Outlaw Treasure – The Dalton Gang Loot

Outlaw Treasure – The Dalton Gang Loot

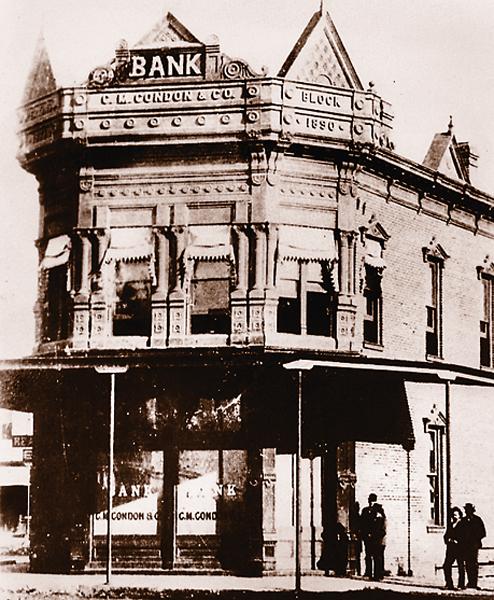

The famous Dalton Gang made history in 1892 when they attempted to rob two banks at the same time in Coffeyville, Kansas. The result was the death of four of the outlaws and four citizens, and a prison term for the only survivor, Emmett Dalton.

Less well known is the fortune in gold and silver coins allegedly buried by the outlaws on the evening before the Coffeyville attempt. The cache was estimated to be worth between $9,000 and $20,000 in 1892 values.

Before their Coffeyville robbery, the Dalton Gang held up a Missouri-Kansas-Texas train near Wagoner, Oklahoma, and another near Adair. From these robberies, they netted $10,000. A few weeks later, they walked into an El Reno, Oklahoma, bank and took $17,000.

Following these robberies, the gang members purchased new saddles and clothes. The remaining loot was carried in their saddlebags as they made their way toward Coffeyville.

On the evening of October 5, the gang arrived at Onion Creek where it joins with the Verdigris River near the Kansas-Oklahoma border. There, they set up camp. Desiring to travel as unencumbered as possible, they unloaded all of the goods from their horses. The gold and silver coins were placed in a shallow hole they dug adjacent to their campfire.

At dawn the following morning, the outlaws breakfasted, checked their firearms and ammunition, and saddled their mounts. Before leaving, Emmett told the gang members that if they became separated, they were to rendezvous at this site, where they would retrieve the coins and escape deeper into Oklahoma.

The robbery attempt was a disaster and spelled the end of the gang. All were killed, save for Emmett. He served only 15 years in prison when he was pardoned in 1907. Lawmen believed that when freed, Emmett would lead them to the buried cache. They followed him for weeks, but he stayed away from Onion Creek. He once told an interviewer that he believed the coin cache was tainted and he wanted no more to do with it.

The precise location of the Onion Creek campsite has been debated for years, but recently discovered information has narrowed the area of search. On the morning the Dalton Gang departed for Coffeyville, Mary Brown, the young daughter of a nearby rancher, was riding her horse when she heard voices near Onion Creek. Reining up her mount, she listened and heard the sounds of men eating and saddling horses. Moments later, Brown saw five horsemen riding out from under a small wooden bridge that spanned the creek and making their way toward Coffeyville.

Years later, when Brown was an adult, she heard the story of the gold and silver coins buried at the Onion Creek campsite and was determined to find them. During the time that passed since the Coffeyville Raid, however, the old bridge had been torn down, portions of the creek had changed course and the road had been relocated. Though she searched for a full day, Brown was unable to find the location where the Daltons had camped so many years earlier.

As far as anyone knows, the treasure is still there.

