Captain Harry Love was in a bad way in June of 1868.

Captain Harry Love was in a bad way in June of 1868.

It had been 15 years since his greatest triumph—tracking and killing the California bandit Joaquin Murietta. The intervening time had not been kind.

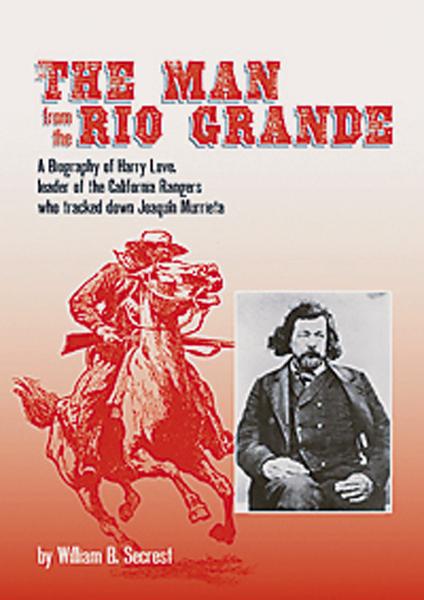

That’s according to a new biography, The Man from the Rio Grande, by William Secrest. It’s the first time Love’s story has been told. And it’s not always a pretty tale.

He lost his farmland in a legal squabble. His sawmill was carried away by flood. His house had burned down. To make matters worse, Love was stuck in a loveless marriage from hell.

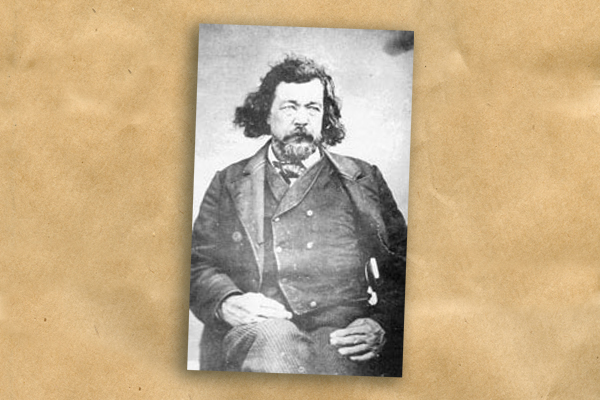

The union between Harry and Mary Love had come later in life for both, in 1854 when he was 41 and she was 51. It was more a joining of convenience than anything else. She’d wanted a strong, protective male—and Love was a bear of a man, well over six feet and 200 pounds. He’d made marks as an Indian fighter, an express rider, an explorer and an outlaw killer. Folks didn’t mess with him. For his part, the captain liked the financial security his wife provided; she was independently wealthy, which allowed him some leeway in finding business success. But by the mid 1860s, the marriage was just a piece of paper. Mary Love didn’t need his protection anymore—in fact, she wanted to get rid of her male burden. Harry successfully fought a divorce action, but he bunked in the barn while his wife got the house located near Santa Clara.

And she was building a new place—a place where Capt. Love would not be welcome. By the spring of 1868, Harry Love was homeless. And it’s likely he was drinking too much, which just fueled his anger and frustration.

Mary made things worse in April when she hired handyman Christian “Fred” Eiversen. He did work that Harry normally would have done. But it didn’t end there—Mary spread the rumor that Eiversen was a bodyguard, protecting her from an abusive husband. Author Secrest is convinced that Love never hit his wife, but the false stories served to further denigrate the old militiaman. He kept coming to the new house, getting into arguments with Eiversen as each ordered the other to leave the property.

Love was hanging around the place on the morning of June 23 when Mary and Eiversen drove up in a buggy, returning from a business trip to San Jose. Harry approached the rig with a shotgun in hand. Eiversen jumped from the buggy with a drawn pistol.

Love went down on one knee behind the sidewalk gate and fired one barrel first, with a few pellets hitting his opponent in the face. But Eiversen kept coming, returning fire and missing. Love let loose with the second barrel before jerking his pistol and pulling the trigger. Eiversen was hit in the arm—but he kept coming. He reached Love’s position and fired a point-blank shot into the captain’s upper right arm, shattering the bone.

Harry ran to the house, looking to escape—but Eiversen kept coming, slugging Love across the head with his pistol. Love went down, and when he tried to rise, Eiversen hit him again. At that point, two men working on the house separated the combatants.

The handyman’s wounds were basically superficial, but Love was in bad shape. Doctors who came to the scene decided to amputate his arm. They gave him chloroform, but it didn’t take full effect to render him unconscious. About 30 minutes after the close of the operation, Capt. Harry Love died.

Ten days later, a local justice found that Fred Eiversen had acted in self-defense. Mary Love had finally gotten rid of her husband, but her relief was temporary. In December 1868—less than six months after Harry’s death—she suffered a heart attack and died.

There was no public funeral for Love. He was interred in the Santa Clara city cemetery; his grave was unmarked and basically lost until the 1980s, when Bill Secrest and others discovered it. In 2003, a memorial was placed at the site, finally giving some closure to the courageous yet tragic life of this man of the West.