CO-EDITED BY JOSEPH G.ROSA & THADD M.TURNER

CO-EDITED BY JOSEPH G.ROSA & THADD M.TURNER

Even in his own time, they called him “Wild Bill.” And, though this August marks the 125th anniversary of his murder, Wild Bill Hickok is ever immortal. As Thadd Turner and I are both devoted to separating the myth from the fact about his legend, it is fitting that True West— also dedicated to presenting the truth about the Old West—should mark the event.

A fan of the magazine since the 1950s, and having spent more years than I care to remember researching and writing about Wild Bill, I was delighted when Thadd and Bob Boze Bell asked me to guest edit this special issue.

Like all larger-than-life individuals, Hickok was the kind of man who inspired adulation in some and aroused bitterness and resentment in others. In short, he was an enigma, which is one reason why I have pursued the truth about him for so long. Wild Bill deserved his reputation, but not the media-inspired “man-killer” role for which most people remember him—his killings were in single figures, and at times, he showed a compassion that was rare among gunfighters.

James Butler Hickok fought diligently for the Union Army, scouted the open plains for Custer, and provided necessary law enforcement to Hays City and Abilene. Hickok was an actor, media personality, and had killed men. He never slept with Calamity Jane, and was a happily married man on the day he was assassinated.

I, therefore, hope that the readers of True West will find much profit and entertainment in our presentation of Wild Bill Hickok, the legend and the man.

— Joseph G. Rosa

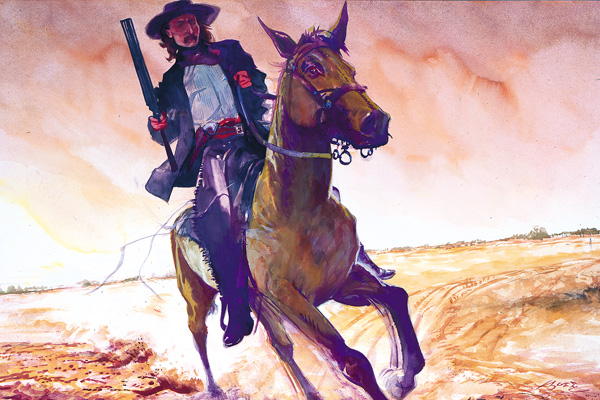

“Wild declared General George Armstrong Custer in 1872, “was a Plainsman in every sense of the word, yet unlike any other of his class.” And where most of his contemporaries were dressed in keeping with the terrain over which they operated, Wild Bill blended “the immaculate neatness of the dandy with the extravagant taste and style of the frontiersman,” which befitted the man Custer regarded as “the most famous scout of the Plains.”