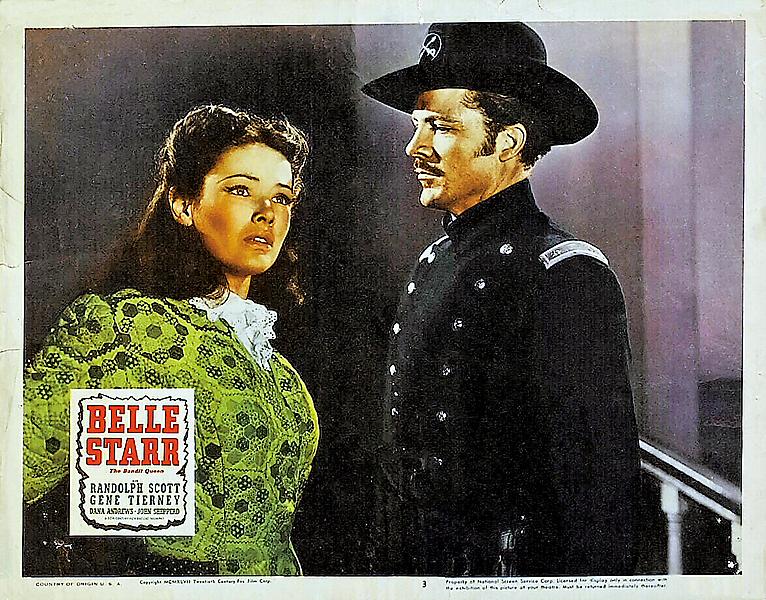

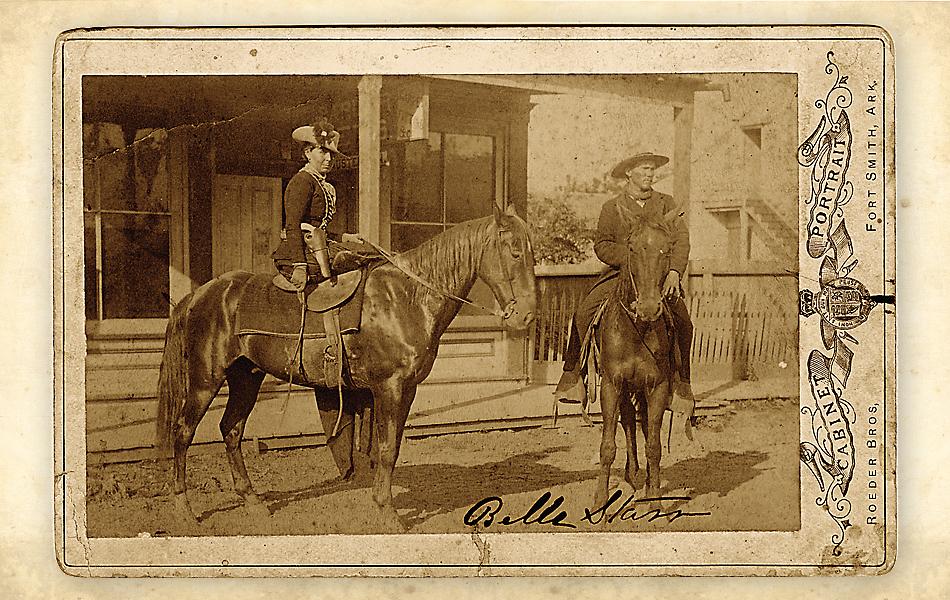

Belle Starr’s Lost Iron Door Cache

Belle Starr was arguably the American West’s most famous female outlaw. She was known to deal in stolen horses, and she provided sanctuary in her eastern Oklahoma home to Frank and Jesse James, the Younger Gang and other notorious banditti. Some believed that she helped plan crimes and aided her accomplices in hiding and spending money taken in bank and train robberies.

A tale that has surfaced over the years involves gang members Starr allegedly knew. They stopped a freight train bound for the Denver Mint during the mid-1880s. The train was transporting a cargo of gold ingots destined to be turned into coin.

Though the robbery went as planned, the gang feared immediate pursuit from federal agents. They decided to hide the gold in a cave in Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains. Before riding away with the loot, gang members removed one of the iron doors from a railroad car and, using ropes, dragged the door along behind them as they made their escape on horseback.

When they arrived at the cave, the bandits stacked the gold against one wall. The iron door was placed over the entrance, wedged into position, and covered over with rock and brush. Before leaving the area, one of the outlaws hammered a railroad spike into an oak tree located 100 yards from the cave.

