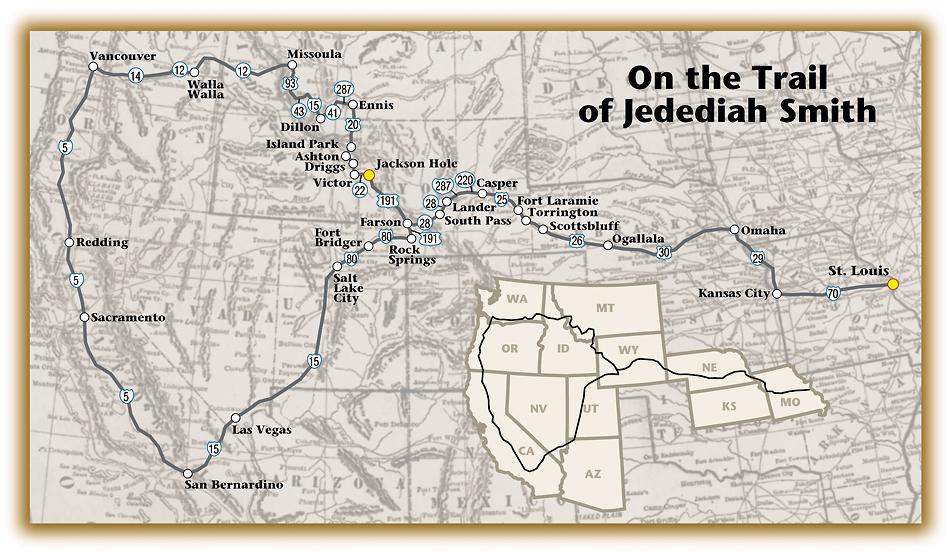

The rugged country on the west side of the Teton Range, between Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, is a wilderness area named for Jedediah Strong Smith, who came west as one of the trappers organized by William Ashley in 1823.

The rugged country on the west side of the Teton Range, between Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, is a wilderness area named for Jedediah Strong Smith, who came west as one of the trappers organized by William Ashley in 1823.

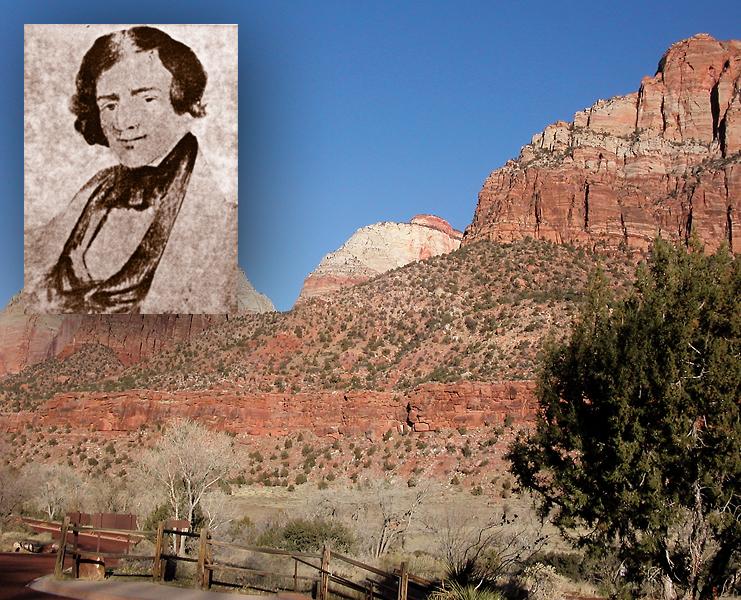

Smith, along with William Sublette and David Jackson, sought beaver in the Rocky Mountain streams, but more than a trapper, Smith was an explorer. He would spend most of his years in the fur trade on expeditions that took him to the Upper Missouri River Country, across Wyoming and into what became Jackson Hole (named for Jackson). As an explorer Smith broke trails through the Rocky Mountains and then pushed into California, Oregon and Washington.

With Jim Bridger, Sublette, Jackson, Thomas Fitzpatrick and a host of other men who would find themselves in the annals of Western history, Smith departed from St. Louis, Missouri, in 1823, one of Ashley’s first crew of mountain men sent upriver to establish a post at the mouth of the Yellowstone. These men would engage in a battle that year with the Arikaras after trading for some horses, and ’Diah would engage in a personal fight with a grizzly bear before heading deeper into the Rockies.

Smith traveled overland across Wyoming in 1824 to “rediscover” the South Pass that Robert Stuart had first located in 1812. This crossing through the Rocky Mountains would become the conduit for hundreds of thousands of overland travelers in the decades to come.

On the west side of the Continental Divide, the Red Desert opens toward the south, and Smith headed there in 1825 to take part in the first rendezvous of mountain men held at Burnt Fork. The Green River Country had free flowing streams filled with plenty of beaver, and Smith trapped across the basin, gathering pelts to trade at rendezvous. A skilled trapper, he became Ashley’s partner. He ventured north into the land surrounded by the Gros Ventre and Grand Teton mountain ranges, some of it land that is now a wilderness area bearing his name.