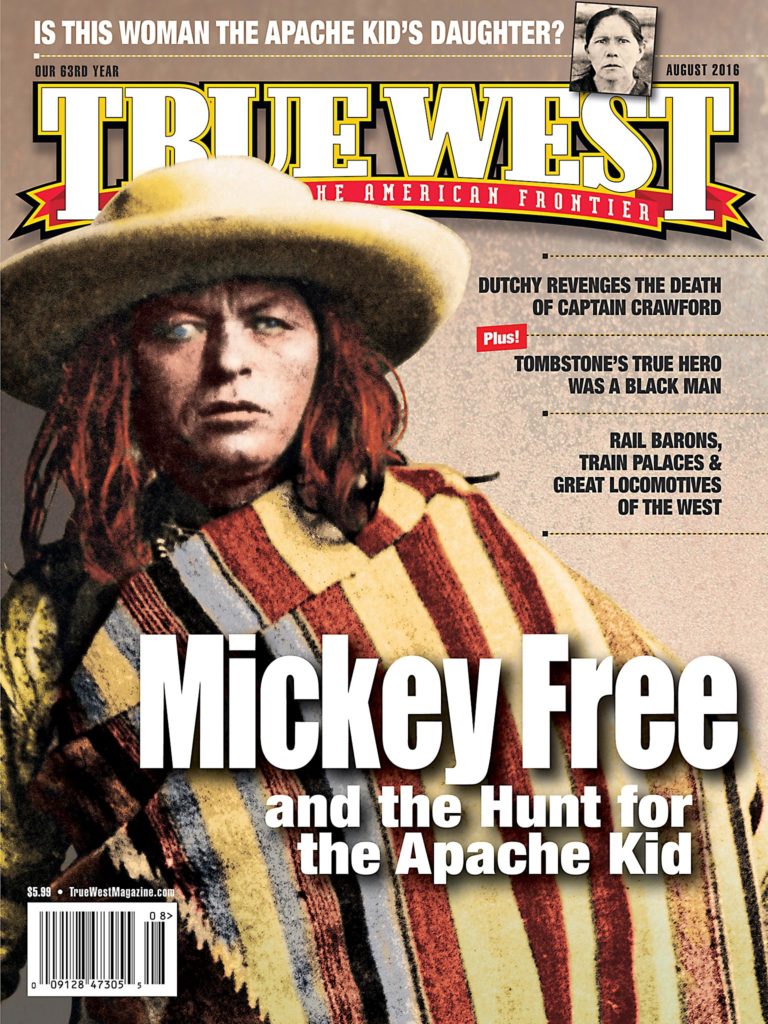

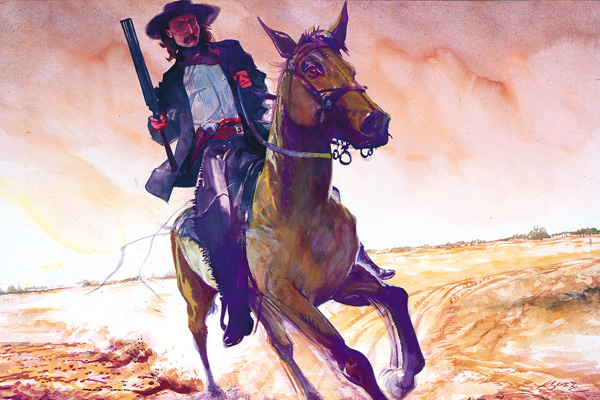

Even when divested of his plainsman’s furs and buckskins, Hickok’s garb remained dandified: colored vests or waistcoats, fashionable jackets with broad lapels, and boiled white shirts with cravat or tie; his high-heeled boots were worn with the tops inside his trousers; the whole was surmounted by a broad-brimmed flat-crowned white or black sombrero-type hat. In his later years, Hickok also sported a fashionable cane. At such times, of course, his pistols were tactfully kept out of sight. However, when employed in peace-keeping duties in such places as Hays City or Abilene, his dandified image gave way to more practical dress and, during the summer months, he was often seen wandering around in shirt sleeves with his two holstered Colt Navy pistols, butts forward, prominently displayed.

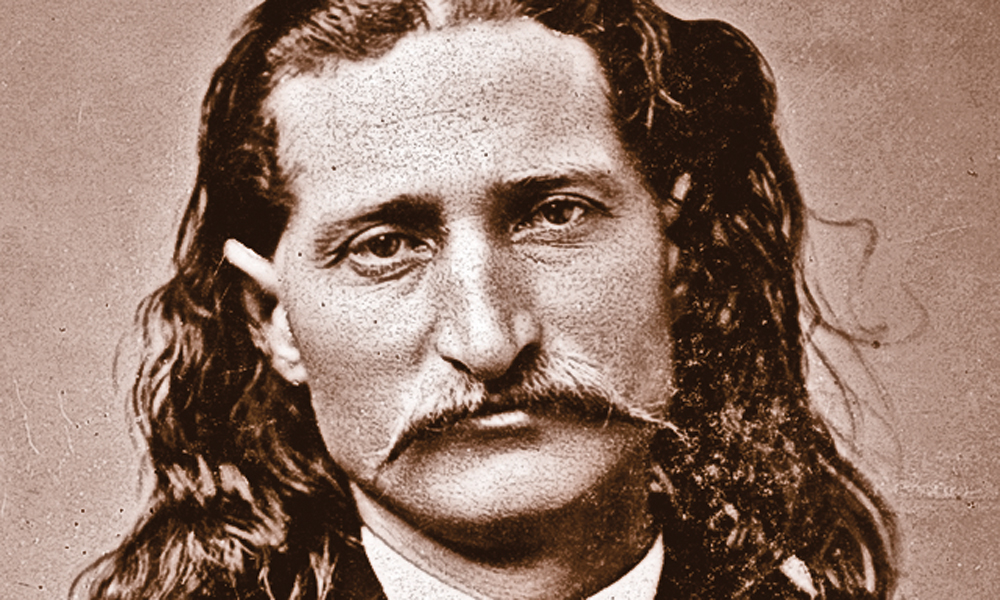

James Butler Hickok’s physical appearance and bearing was eagerly seized upon in an article published in the February 1867 Harper’s New Monthly Magazine by Colonel George Ward Nichols and the Welsh-born Henry M. Stanley (who, in a couple of years, would immortalize himself with the greeting, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”). Photographic and written descriptions of Wild Bill indicate that he stood over six feet tall, was broad shouldered, narrow waisted and wore his auburn hair shoulder length in the manner of the plainsmen. Curiously, his moustache was straw-colored, its length dictated by fashion. His features, too, were distinctive: a broad forehead, high cheekbones, aquiline nose, strong chin and long jawbones; all dominated by a pair of blue-gray eyes that in normal discourse were benign and friendly, though when he was aroused by danger became coldly implacable.

Wild Bill’s reputation as a gunfighter naturally included his ability to get a pistol into action “as quick as thought,” but in reality, speed was probably the last thing on his mind. Hickok told Colonel Nichols that one should take time and not be hurried, which meant that reaction to a situation counted far more than speed—when Hickok went for his pistols he had already anticipated the outcome.

