Emma Cowan awoke early the morning of August 24, 1877, to the sound of strange voices coming from outside the tent she shared with husband George on their vacation in Yellowstone National Park. Peering from under the canvas, Emma saw Indians.

Emma Cowan awoke early the morning of August 24, 1877, to the sound of strange voices coming from outside the tent she shared with husband George on their vacation in Yellowstone National Park. Peering from under the canvas, Emma saw Indians.

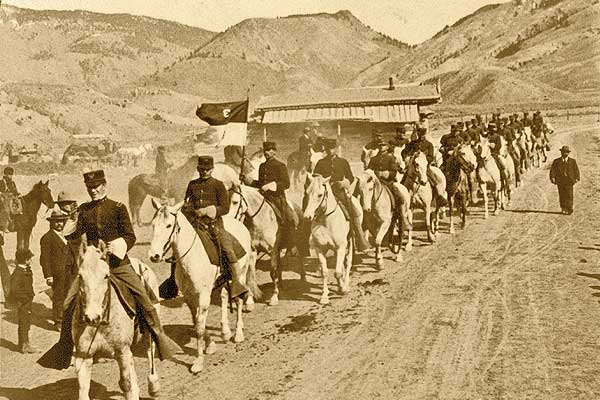

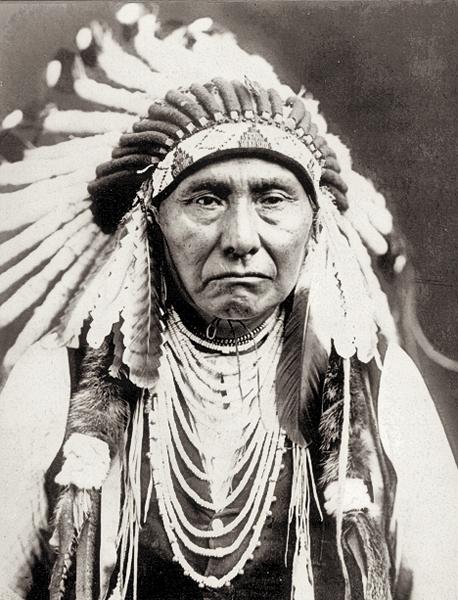

She knew immediately they were Nez Perce, probably the vanguard for the 700 or so tribal members who had fled the reservation in Idaho two months earlier, desperately seeking sanctuary from Gen. Oliver O. Howard and a great federal army who relentlessly pursued them. She didn’t know that, before the day was over, she would meet Chief Joseph, the most recognized of the Nez Perce leaders.

Treaty councils in 1863 set up the events of 1877 when the final steps were taken to force the Nez Perces to relocate from their homelands across the Columbia Basin to a much smaller reservation centered at Lapwai, Idaho. By late May 1877, Chief Joseph, the people who followed him and other bands of Nez Perces began moving toward Idaho. Just days before they would reach Lapwai, a young Nez Perce and his warrior partner attacked and killed some white settlers. Soldiers retaliated in the opening battle of the Nez Perce War that began at White Bird Creek on June 17, 1877.

