“Our journey on will be still more difficult, on account of food. In a few days from this place, buffalo cease entirely, and no game is to be found in the country. To remedy the evil we have to dry and pack meat here for the journey.”

“Our journey on will be still more difficult, on account of food. In a few days from this place, buffalo cease entirely, and no game is to be found in the country. To remedy the evil we have to dry and pack meat here for the journey.”

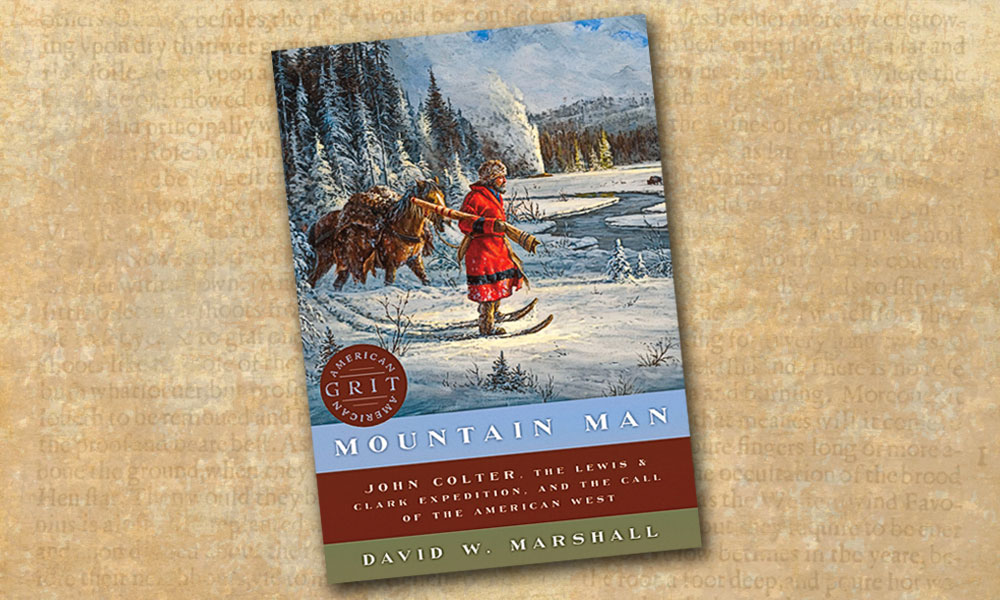

Henry H. Spalding’s sentiment was typical of the Mountain Men, like Kit Carson, who headed to the Rocky Mountains in 1836. They blazed trails across the American West, crossing the Rockies via South Pass, first discovered by members of John Jacob Astor’s fur trading expedition during 1810-12.

To obtain beaver fur for fashionable men’s hats, Astor founded the American Fur Company and its subsidiaries, the Pacific Fur and Southwest Fur Companies. In 1828 he opened Fort Union on the upper Missouri in North Dakota. The post allowed his company to conduct business with Northern Plains tribes.

The main Western fur trading areas included the Upper Missouri, Rocky Mountain and the Pacific Northwest, where Astor established a fur trading post he called Fort Astoria in 1811. We know it today as Astoria, Oregon.

How these men survived continues to amaze me—especially when it came to what they ate. For example, John Bradbury, who headed for the Columbia River in 1810, wrote, “They had nothing to give us as food, excepting some beaver flesh, which Rogers obtained by trapping on Corne du Cerf, or Elk Horn River; as it was stale, and tasted fishy, I did not much relish it, but there was no alternative but to eat it or starve.”

The trappers did buy supplies from the trading posts, but when those ran out, they made do like Bradbury had. Otherwise they ate basic food, like dried beef, pancakes or gallettes from flour and water, while portable soup was a gelatinous mixture made from boiling animal bones. They considered beaver tail, which is very fatty, to be a delicacy.

In contrast to the basic, almost inedible grub the Mountain Men ate, the men at the trading posts and forts dined somewhat differently.

Take Astor’s Fort Union, where the management dressed with jackets for dinner, sitting at tables adorned with white linen, china, silver and crystal. The pantry held canned oysters, champagne, huge barrels of prime hams, butter, eggs, bacon, flour, sugar, molasses, honey, coffee, tea, chocolate, rice, hardtack bread, crackers, a wide variety of vegetables, apples, peaches, plums, raisins, chokecherries, spices, salt and lard. The post also employed a hunter to provide fresh meat, and raised chickens and cattle for food, and a dairy herd for fresh dairy products.

The fort’s cook created a variety of delicacies with the ingredients he had on hand. Rice pudding is one traditional recipe; the 1834 recipe shared here very well could have been eaten by those managing Astor’s Fort Union.

Sherry Monahan has penned Taste of Tombstone, Pikes Peak, The Wicked West and Tombstone’s Treasure. She’s appeared on the History Channel in Lost Worlds, Investigating History and Wild West Tech.

Dutch rice pudding

2⁄3 cup rice

1 cup milk

1 cinnamon stick or sp. ground cinnamon

4 eggs, beaten

tick butter, melted

up sugar

sp. freshly grated nutmeg

Lemon peel, optional

Soak rice in warm water for 30 minutes and then drain. Add the rice, milk and cinnamon to a stock pot and allow to simmer covered for about 20 minutes or until the rice is tender. Remove the cinnamon stick. Allow to cool.

When cooled, add the eggs, sugar and nutmeg, and stir well. Slowly add the butter while stirring. You can line a pie pan with pastry or place directly into a buttered baking dish.

Bake at 375° for about 45 minutes or until the center is set.

***

The December 9, 1834, issue of Arkansas Weekly Gazette