A short time after the robbery, railroad detectives learned of the possibility that the gold had been hidden in the Wichita Mountains. Though they hunted for weeks, they were never able to find it.

During a subsequent train robbery attempt a few months later, all of the members of the gang were killed. In 1889, Starr was murdered, a crime that has never been solved. With her death, no one remained alive who knew the exact location of what has come to be called the “Lost Iron Door Cache.”

During the first decade of the 1900s, a rancher and his young son rode into a canyon in the Wichita Mountains near Elk Mountain. Their attention was captured by the reflection of the sun from an object located on the eastern slope. On investigating, they encountered a large, rusted iron door set into a recessed portion of the canyon wall. The son wanted to see what was on the other side of the door, but the father reminded him they had to reach their destination before nightfall. Later, the father learned the story of the Iron Door Cache. The two returned to the region, but were unsuccessful in relocating the site.

During the ensuing years, a number of ranchers, hunters and hikers have reported spotting the iron door against one wall of a remote canyon in the Wichita Mountains. On learning the story of the gold, they attempted to return to the location, but could never find it.

While traveling through a remote canyon in the Wichitas in the 1950s, a rancher decided to pause and take shade under a large oak tree. He hung his hat on a railroad spike hammered into the trunk. Familiar with the story of the gold cache and the spike, he made plans to return to the canyon and search for the treasure, but was never able to relocate the site. Later, someone cut down the oak tree for firewood.

The latest sighting of the door was in 1996. A middle-aged man making his way on foot from the small town of Cooperton to Lawton, in search of work, took a shortcut through the Wichita Mountains and spotted the iron door. Three weeks after arriving in Lawton, he learned the story of Starr’s Iron Door Cache. He purchased a few tools and set out to recover the gold. On the way, he suffered a heart attack and died.

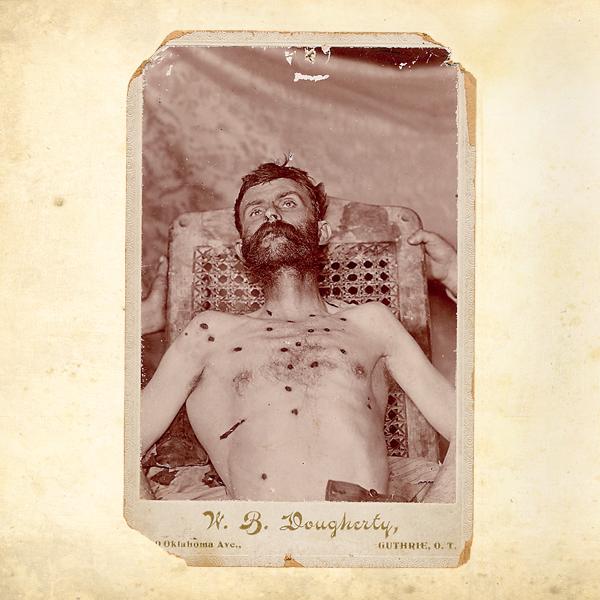

Bill Doolin’s Gold

In spite of lore that claims Bill Doolin netted over $175,000 in robberies in Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas over the two-year period preceding his death, the outlaw lived frugally in a wood frame shack near Burden, Kansas.

In between robberies, Doolin purchased a small plot of land and a shack near Burden, 40 miles southeast of Wichita. To this place he retreated with his loot, and it was here that he buried most of it. He never told anyone about his new residence, preferring to keep it secret.

In December 1895, Doolin traveled to Eureka Springs, Arkansas. An arthritis sufferer, he often bathed in the hot springs to soothe his aches. One afternoon he was arrested by Deputy Marshal Bill Tilghman while soaking in a hot mineral bath. He was placed in the jail in Guthrie, Oklahoma, to await trial for bank robbery. Certain that he would be convicted, Doolin escaped and fled to Burden. He began making plans to move his wife and child to this location.

For days following Doolin’s escape, the Oklahoma countryside was searched for some trace of him, to no avail. One lawman, Heck Thomas, got a tip that Doolin was planning on visiting his wife and son. He learned that Doolin’s family was living in Lawton. Thomas rode to Lawton and, from hiding, watched the house where Mrs. Doolin was living.