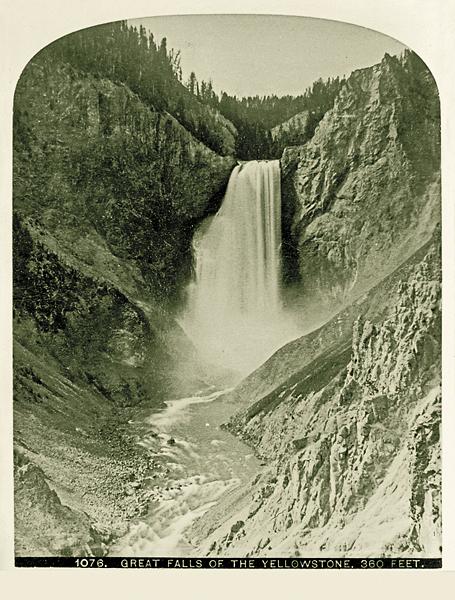

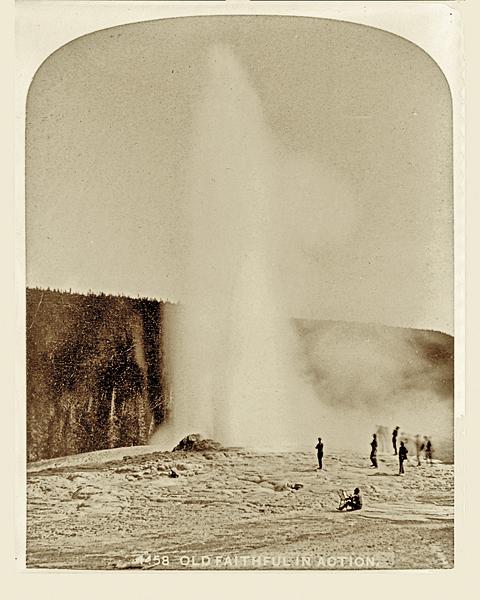

That Montana summer of 1877 was hot and dry, the weather contributing to a grasshopper plague. The insects irritated 23-year-old Emma as they invaded her house in Radersburg, in central Montana near Helena, so when her husband, George, a prominent attorney and former United States marshal, suggested a vacation to Yellowstone National Park, she readily agreed. The park had been established just five years earlier but had already attracted visitors anxious to see geysers, boiling springs, bubbling mudpots and wildlife. Emma invited her 13-year-old sister, Ida Carpenter, and brother, Frank, 27, to accompany the couple. They entered the park on August 9.

At dawn on that very day, troops led by Col. John Gibbon attacked the Nez Perce camp at Big Hole in western Montana, killing more than 80 Indians. Chief Joseph almost single-handedly saved the horse herd during that attack, and then with Lean Elk, organized the families and fled the scene.

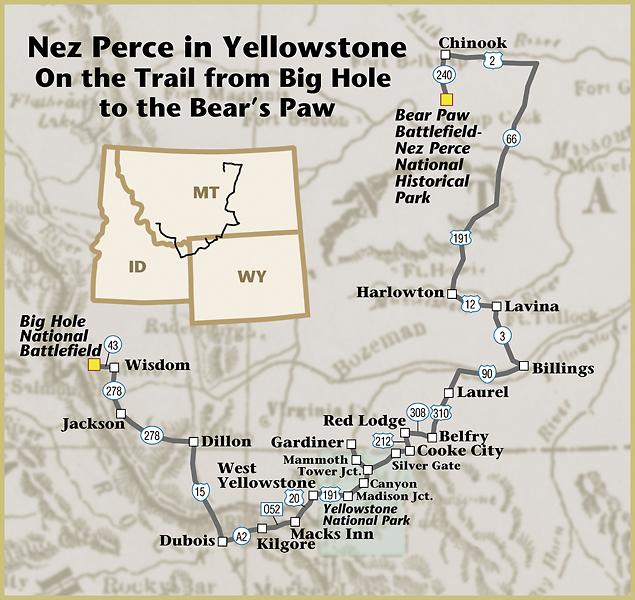

For this Renegade Roads trip, my route starts at the Big Hole National Battlefield, just west of Wisdom, Montana, where the visitor’s center has a small but important collection of artifacts, and a view of the battlefield and camp. The better way to understand this place, though, is to walk the site. Tipi poles mark the locations of the camp.

A Surprise Attack in Geyserland

From Big Hole, the Nez Perces traveled south into Idaho Territory, making it to the region of present-day Dubois, Idaho, before turning east. You can follow their route by traveling across the Big Hole Valley, through Wisdom, Jackson and Dillon, Montana, and then continue toward Dubois, Idaho, near the site of the Camas Meadows Battle.