Ashley, having discovered money could be made in supplying the trappers with goods while trading for the pelts they had collected over the winters, sold out to Smith, Jackson and Sublette in 1826. At the rendezvous on Bear River the new partners agreed that Jackson and Sublette would turn their attention to the valleys and streams to the north, while Smith would move into trapping territory to the south.

In truth Smith had a wanderlust likely stoked from the time he was a child by his family’s continual movement west from New York to Pennsylvania and then to Ohio, seeking out the edge of the frontier on each new settling.

Gateway to the West

Any trail of the mountain men should start in St. Louis where Ashley advertised for his “young men.” A good place to begin following some of Smith’s trail is at the Museum of Westward Expansion inside the Gateway Arch. Before departing St. Louis, you should explore, shop or dine at Laclede’s Landing, a nine-block district that takes in part of the original trading area for the city of St. Louis.

Leaving St. Louis I head west along the Missouri River through Independence, Kansas City and St. Joseph, towns that grew from the pioneers who followed the trails forged by mountain men. Crossing into Nebraska, I visit the Omaha region to check out the Joslyn Art Museum, home of classic fur trade paintings such as The Surround and Trapper’s Bride by Alfred Jacob Miller, and multiple pieces by Karl Bodmer. The nearby re-created Fort Atkinson interprets the early history of the site that was the first military post west of the Missouri River, established in 1819 upon the prior recommendation of transcontinental explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Rendezvous in Wyoming

No U.S. Army post existed at the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers when Smith first visited what is now Wyoming in 1824, but I recommend a stop at Fort Laramie, which was pre-dated by a fur trade post started by Sublette and Campbell. The fort interprets the era of the mountain men, along with the Indians, pioneers and the frontier military who all had significant roles at this location.

Like Smith, I’m headed west. My route is through Casper, where I visit Fort Caspar—a replica of the frontier military post named for Lt. Caspar Collins who was killed in a battle against Cheyenne and Lakota Indians in July 1865—and the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center, celebrating its 10th anniversary this year. I drive west out of Casper, round Independence Rock and pick up Smith’s trail where I dally for a while at Devils Gate and shoot on up the Sweetwater River Valley past Split Rock headed toward South Pass.

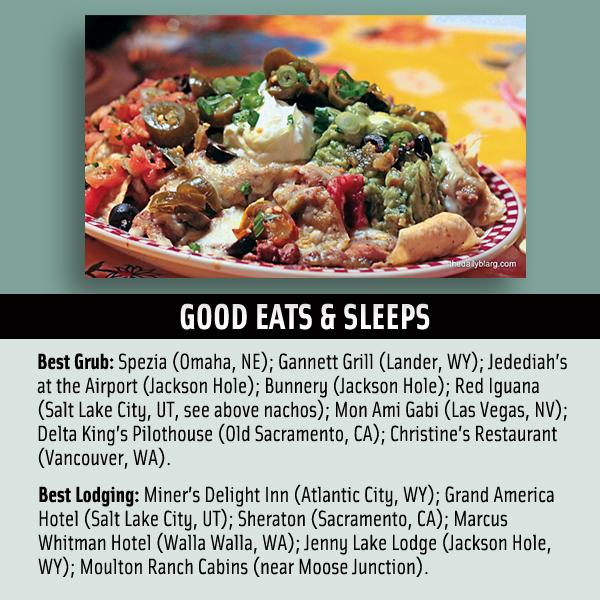

In Lander, I stop to grab a good sandwich at the Gannett Grill. Just a half-hour drive east is Riverton, where, every Fourth of July, a modern-day rendezvous gathers to celebrate the 1838 mountain man rendezvous. The 1830 rendezvous was held nearby on the Popo Agie River, a gathering that was significant in Smith’s Western story, but we’ll get to that later.

Smith came into this country from the Upper Missouri, where he’d wintered in 1823 at Ashley’s post before crossing into what is now Wyoming, traversing the Bighorn Mountains, crossing the Bighorn Basin and descending into the Wind River Basin before ultimately descending the Sweetwater River near Devils Gate and retracing his steps to South Pass. This natural divide west of Lander would become the key to overland migration known for the grade, grass and water along the route.

As you reach this area in your own explorations, I highly recommend a diversion to Atlantic City for a meal at the Merc (as the locals call it) or a stay at the rustic Miner’s Delight Inn. You should also find time to visit South Pass City, a gold boomtown in 1868.

My route, like Smith’s, splits in western Wyoming. First I head to Pinedale for a visit at the Museum of the Mountain Man. The second weekend of every July you can attend the Green River Rendezvous. Then I continue northwest toward Jackson Hole, past the location of six mountain man rendezvous that were held on Horse Creek, near the tiny community of Daniel, during the 1825-43 period. I follow the Hoback River and then the Snake River into Jackson Hole. Locals kick off their summer with a rendezvous at the fairgrounds in Jackson as part of Old West Days on Memorial Day weekend.