Thomas and a posse were hiding out near the house when Doolin came walking up, leading the horse and buggy. The outlaw spotted the lawman and reached for a rifle under the wagon seat, firing twice. Thomas shot him dead.

Doolin’s friends were aware that he buried his share of the robbery loot, but never knew where. Not until 20 years after the outlaw’s death did anyone discover his secret residence in Burden. By that time, the old shack had tumbled down, and the land was covered in weeds and brush.

Though many have searched the area for Doolin’s cache of gold and silver coins, it remains undiscovered.

Sam Bass Treasure

Following a train robbery outside of Big Springs, Nebraska, Sam Bass and other outlaws got away with 3,000 twenty-dollar gold pieces, along with jewelry and money taken from the passengers. After dividing the loot, the outlaws split up. Bass went to his hideout at Cove Hollow near Denton, Texas. Some believe he buried his booty at Cove Hollow, although others believe he just as easily could have spent the money. He soon formed a gang, robbed more stages and added to his caches.

Bass made plans to rob the Williamson County Bank in Round Rock, Texas. When the outlaws stopped at the store first to buy some tobacco, a couple of local lawmen noticed they were armed and started to talk to them. They didn’t recognize Bass. The outlaws opened fire on them, and a gunfight ensued. Badly wounded, Bass escaped.

Texas Rangers caught up with him in a nearby pasture. The outlaw died more than a day later, and with his death went the knowledge of the location of his treasure caches at Cove Hollow.

Henry Plummer’s Lost Gold

In a short span of time, the Henry Plummer gang amassed an impressive fortune in gold coins, ingots and nuggets from robbing stagecoaches, freight wagons, miners and travelers throughout Washington and Montana…at least, according to legend, since no evidence supports the claim. Some historians have made the argument that Plummer was not an outlaw, nor did he lead an organized gang. But for those who believe that Plummer was a gang leader and who also believe in the legend of his treasure, Plummer’s share has been estimated to exceed $200,000.

For a time, Plummer (and maybe his gang) lived near Sun River, 20 miles from Great Falls, Montana. Plummer apparently buried his portion of the gold near a small creek located 200 yards from the house. He never revealed the location.

On January 10, 1864, vigilantes caught up with Plummer and hanged him. In 1875, a young boy was digging in the soft ground near a stream at Sun River and found one of Plummer’s bags of coins. He returned to the area with his father, but was unable to relocate the spot. Plummer’s buried treasure, at its estimated value, would be worth several million dollars today.

Cy Skinner’s Lost Loot

Cy Skinner was among those named as a member of Henry Plummer’s gang. After Plummer was killed, Skinner loaded up the gold ingots and coins he had accumulated in the same robberies—$200,000 worth—and fled to Hell’s Gate (now Missoula), Montana. After reaching his destination, Skinner carried the gold to one of several small islands in the middle of the Clark Fork. Weeks later, a mob of men stormed Skinner’s cabin, hauled him outside and hanged him.

During the 1930s, a man named Taichert found a portion of Skinner’s gold on one of the islands. When he returned the next day to search for the rest of it, heavy rains had caused the river to rise, barring access to the island. By the time the flow receded, the islands had been altered in size and shape. Taichert was never able to find the precise spot where he had found the gold. Skinner’s gold still rests beneath a foot or two of river deposit on one of the small islands.

Outlaw Treasure

Mexican Payroll Loot Austin, Texas

A $3 million treasure, allegedly from a Mexican payroll in 1836 stolen by the paymaster and accomplices, the loot could be buried near Shoal Creek in Texas. After burying the loot and, in turn, killing members of the party, the remaining outlaw returned to Mexico. His map to the treasure shows it was buried five feet underground, close to an oak tree with two eagle wings carved on it.

Eight men dug 40 feet of tunnel for eight months along Shoal Creek, saying they were constructing a new bridge or a large house. On April 13, 1927, according to The Rising Star Record, the workers took off with the loot:

“A box was lifted from the square cut chamber between the rocks, for the next day the workmen were gone and the blasting has ceased. Curious throngs soon found the dark tunnel and with lights discovered traces of the large wooden box that had laid beneath the dirt for more than 60 years.”

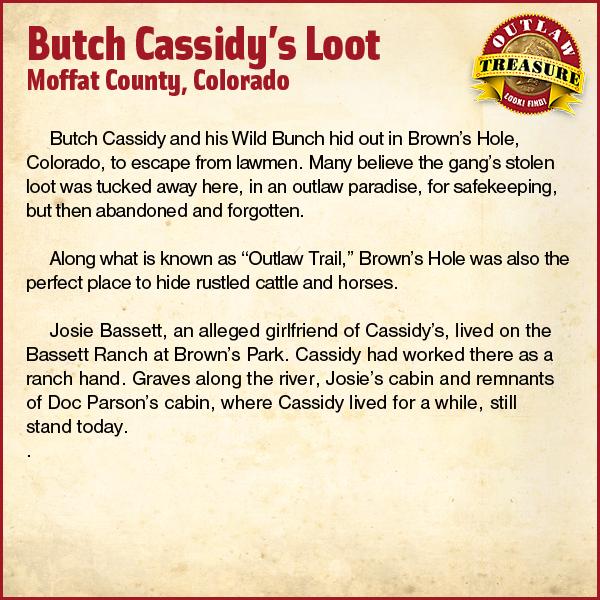

Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch hid out in Brown’s Hole, Colorado, to escape from lawmen. Many believe the gang’s stolen loot was tucked away here, in an outlaw paradise, for safekeeping, but then abandoned and forgotten.

Along what is known as “Outlaw Trail,” Brown’s Hole was also the perfect place to hide rustled cattle and horses.

Josie Bassett, an alleged girlfriend of Cassidy’s, lived on the Bassett Ranch at Brown’s Park. Cassidy had worked there as a ranch hand. Graves along the river, Josie’s cabin and remnants of Doc Parson’s cabin, where Cassidy lived for a while, still stand today.

Lost Opata Mine South of Tucson, Arizona

About 45 miles south of Tucson, Arizona, rises what remains of Tumacacori Mission, now a national park. The 18th-century church was built by Spaniards hoping to convert the pagan Opata and Papago Indians. The missionaries hired the Indians to work in their nearby silver mines and store the yield in a giant room.

The Opata kidnapped a woman they believed was the Virgin Mary and wanted her to marry their chief. She refused, so the people sacrificed her to their gods by tying her to the silver, rubbing poison into cuts in her hands, and dancing and singing around her.

The missionaries, so dismayed by the pagan violation of their Christian teachings, had the entrance closed off, presumably sealing in the woman’s skeletal remains—and all of the silver—still waiting to be found.

Lost Dutchman Mine Apache Junction, Arizona

Rich in gold, but—some believe—cursed, the fabled Lost Dutchman gold mine generates endless stories. The treasure hunters who mysteriously go missing while looking for the gold fuel the 120-plus-year legend. Today, some wonder if the Superstition Mountains really harbor the gold or if the stories have piled upon stories to bury the truth.

Sometime after 1868, a German (not Dutch) miner named Jacob Waltz found the Peralta family mine and worked it with an associate, Jacob Weiser. Legend has it that they hid some of the gold near Weaver’s Needle, a local landmark. Details after that are unclear, according to Lost Dutchman State Park information. Either Waltz killed Weiser or Apaches killed him, leaving Waltz as the only person who knew the whereabouts of the mine.

His neighbor in Phoenix, Arizona, who took care of him before his death in 1891, and countless others have searched unsuccessfully for the gold.

Hidden Treasure

Ruggles Brothers Gold Redding, California

In 1892, the charming, young Ruggles brothers held up the stagecoach to Weaverville, California, just west of Redding, making off with the strongbox loaded with gold. Buck Montgomery, of the Hayfork Montgomery clan, was the armed escort on the stage. He shot at Charles Ruggles, who had ordered the driver to halt.

John Ruggles fired back, killing Montgomery. Thinking his brother was dead, he cached the loot somewhere nearby. Charles was alive, but some of the loot was never found. Eventually, local vigilantes lynched the Ruggles.