The soldiers pursued the Nez Perces and engaged them in battle at Camas Meadows on August 20. Then the Indians continued east but also turned north. They were headed toward the country of the Crow Indians, whom they believed would provide a refuge from the continual pursuit of the army that Howard led.

Unaware of the attack at Big Hole in Montana, Emma and her family spent two weeks fishing, hunting, camping and exploring Yellowstone. By August 23, the tourist party had gathered at its main camp in the Lower Geyser Basin, at the location of Fountain Flats just north of Old Faithful, and spent what they expected to be their last night in the place they called “geyserland,” sitting around the campfire, singing and telling stories.

Meantime the Nez Perces had reached the Madison River Valley and followed the river into Yellowstone where they surrounded the Cowan camp. They shot George in the leg and then in the head, and threatened the others (some men with the Cowan party escaped).

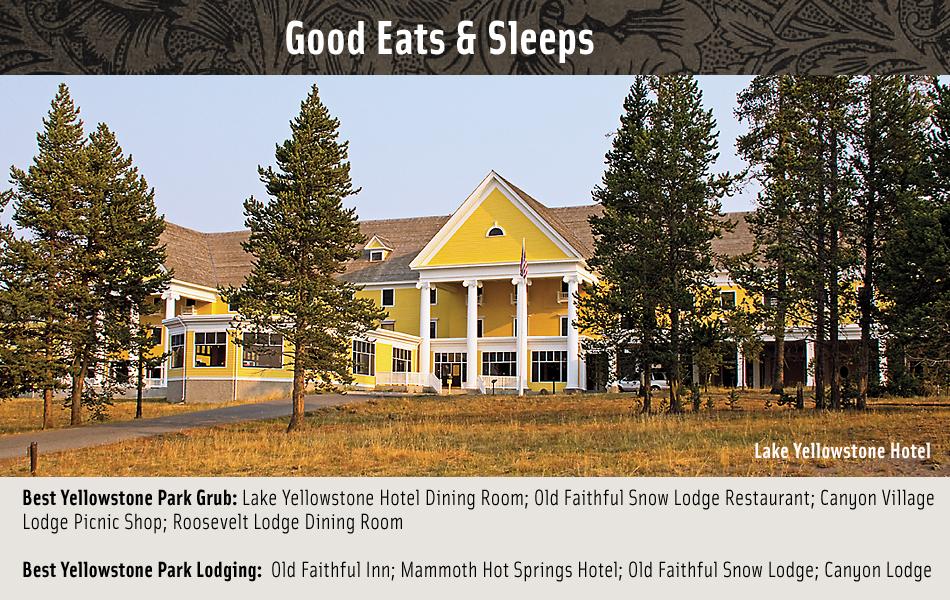

To follow the trail of the Nez Perces in Yellowstone, drive east from West Yellowstone along the Madison River to Madison Junction and then turn south toward Old Faithful and the Fountain Paint Pot trail. This is the area where the Cowan party was camped when the Nez Perce scouts found them.

Lean Elk and Red Scout, who had followed the tourists to see to their safety, came upon the attack and stopped the young warriors from further harming the tourists. With Red Scout’s help, Lean Elk took Emma, Frank and Ida back into custody, leaving George, who was presumed dead, beside the trail. The Indians traveled mostly east until they camped, most likely in the Glen Africa Basin east of Mary Mountain. There, Emma found herself near the campfire of Chief Joseph, whom she later said was “somber and dignified.”

After their encounter, they traveled north to what is now Nez Perce Creek, and my route also backtracks to that creek. While the Indians and captive tourists would head overland toward Mary Mountain, my route is on the highway north to Norris Junction and then east to Canyon.

Burning Bridges

My most recent trip to Yellowstone was a learning seminar I did with the Nez Perce Trail Association, and we camped at the Canyon Campground. We hiked and toured various Nez Perce sites.

