No Longer Just About Yesteryear

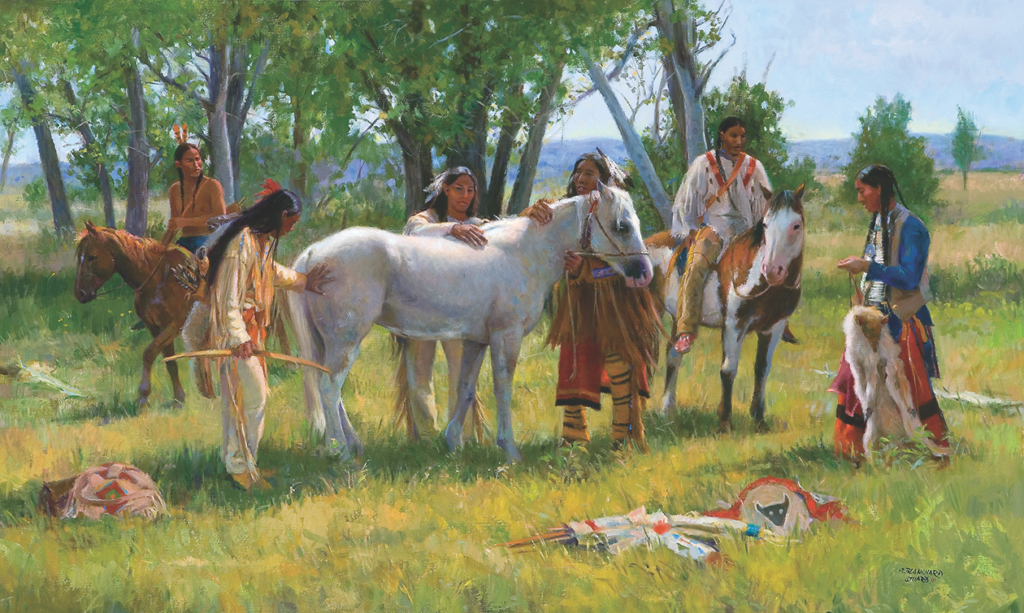

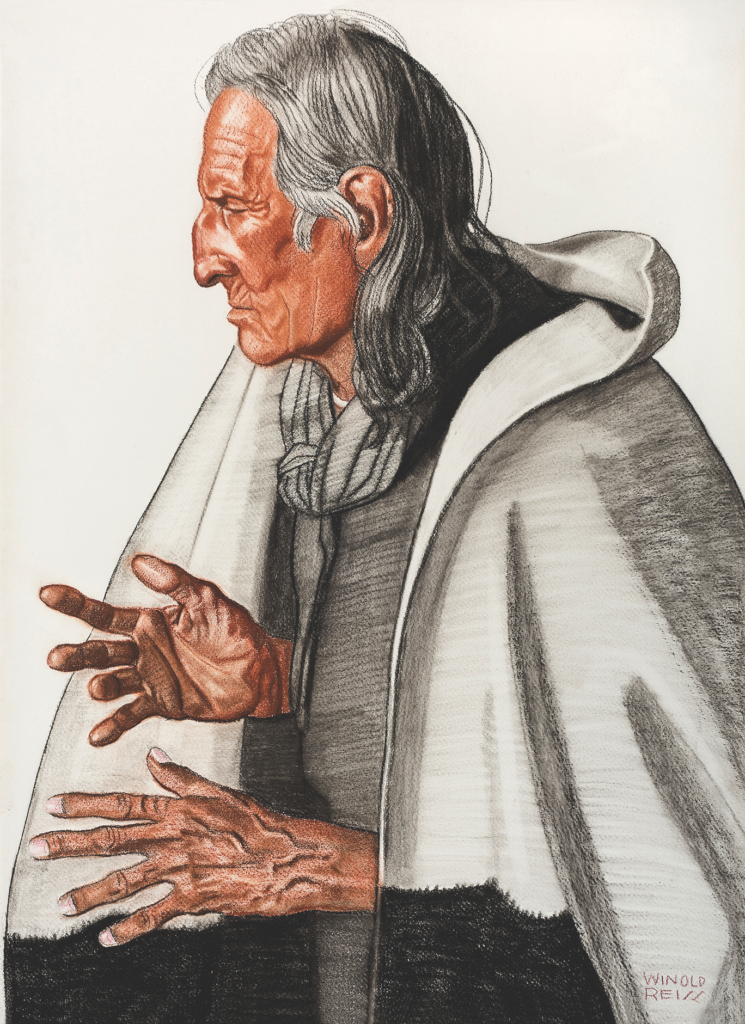

In the 19th century, art of the American Indian was usually viewed through the canvas and brush of White Americans. Think George Catlin, the Pennsylvania-born lawyer turned self-taught painter whose trips West produced some 500 portraits, landscapes and other depictions, not to mention artifacts, that he eventually showed in America and Europe.

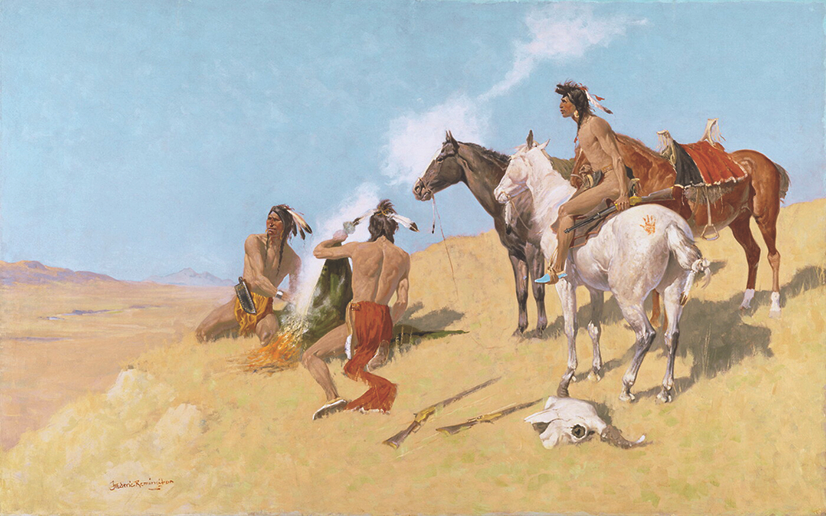

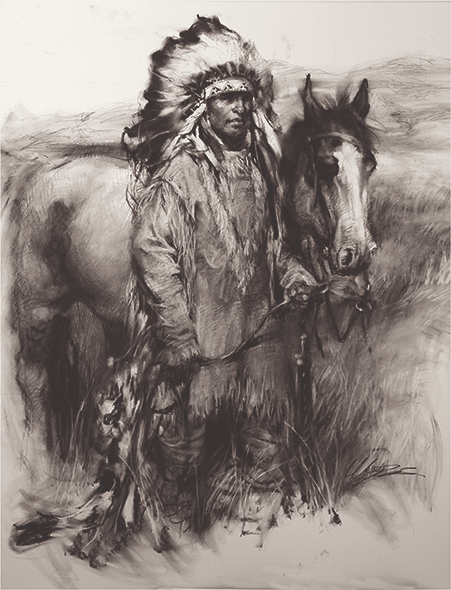

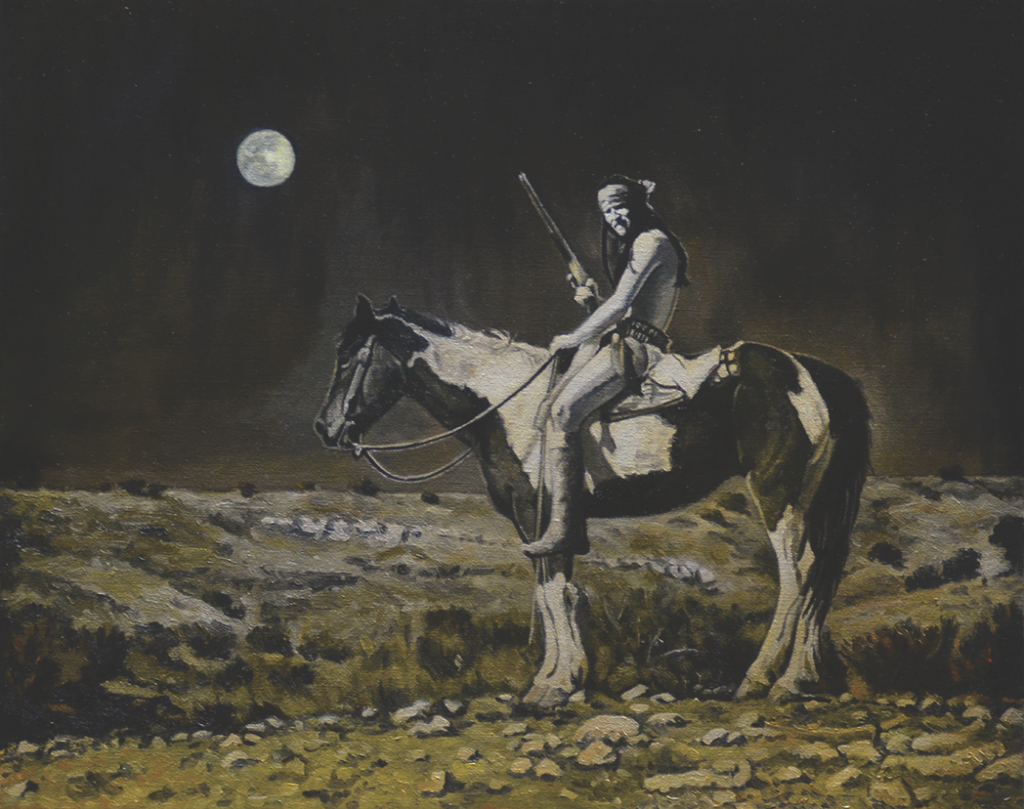

Or Frederic Remington’s Sioux Chief or Captured, both part of the Sid Richardson Museum’s permanent collection in Fort Worth, Texas. Or famed “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell’s 1912 masterpiece Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flatheads in Ross Hole, 4 September 1805, which hangs in the House of Representatives chamber in the Montana State Capitol.

Fast-forward into the early 20th century, when Navajo (Diné) rugs and kachina dolls (though kachinas originated with the Hopis) were the rage; into the 1970s with the boom of the contemporary “Southwest pop” movement; to the rise in attendance at Native American Indian art shows in the 1990s. Santa Fe (New Mexico) Indian Market dates to 1922, but others came along, including Phoenix’s Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market (1958, becoming a juried show 10 years later) and Indianapolis’s Eiteljorg Indian Market and Festival (1993).

And today?

“I wouldn’t pretend to understand the art market,” historical painter Andy Thomas says from his Carthage, Missouri, studio. “After 30 years I seem to know less than ever. However, I think there has been a long-running progression toward depictions of specific tribal groups and away from a generalized American Indian.

“There are many truly talented Native American artists active today. I think we could see some really interesting works of art.”

We already are.

Santa Fe-based Comanche artist Nocona Burgess, known for his vibrant, modern takes on Native (not just Comanche) men, women and culture, never loses sight of his history and heritage (he’s a great-great-grandson of Quanah Parker).

“I think we’re seeing more resurgence,” Burgess says. “[Native] artists are more in control and can dictate what we want to paint, but there’s room for everybody. There will always be room for traditional artists.”

On the other hand, Diné Jerry Brown, known for his abstract takes on Diné culture, points out: “They’re not going to sell my art at a trading post.”

Trading posts typically aim for tourists, but Native art is growing. While there’s still a market for Navajo rugs and Zuni jewelry, contemporary art is making a bold push forward.

“I stay in my own lane,” Brown says, “but push that line. …Through my eyes, I can see stuff that needs to be visited.”

“Always experiment with your work,” Karma Henry, a member of the Fort Independence Community of Paiute Indians, advises today’s Native artists. “That pushes your art and you forward. We are bringing up things happening now and not 100 years ago.”

But new artists aren’t getting all the attention. All-but-forgotten artists from the 19th century are also being rediscovered.

Crow scout Bíilaachia, also known as White Swan, is the subject of a 2022 biography by Rodney G. Thomas: Bíilaachia—White Swan: Crow Warrior, Custer Scout, American Artist from McFarland & Company.

Wounded at the Little Bighorn, Bíilaachia, who scouted part time for the Army until 1881 and died in 1904, created 37 drawings and paintings of his combat history.