Smith was at Burnt Fork in southwestern Wyoming for the first ever fur trade rendezvous held in 1825. He passed through the valley that would ultimately bear Bridger’s name. Although visiting Fort Bridger is a treat any time of year, the best time to visit is over Labor Day weekend when the largest mountain man rendezvous in the Northern Rockies takes place.

Virgin River Country

Enough of rendezvous…it’s time to really hit the road to see some of the country Smith explored. In 1826 he left the rendezvous site along the Bear River in present-day Utah and headed south along the west face of the Wasatch Mountain range, traveling to Virgin River Country.

Following his route today, you should visit the University of Utah’s Natural History Museum of Utah in Salt Lake City, and then stop and see the dinosaur tracks near St. George and the Valley of Fire in southeast Nevada, just southwest of Mesquite.

When Smith traveled this vicinity in 1826, the natural oasis that became known as Las Vegas Springs may have provided much needed water. Certainly that spring (now recognized as the Springs Preserve) served later travelers, including Mormons who settled the region. Today, of course, Las Vegas has dancing fountains (at the Bellagio), a volcano (at the Mirage) and other lights, bells, whistles, attractions and opportunities for entertainment and a good meal. But it is too glitzy for the likes of Smith, known for his quiet demeanor and knowledge of the Bible, a book he carried with him on his explorations.

Great Basin Pioneer

Smith went on to San Bernardino, where he received a welcome at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, but Mexican authorities queried him on what an American was doing in Mexican territory. Ordered to leave, Smith and the men with him recrossed the San Bernardino Mountains, then headed north through the San Joaquin Valley, eventually reaching the American River. Here, Smith left some of his men in camp on the Stanislaus River, while he headed east across the Sierra Nevada to return to the Great Basin and the 1827 mountain man rendezvous, where he arrived worn out and hungry. In his journey he was the first known white man to cross the Sierra Nevada and Great Basin.

After the rendezvous, Smith returned to California, taking his previous route, and engaged in a fight with formerly peaceful Mohaves; some of the men with him were killed. He again became involved in a bureaucratic delay created by Mexican authorities, before finally reuniting with his other men along the Stanislaus River in the vicinity of present-day Sacramento. In that city, you should visit the California State Indian Museum and take a detour northeast to Roseville for a visit to the Maidu Indian Museum.

Recognizing the difficulty in crossing the Great Basin, Smith set out across northern California with a large herd of horses to ultimately follow what would become the Smith River and pass through the forest of huge Redwood trees. Today some of this region is preserved in Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park and the adjacent Redwood National Park near Crescent City. From here Smith continued north into Oregon, following the coast up through the Willamette Valley, which would draw American pioneers one decade later.

Heading up the Columbia

Smith went on to Fort Vancouver, where he and his men were in a region dominated by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Visiting this site today, on the north side of the Columbia River in Vancouver, Washington, you’ll be able to learn about the fur trade company and see relics uncovered in ongoing archaeological excavations in the fort area.

From Fort Vancouver, Smith headed up the Columbia River, ultimately traveling across Idaho and western Montana to Flathead Lake. I like the Washington route along the Columbia on Highway 14, which skirts the river and is lined with vineyards on the drive toward Tri-Cities, where you can continue on U.S. 12 to Walla Walla. Near here Marcus and Narcissa Whitman established a Presbyterian mission just as the mountain man era was ending.

My route across Idaho takes me through Nez Perce Country and over the route traveled by Lewis & Clark in 1805.

Smith went to Flathead Lake and then turned south to head toward the rendezvous held in Pierre’s Hole. My own route is through the Bitterroot Valley and then across the Big Hole and into Pierre’s Hole—today’s Island Park and Teton Basin of Idaho. After two years of exploration, Smith reunited with his fur company partners Jackson and Sublette in Pierre’s Hole in 1829.

Smith organized a fur brigade that moved north into Blackfeet Country, and he ultimately attended the 1830 rendezvous on the Wind River in Wyoming. He, Jackson and Sublette negotiated some important business at that rendezvous when they sold their company to Bridger, Fitzpatrick, Milton Sublette, Henry Fraeb and Jean Baptiste Gervais. Henceforth the enterprise would be known as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

One Last Trade Venture

Following the 1830 rendezvous Smith returned to St. Louis intending to prepare maps and write a book about his travels. But first, he would take one more journey.

In 1831 Smith, as a final commitment to the former partnership with Jackson and Sublette, took a supply caravan west, following the Santa Fe Trail. This would be his last exploration and trade venture. When the caravan was on the dry Cimarron Cutoff, Smith set out looking for a source of water. While thus engaged in that search, Comanches surrounded and killed Smith.

Smith spent less than a decade trapping and exploring in the West, but his adventures had a profound impact on the region. He was the first American to see much of the country. Although he declined to return to—or leave—California by crossing the Great Basin (he believed the area was too dry and difficult for men and animals), the Humboldt River expansion of his 1827 route became the main conduit for thousands of people who were involved in the California Gold Rush.

Spur-winning author Candy Moulton lives and writes near Encampment, Wyoming.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted –

– Jedediah Smith: True West Archives –