One day we traveled north over Dunraven Pass to Tower Junction and then parked the vehicles at a small lot just east of the Yellowstone River, before following a trail along the river that took us to the site of Baronett’s Bridge that had spanned the river until some of the Nez Perce scouts burned it to render it unusable to the army pursuing the fleeing tribe. On our hike, we located the bridge abutment and could see the burned timbers that have survived all these years.

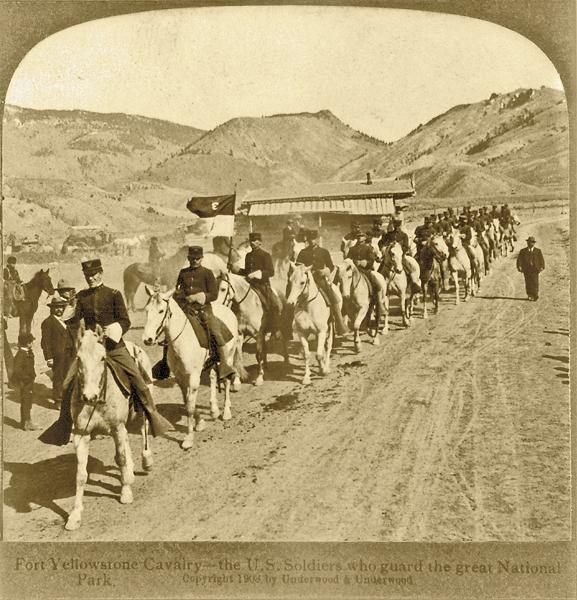

While the Nez Perce scouts were in Yellowstone that summer of 1877, they ranged throughout the park. Some ventured north to Mammoth, where they raided McCartney’s Hotel, shooting one man who had originally been with the Cowan party, before continuing north to the Henderson Ranch (just outside the park), where they gathered horses and provisions. Today in Mammoth, visit the Albright Visitors Center, where you will see original paintings of the park done by Thomas Moran, as well as other artifacts of the early days in the park.

The Heritage and Research Center in Gardiner, Montana, just north of Yellowstone, is a small, new interpretive center with a significant collection of Nez Perce items and other park artifacts. Some are on display and others in storage, however, this is a repository where you can see the deeper collections during behind-the-scenes tours (call ahead to check times and days for the tours).

Running Free in Pelican Valley

The Indian trail next crosses into the open meadowland of the Hayden Valley and turns south to the area of Mud Volcano.

In 1877, the Nez Perces and their tourist captives camped near Mud Volcano (located between Fishing Bridge and Tower Junction) before fording the Yellowstone River and moving into the Pelican Valley. In camp near the river, the Indians made the decision to release the Cowan siblings. The following morning, Lean Elk gave them two horses to ride, helped them cross the Yellowstone River, showed them a trail and told them to “go quick.” The young people made their way north steadily but cautiously until they met a military scouting party.

The time spent in Yellowstone was pivotal. It allowed the Nez Perces an opportunity to rest a bit and their horses to gain strength from the native grasses. The troops pursuing them found the injured George, ultimately reuniting him with his wife. The soldiers also camped near Mud Volcano, where they bathed and washed their clothing in the hot mineral springs before using the Yellowstone River ford and tracking the Indians across the Pelican Valley.

Today, if you go to Yellowstone to visit the places where the Nez Perces traveled in the park, you can also recharge your batteries a bit, particularly if you take time to hike some of the trails or perhaps take a horse packing trip through the Pelican Valley and along the Lamar River.