“Confined to reservations,” Thomas writes, “no longer allowed to dance and sing, unable to provide for their families as before, forced to learn a language not their own, and with no way to retain a way of life with military skill, the people had few ways to hang onto the customs from the past. There was little they could do to remain ‘the People’ so they resisted in a manner few outsiders understood—they drew. They were the original American artists. White Swan was one of the best.”

In Oklahoma City, the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum recently updated its Native American Gallery. “It was not apparent to our average guest that we were highlighting the regional and cultural diversity of the U.S. West,” says Eric D. Singleton, the museum’s curator of ethnology. “It was there, but most people didn’t recognize the differences in material culture items.”

Brighter paint, lighting and a new layout fixed that. The gallery also incorporates contemporary elements in its exhibits.

“It was critical for us to juxtapose old and new—especially in a space dedicated to Native American cultures,” Singleton says. “Showing our visitors that Native American cultures are not living in the past, but remain vibrant, innovative and ever-changing is a story we are committed to telling. This is a story that should not be limited to our institution either. The story of cultural continuation is the story of humanity and a great way to contextualize history.”

One of the most popular additions to the gallery, Singleton says, illustrates that: “…a beaded Darth Vader helmet by Huichol artist Álvaro Ortiz López-Puwari. Adults and children alike gravitate to it. It is something they know and can connect with. We then use it to highlight contemporary artistry and to talk about the history of bead and quill work by Native American artists.”

Interest in Native art isn’t just rising in the West. Mark Sublette, president of Tucson’s Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery, points to New York’s Whitney Museum of Art exhibition featuring Jaune Quick-To-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation that closed August 13, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s “Grounded in Clay,” which reviews Pueblo pottery from the 11th century to the present day and runs through June 4, 2024.

“This is the first time in the Met’s history to have a first community-curated exhibit of Native American work,” Sublette says. “High-profile, groundbreaking museum art exhibits are spilling over into the Native art market, heightening prices with Quick-To-See Smith’s work having multiple auction sales of over $500,000.”

That’s not new in the West. For more than 35 years, Medicine Man Gallery has specialized in Native arts, displaying them alongside historical Western and contemporary works.

“It’s nice to see the East Coast joining the West in supporting Native art,” Sublette says.

Art of the American Indian can be found across the nation today, from classic and contemporary takes at The Brinton Museum in Big Horn, Wyoming, to the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, and the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and in galleries like Legacy Gallery (Scottsdale, Arizona), Montana Trails Gallery (Bozeman, Montana), Cisco’s Gallery (Coeur d’Alene, Idaho) and The Plainsmen Gallery in Dunedin, Florida.

Even internationally known Prairie Edge—part Lakota trading post, part art gallery in downtown Rapid City, South Dakota, founded in the early 1980s by the late Ray Hillenbrand—is championing new artists with new takes on traditional Native art.

“We have many up-and-coming artists now,” general manager Dan Tribby says, adding that there’s room for traditional and contemporary art. And that room keeps growing.

“It has to be that way,” he says. “Young people aren’t going to go for just the same old way. But the future is bright. It’s really, really good right now.”

It might be contemporary or historical, abstract or photorealism, done by Native or White artists. But it’s all art.

“It’s all storytelling,” Burgess says. “That’s what artists do.”

Michael Roche – American Sculptor

Sculptor Michael Roche loves the history and the people of the American West and it is reflected in his highly collectible sculptures of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday and Crazy Horse. Roche, who works from his studio in Des Plaines, Illinois, has most recently been commissioned to create a statue of Deputy U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves for an award for the U.S. Marshals Service. A student of Frederic Remington and Norman Rockwell’s art, Roche is dedicated to his craft and is inspired to bring real people to life through his art.

For more information on the Illinois artist, go to rochesculpture.shop.

All Photos by Michael Parrish, Courtesy Michael Roche

The Phippen Museum

From October 7, 2023 to February 18, 2024, the Phippen Museum of Prescott, Arizona, will exhibit “East Meets West” in the Marley Gallery, featuring the art of Chinese artist Wei Tai.

Wei Tai Art Courtesy The Phippen Museum

by JaNeil Anderson

Courtesy The Phippen Museum