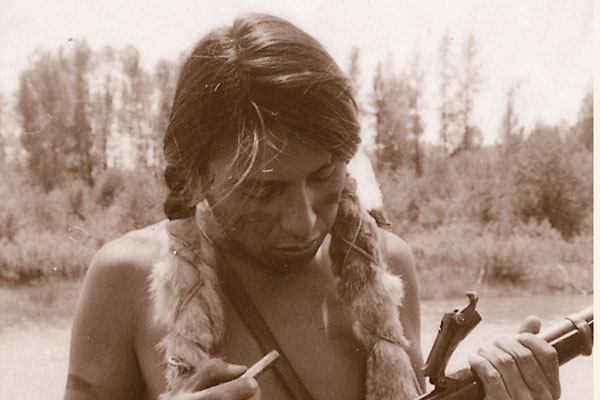

In the heat of battle, the buckskin-clad Alamo defender raises his flintlock muzzleloading musket, takes quick aim at the oncoming Mexican soldados and fires.

But wait … we don’t see the familiar puff of smoke rising from the flinter’s pan and lock area as the musket goes off. What gives? Well, it’s just more movie magic; this time, from 1960’s The Alamo.

With a few exceptions, like the classic film director and firearms enthusiast Cecil B. DeMille, who often employed genuine flinters in his epics, the silver screen filmmakers didn’t feel the need to be as authentic as today’s movie makers do. Due to our increased interest in blackpowder shooting, hunting, re-enacting and other pastimes, modern filmgoers are more familiar with old-time guns than the less knowledgeable, average film buff of more than a half century ago. Filmmakers back then were also limited to using what original, serviceable arms they could obtain. Today, we have the ready availability of authentic replica firearms and accouterments.

For decades, Hollywood films used a number of tricks to make us believe that the actors were firing genuine flintlock firearms. Studios gave a breechloading firearm the look of a flintlock muzzleloader. Working with an 1873 Springfield trapdoor rifle (the studio prop houses had plenty of those), they simply had a dummy brass (with a dull finish) flintlock lock and strike plate assembly cast, then fitted it, via the lock screws, over the original Springfield hammer and lockplate. Sometimes the dummy flintlock hammer and flint piece was soldered onto the hammer, and the immovable strike plate (frizzen) was screwed into the lockplate. With one of these guns, actors used .45-70 caliber blank cartridges, which could be quickly inserted into the breech by simply lifting the hinged breechblock of the Springfield. This tricky bit of movie magic allowed actors relative safety, while giving an authentic look and more firepower to a scene.

The studios also saved time by not having to train each and every actor how to safely and efficiently load and fire a flintlock arm. The weapon was prone to frequent misfires when the user did not properly flint or take care of it. This writer has served as a gun coach for stars like Charlton Heston (1980’s The Mountain Men), Mel Gibson and Heath Ledger (2000’s The Patriot), teaching them the proper handling techniques of flintlock muskets, pistols and rifles—and I can attest that it does take time to train actors.

The next time you see epics that feature large battle scenes with flintlocks, like 1940’s Northwest Passage, 1955’s The Last Command, 1962’s How the West Was Won and Errol Flynn’s swashbuckling adventure The Sea Hawk from 1940, remember: If you don’t see the flintlock puff of smoke at the lock, it is just movie muzzleloading magic.