Hoping for Refuge

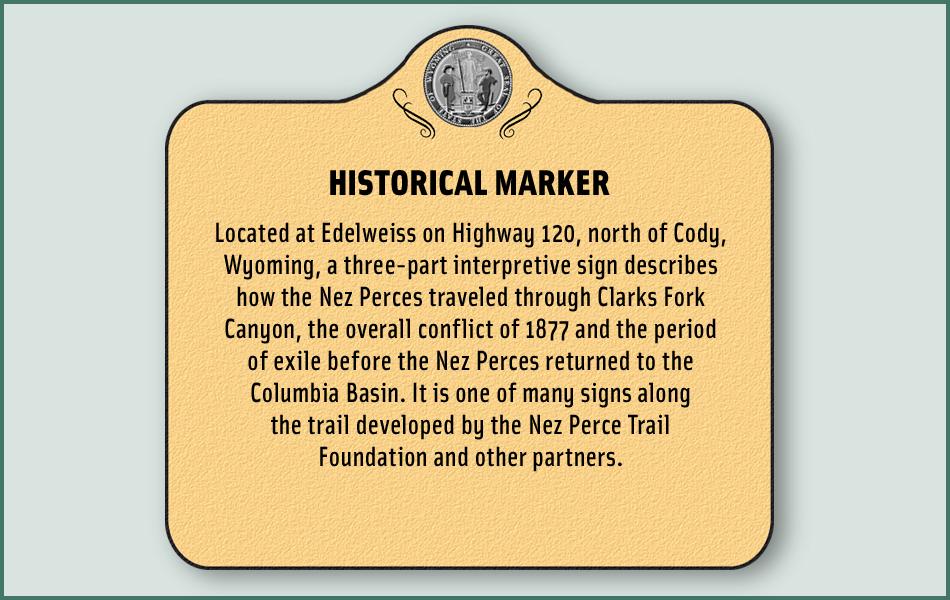

When the Nez Perce families turned toward the Crow lands, they traversed Pelican Valley and crossed Mist Creek Pass before following the Lamar River north. The roaming Indian scouts ultimately came together with Chief Joseph and the main band of Indians as they all gave the army the slip when they took a route through the rugged Clarks Fork Canyon that led the fleeing tribe back into Montana.

While in Yellowstone, the tribe learned there would be no refuge with the Crow Indians. The Nez Perces headed north toward the Missouri River and their next hope for refuge, this time with Sitting Bull in Canada.

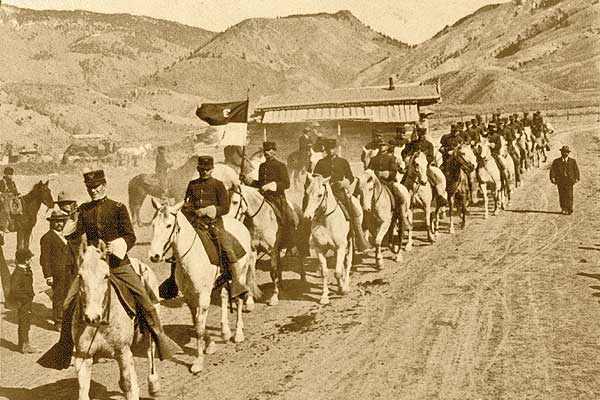

They almost made it. Just 40 miles from the Medicine Line, a second army force led by Col. Nelson Miles overtook the Nez Perces, pinning them down for five days before Chief Joseph surrendered his gun and uttered the defining statement of his life: “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Some tribal members did reach Canada, but those with Joseph would ultimately be relocated to Indian Territory for several years before being allowed to return to Idaho and Washington.

The war ended with Joseph’s surrender to Gen. Howard and Col. Miles, on October 5, 1877, at Bear Paw in Montana Territory. Between August 9 and that day of surrender in October, the Nez Perces—including women, babies, old people, children, warriors—fled 1,500 miles, engaged in six major battles and several skirmishes with federal troops, and saw more than a hundred of their family members die.

Candy Moulton is a lifetime member of the Nez Perce Trail Association. Visit NezPerceTrail.net to join the organization.

Photo Gallery

Edward Curtis took this photograph of Chief Joseph in Seattle in 1903, just a year before the Nez Perce leader’s death.

The Cowan family was on vacation in Yellowstone National Park to relax and see natural wonders such as Yellowstone Falls (above) and Old Faithful (next slide), when they were temporarily taken hostage in the vicinity of Nez Perce Creek (located between Norris and Old Faithful).

– All historical photos Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All travel photos by Candy Moulton –