An “uninhabitable wasteland.”

An “uninhabitable wasteland.”

That’s what Army explorer R.B. Marcy called the wilds of west Texas.

Most folks took the captain at his word and avoided the area. But a few hardy souls, adventurers like Charles Goodnight, C.C. Slaughter and Burk Burnett, saw some business opportunities in the region. Here was a place to fatten cattle on the grasslands of the plains, to prepare the herds for the journeys north and sales in the Kansas cowtowns.

Here was a place for a man to carve out his own world. And all he had to do—other than keep the Indians at bay—was build something from nothing. In fact, many started by digging shelters out of the ground itself. From those humble beginnings came empires that would last for decades.

Flash ahead to today, when the National Ranching Heritage Center works to preserve the history of those who brought civilization to the wasteland. The 30-acre museum and historical park in Lubbock, Texas, holds the real-life history of people who settled the West and left their homes, schools and ranches as proof.

Established to preserve the history of ranching and pioneer life in North America, the Heritage Center houses more than 38 structures, including a depot, train, bunkhouse, one-room schoolhouse, dugouts, windmills, ranch offices and homes. Relocated from prominent ranches, these buildings reflect life from the 1780s through 1930s, and each one is furnished or outfitted to represent its heyday. The stories of the trailblazers and ranching pioneers behind these buildings are reflected in the book Across Time & Territory: A Walk Through the National Ranching Heritage Center.

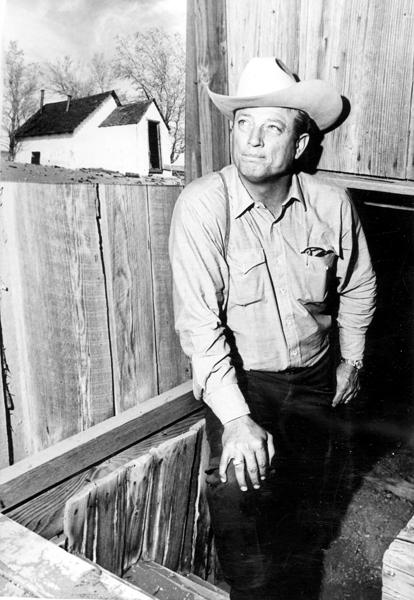

Stepping inside their structures allows visitors to imagine what it must have been like to live in a dugout or bunkhouse, or to learn the three R’s in a one-room schoolhouse. As actor/rancher Barry Corbin puts it, “When you walk into the National Ranching Heritage Center, you step back in time to a simpler, more direct way of doing things. The buildings are authentic; they’re buildings that people lived in. It’s an almost mystical experience.”

For instance, when entering the 1888 Matador Half Dugout, you’re stepping into a world where ranch management wouldn’t allow games of chance among their cowhands in an effort to avoid violence. One of the worst arguments at the Matador stemmed not from a disputed poker hand but from a poorly sung song. One cowboy asked another how he liked his singing of “Yankee Doodle.” On being told how bad a singer he was, the cowboy shot his critic, who shot back. Both men died.

Preserving the story

The NRHC came about through the work of committee members, who in 1966, began locating ranch structures to tell the story of Western development. Owners of the ranches on which the buildings were located made the structures available to the Heritage Center, with others donating funds for the move and restoration. Some buildings were brought to the NRHC on the backs of flatbed trucks, while some were dismantled stone by stone, using meticulous archaeological methods, and then rebuilt in the historical park.

Maintaining this legacy remains the focus of the Ranching Heritage Association today. It strives to keep alive and perpetuate the traditions, intrinsic values and authentic history of the ranching industry. Ranches represented at the NRHC include the King, Slaughter, U Lazy S, Masterson, JA, 6666, Pitchfork, XIT, Matador, Spur, Waggoner, Renderbrook-Spade and others.