If we ignore Hickok’s leg-pulling, his elevation from noted scout and plainsman to the most notorious man-killer on the border remains a mystery. A cursory examination discloses that he did not deserve such a reputation. Between 1861 and 1871—the period which covers his pistol-wielding ventures—there are only seven authenticated killings involving Hickok. He may (or may not), have shot David C. McCanles at Rock Creek in July 1861, yet it was four years later in July 1865 that he shot it out with Dave Tutt at Springfield. There was then another gap until August 1869 when as acting sheriff of Ellis County, Kansas, he shot and killed Bill Mulvey (or Mulrey) and Samuel Strawhun in September. Ten months later in July 1870, again at Hays, he shot two Seventh Cavalry Troopers in a saloon brawl, killing one and wounding the other. And finally, in October 1871, at Abilene, when attempting to deal with a large band of drunken Texas cowboys, he shot Phil Coe and also his own friend Mike Williams who stepped into the line of fire—a far cry from the “considerably over a hundred” so-called bad men Hickok is said to have killed.

In hindsight, however, it is understandable why such outrageous stories were not denied, especially when Hickok himself rarely gave interviews. Few people got to know the real man or any facts about him, and it is only by examining comments from those who actually knew Hickok, and his own rare letters to the press, that we can get some idea of his true character. From these excursions we learn that he enjoyed books, feminine company, good conversation and socializing. He also displayed a good knowledge of the West, and he was considered an expert on the guerrilla warfare that had pervaded parts of Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas during the late war.

Following his appearance in Harper’s, Hickok, along with a number of other plainsmen, was hired to scout for the Seventh Cavalry, sent into action against hostile Indians in Kansas in the spring and summer of 1867. Hickok soon achieved a reputation as an Indian scout, but unlike his myth, Wild Bill did not ride a prancing mare called Black Nell. Instead, he rode a fine Army mule which was better than a horse over rough country. Some even thought mules to be the equal of the fleet Indian ponies. Indeed, on one occasion when he ran out of supplies, Custer ordered Hickok to ride by night on a fresh mule to request supply wagons to be sent to his command.

Between military engagements, Hickok served as a deputy U.S. marshal in Kansas, and in 1869 he was elected acting sheriff of Ellis county, making Hays City his headquarters. Later, in 1871, he was appointed marshal of Abilene during its last season as a cowtown. Hickok was not a professional peace officer, but took the job seriously, and some described him as a “terror to evil-doers.”

Wild Bill Hickok is one of America’s foremost frontier folk heroes, but the real man remains controversial. To some he was heroic, and to others an overbearing bully, a braggart and, by others, called a coward—but never to his face. In contradiction to the latter opinion stands the trust placed in him by various army officers, two United States marshals, and the people who employed him as a lawman. Make no mistake, Wild Bill had his faults, but he was also a man of character, integrity, courage and action, and for that he deserves his reputation.

Wild Bill was still in Springfield when, in February 1873, it was reported that he had been murdered by Texans at Fort Dodge. A number of sympathetic obituaries had appeared before Hickok himself announced that reports of his death were premature, but for the benefit of the Kansas City papers he declared: “I am dead!” He also seized the opportunity to take a swipe at Ned Buntline, whose abortive attempts to kill him off with his pen had failed, and “having failed, he is now, so I am told, trying to have it done by some Texans, but he has signally failed so far.”

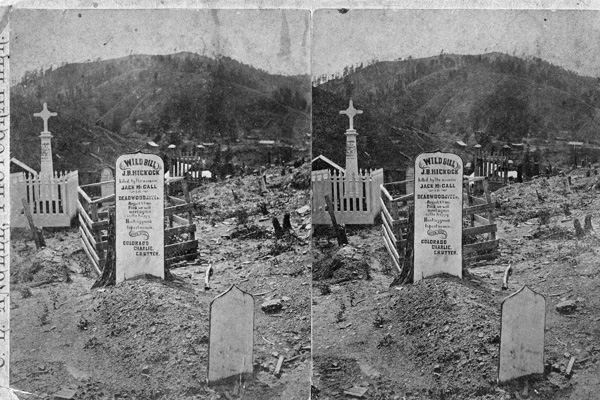

Back in Kansas City in the summer of 1874, Wild Bill resumed his gambling and occasional ventures as a scout and guide for hunters and tourists. Later, he moved to Cheyenne and, over the following 18 months, also spent time in St. Louis. On March 5, 1876, he married Agnes Lake Thatcher in Cheyenne. They first met in 1871 when he was marshal of Abilene and her circus played in town. They kept in touch by mail, and their decision to marry was welcomed by Hickok’s friends and the local press. After a short honeymoon, Hickok left Agnes in Cincinnati with relatives and returned West, promising to send for her when he was settled. Unfortunately, they never met again, for Wild Bill met his untimely death at the hands of back-shooting Jack McCall on the afternoon of Wednesday August 2, 1876.

It will always be, however, his real and imaginary skill with a pistol and his disputed man-killing reputation that will be best remembered. That he was an excellent pistol shot is no longer in doubt, though one could be forgiven for doubting some of the “miraculous” feats that defy man and weapon. Yet they form a part of the legend of a man who, despite his faults and weaknesses, stood head and shoulders above many of his contemporaries, and displayed a strength of character that set him apart. Many men swore to kill him, some with a real or imagined grievance, and others seeking a cheap reputation as his killer. Few of them would dare meet him face-to-face. While they are now obscure and long forgotten, Wild Bill Hickok in all his guises, as both hero and a frontier icon, remains.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming –