, “where Nolan placed a bouquet of flowers in front of the gravestone of Billy…. Nolan declared the day a victory for truth.”

Such unity—in sharp contrast to the age-old rift between Lincoln and DeBaca Counties—could make something good come out of this after all, Miller editorialized: “People have been talking for years about a Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett historic trail that would circle through our state and join the towns that were part of their history.” Maybe this will “put New Mexicans back on the trail of their unmatchable history of the Old West and its historic sites.”

The way it stands now, Silver City can continue to believe Catherine Antrim is buried in Memory Lane Cemetery (where her headstone is misspelled).

And Fort Sumner can continue to make hay over its major tourist attraction: the official grave of Billy the Kid.

And those who believe the Billy grave is a hoax—that his real remains lie in Texas or Arizona—well, what would a historical mystery be if you had all the answers?

But in the case of Digging Up Billy the Kid, there are no answers. At least not yet.

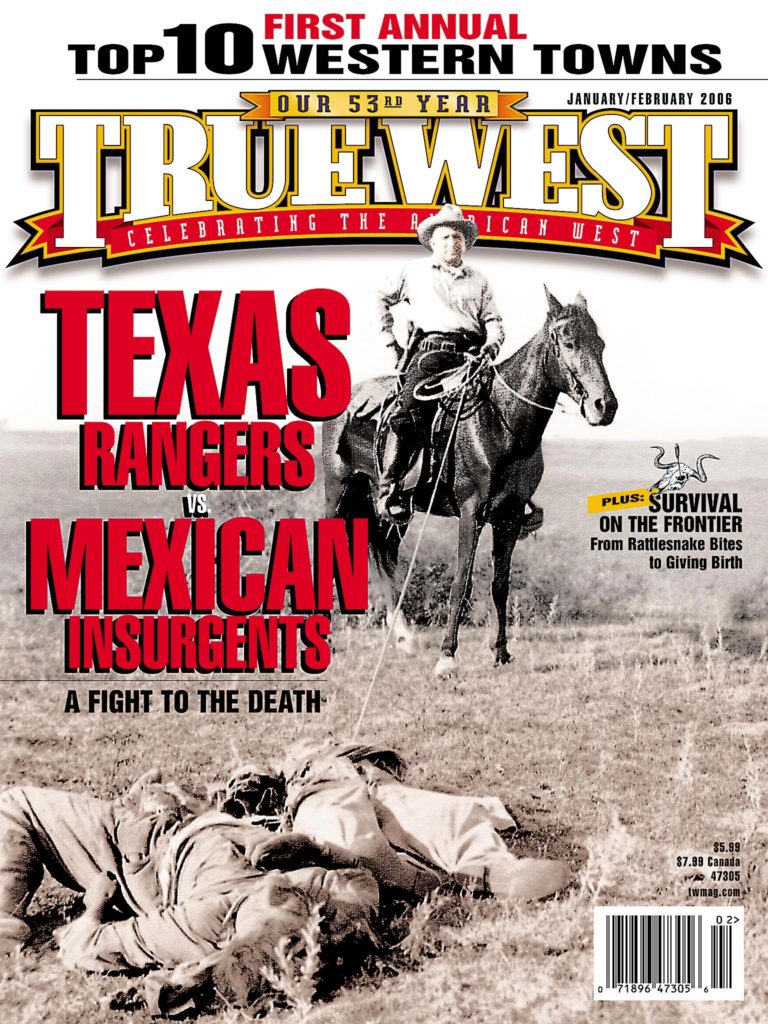

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Carrell Collection, Lincoln County Heritage Trust –

– Illustration by Bob Boze Bell –