“The National Ranching Heritage Center will be around as long as people embrace the values that helped build this country, helped build the West,” says author Byron Price. “All you have to do is walk past the buildings and see the brands XIT, 6666, JA and the others represented there to know the heritage that is embodied in those structures. They tell a great story.”

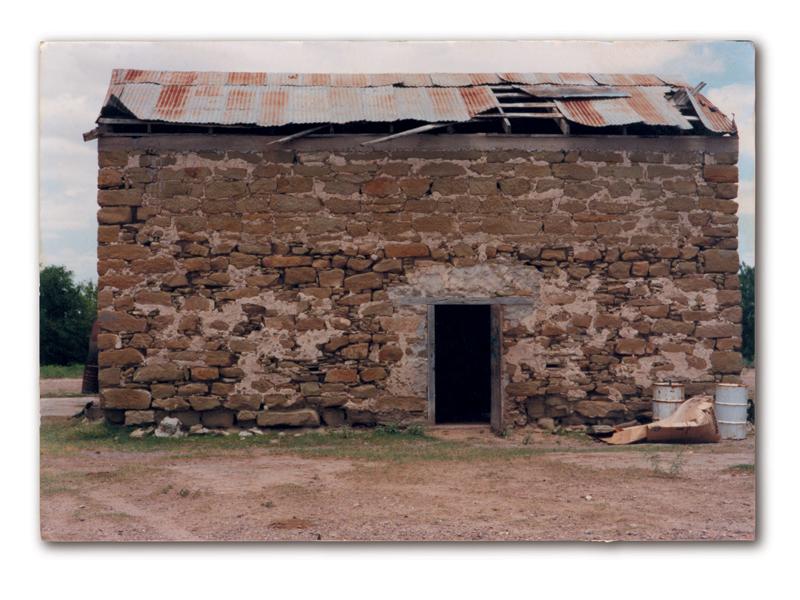

Jowell House, 1872-73

Life on an early ranch wasn’t always what the movies make it out to be, as the story of Mrs. George Jowell relates. When her husband was away on a cattle drive, Indians burned out the family’s cabin. Mrs. Jowell and her baby, with a hired hand, escaped, riding hard, to a neighbor’s home. The Jowells then rebuilt their home, this time of river rock and limestone, materials that wouldn’t be harmed by an Indian attack. The last owner of the house was rancher L.E. Seaman, whose heirs donated the house in his memory. All 90 tons of the hand-cut limestone and sandstone were tagged before they were disassembled for the move to assure accurate restoration.

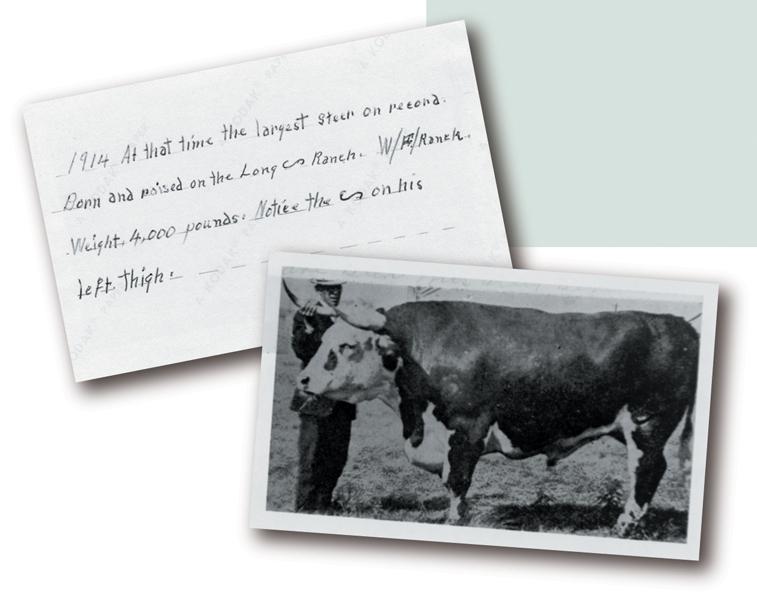

Long S Whiteface Camp 1901, 1905

C.C. Slaughter (named after Christopher Columbus) built a ranch, which, at one time, was second in size only to the famous XIT. He got his start when, in 1897, he purchased 2,000 head of Herefords from rancher Charles Goodnight and kept his cattle on Fountain Goodlet Oxsheer’s Diamond Ranch in Hockley County. He soon purchased that ranch, and in 1901, he and his son George built the line camp, which was a hole shoveled out of the plains and covered with brush.

In 1905, a box-and-strip upper story was added for extra living quarters. When the original structure was moved, only the upstairs went, as the bottom was a hole in the ground. A new basement was dug, though, and lined with concrete blocks to keep out the critters that usually would have found their way in.

Nelle DeLoache Davidson and her brother James DeLoache cut a rawhide thong to officially open the unique, two-story Long S Whiteface Camp. The DeLoache family donated the structure to the NRHC for restoration and preservation. More than 1,200 visitors toured the dugout after its dedication on October 19, 1971.

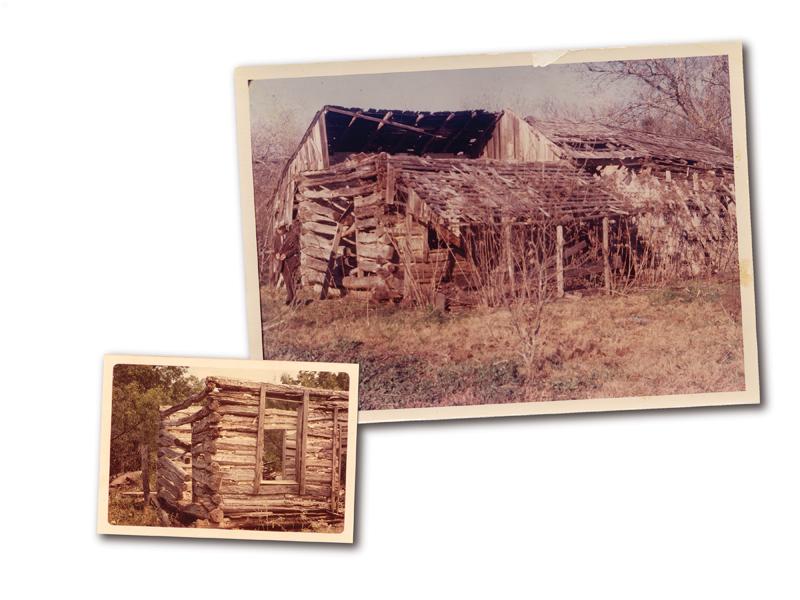

El Capote Cabin, c. 1838

Although the original builder of El Capote cabin is unknown, the history of those who have owned the land where the rustic dwelling was originally built begins with José de la Baume, a French captain in the American Revolution. The land eventually was sold to an investment syndicate, of which Edith Kermit Carow was a member. She married Theodore Roosevelt on December 2, 1886. The Roosevelts never resided on the property, but they conveyed it to Edith’s sister and her husband. The Moores gave Teddy two horses to take to Cuba during the Spanish-American War, which gave rise to the popular saying: “Roosevelt rode a horse from El Capote to the presidency.” The property was later sold to Judge Leroy Gilbert Denman, an associate justice of the Texas Supreme Court. His grandson, Gilbert, made a gift of the cabin to the NRHC, and it was dedicated on October 26, 1975.