Jesse James’s Hidden Treasure Wichita Mountains, Oklahoma

Legend says the James Gang, in 1876, buried stolen treasure in a deep ravine east of Cache Creek in Oklahoma. Jesse James made two signs pointing to the gold: He emptied two six-shooters into a cottonwood tree, and he nailed a horseshoe into the trunk of another cottonwood tree. Then he scratched out a contract on the side of a brass bucket to bound everyone to keep the secret. Although this doesn’t seem in his character to do so, since the written oath could have been used as evidence against him, some folks believe the treasure exists.

The words on the bucket read: “This the 5th day of March, 1876, in the year of our Lord, 1876, we the undersigned do this day organize a bounty bank. We will go to the west side of the Keechi Hills which is about fifty yards from [symbol of crossed sabers]. Follow the trail line coming through the mountains just east of the lone hill where we buried the jack [burro]. His grave is east of a rock. This contract made and entered into this V day of March 1876. This gold shall belong to who signs below. Jesse James, Frank Miller, George Overton, Rub Busse, Charlie Jones, Cole Younger, Will Overton, Uncle George Payne, Frank James, Roy Baxter, Bud Dalton, and Zack Smith.”

The gold hasn’t been found, but the engraved brass bucket and simple map have been, as have the markers pointing to the treasure’s hiding spot.

Calling himself a professional treasure hunter, W.C. Jameson is the author of nearly 20 treasure tomes that share tales of buried treasure all over the American West and beyond.

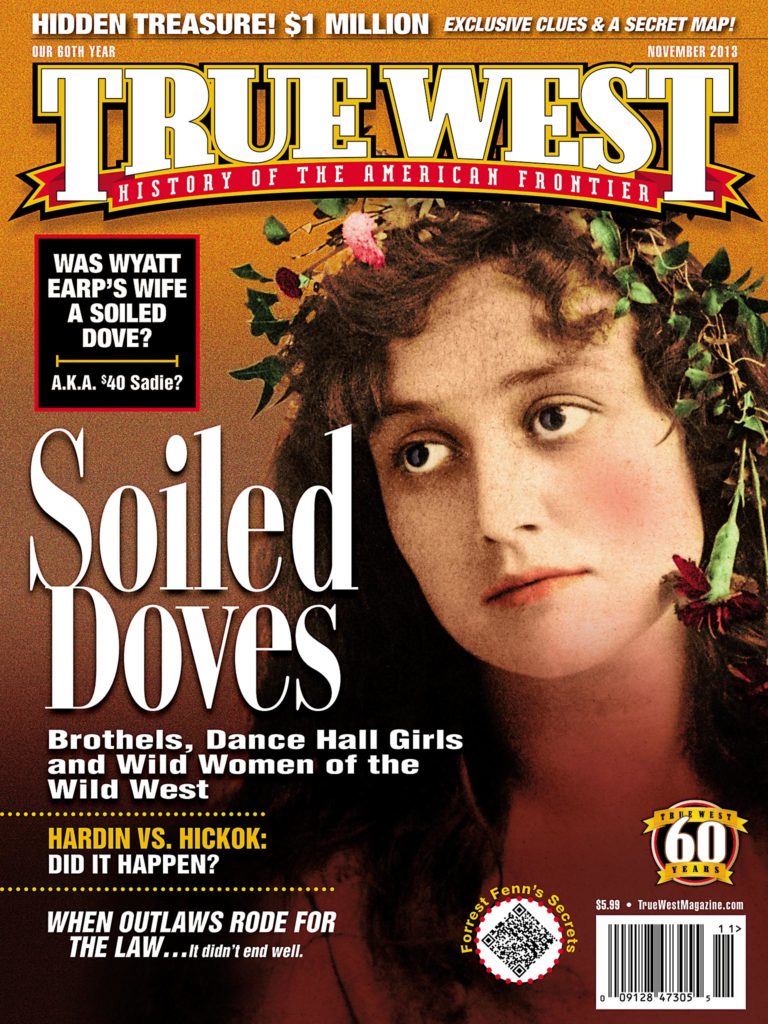

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Craig Fouts Collection –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin Collection –