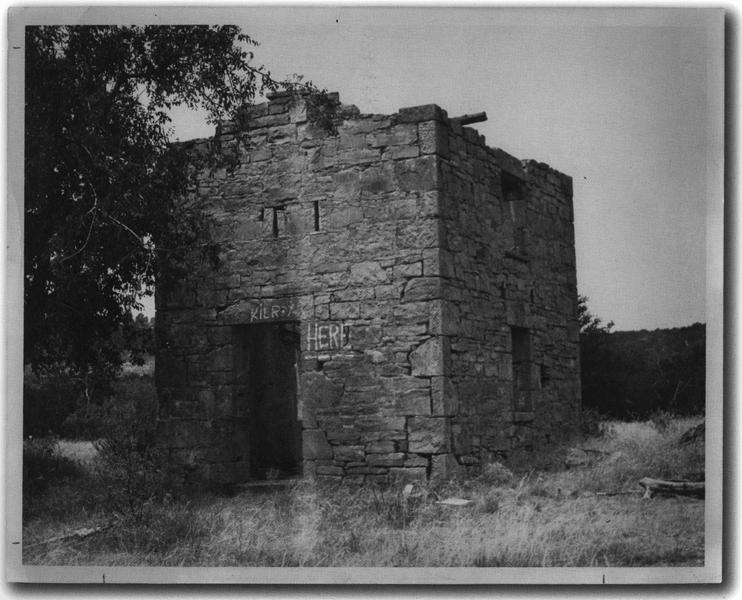

Los Corralitos, c. 1780

John F. Lott, a founding member of the NRHC and grandson of rancher John B. Slaughter, stands beside the construction of Los Corralitos in 1999 (right). Los Corralitos is the only structure at the Heritage Center that isn’t the real thing. When building selection committee members were examining the old compound for moving, they learned that members of the original owners’ family were buried beneath the floor. With that knowledge, the committee decided to construct a reproduction of the fortified house for interpretation at the NRHC rather than destroy the sepulcher.

Don José Fernando Vidaurri built Los Corralitos, or the Little Corrals, which is a single-room dwelling of sandstone, mud, mortar, mesquite and Montezuma cypress. Its walls were 33 inches thick, and instead of windows, it had six gun ports. The roof was also built inside a parapet, or wall, behind which the family could crouch and return gunfire. When the Indian raids eventually subsided, the family built another home and moved next door. But they kept the fort for protection when needed. The replica was dedicated on September 9, 1999.

Photo Gallery

Some believe that after the fall of the Alamo, Santa Anna’s army camped near El Capote Cabin the Saturday before Easter in 1836, waiting for the flooded Guadalupe River to recede. Most historians, however, believe the army camped 20 miles away.

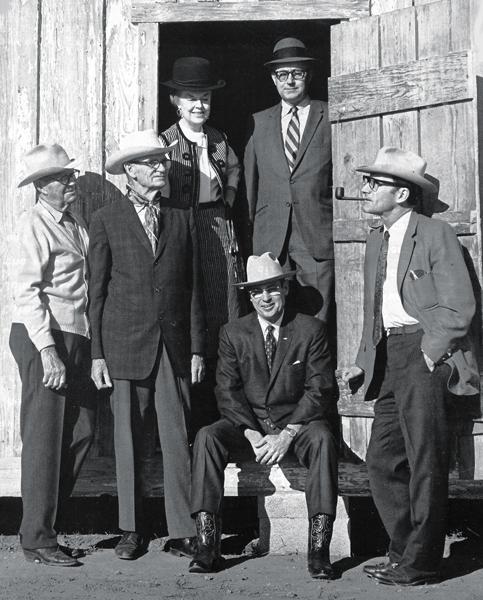

The first officers of the Ranching Heritage Association were (from left, standing) Chairman of the Board D. Burns of the Pitchfork Ranch near Guthrie, Texas; Board President Dr. W.C. Holden, ranch historian; Secretary Frances Holden; Treasurer Robert L. Snyder, an executive with Bryant Radio and Television; Vice President Frank H. Chappell Jr. of the Renderbrook-Spade and Chappell-Spade ranches of Texas and New Mexico; and (seated) Vice President John F. Lott of the U Lazy S Ranch in Texas.