They say there’s honor among thieves. That may or not be so.

They say there’s honor among thieves. That may or not be so.

But Walker Hammond and Michael Colleran learned the hard way that there are outlaw rules one just doesn’t break.

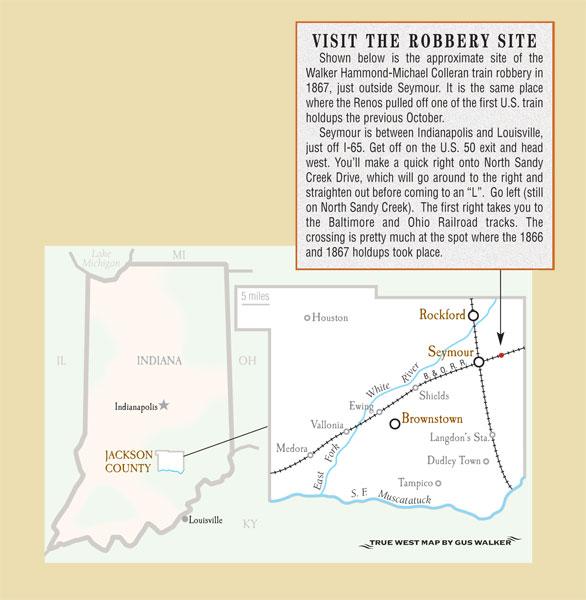

Let’s go back to the mid-19th century in southern Indiana. A family named Reno lived on a medium-sized farm in northern Jackson County—but they were looking to move up in the world. They started off by torching the nearby town of Rockford twice in the 1850s. And when the townsfolk all moved out, the Renos bought the property for next to nothing.

There were five Reno boys: Frank, John and Simeon were hardcore criminals; baby brother William may or may not have taken the outlaw trail; and Clint, sometimes called “Honest Reno,” stayed away from his brothers’ activities. The bad ’uns built up a pretty sophisticated crime operation that delved into burglary, robbery, extortion, bribery, arson, illegal gambling, liquor manufacturing and distribution, counterfeiting and murder. They linked up with hardcases throughout the Midwest to extend the gang’s reach into several states. And from their farm outside Rockford, as well as from their hangouts in the new town of Seymour, the Renos ran the county.

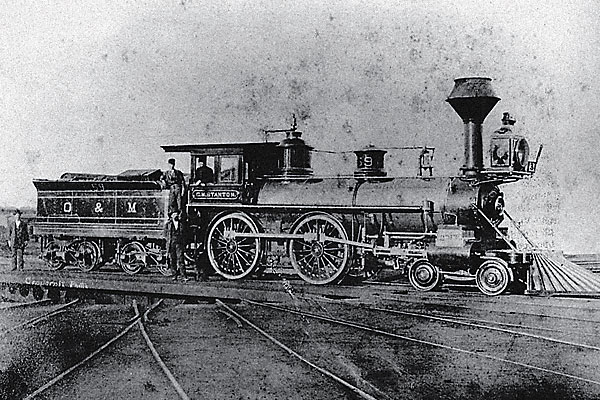

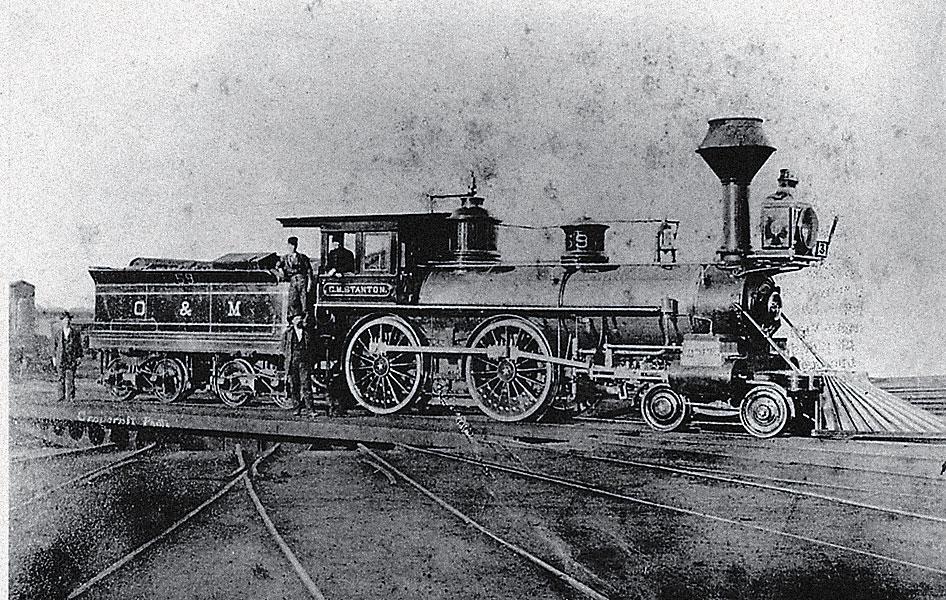

In October 1866, the gang made national news when it robbed an Adams Express money shipment on the Ohio & Mississippi train just east of Seymour. They came away with about $10,000 in one of the first train stickups in U.S. history. And they set an example for dozens of other outlaws throughout the country.

Including some locals.

Enter Michael Colleran and Walker Hammond. Colleran was a teenager from Seymour who apparently sold newspapers on the train. Hammond was described as a middle-aged recluse from Rockford.

Just how they were associated with the Reno Gang isn’t clear. But it’s generally believed that they were at least hangers-on, guys who liked to be seen with the infamous Renos. Another thing that’s not clear—just what the real gang members thought of Colleran and Hammond.

But the two apparently were impressed with that first train robbery—so impressed that they decided to try it themselves. On the exact same train, at the exact same site, in the exact same way that the first holdup went down.

Copycats Beware

As the O&M train left Seymour in the early evening of September 28, 1867, the two jumped on board and made their way to the Adams Express car. They knocked out the express messenger, who had about $8,000 on him. The bandits planned to throw the Adams safe out the door so that they could crack it in the privacy and comfort of their own place—but the company had beaten them to the punch by bolting the safe to the floor. Besides, some passengers had seen them climb aboard and guessed what was afoot; they pulled the emergency cord, and the engineer stopped the train. So Colleran and Hammond jumped off and headed back to Seymour, where they found a place to lay low until the heat was off.

But they’d made another mistake. The boys didn’t wear masks to hide their faces. Some of the passengers recognized them and told local lawmen who to look for. But the sheriff and his men weren’t alone in the search.

It seems the Renos were miffed, to put it mildly.

And they weren’t about to put up with a couple of upstarts who failed to get clearance to pull off such a job—or at least to share some of the ill-gotten gains from the heist. And because the local law enforcement agencies were incompetent, the gang members decided to take the matter into their own hands.

Sabotage

The Renos didn’t know exactly where the two miscreants were hiding, but they came up with a way to smoke them out. John Reno provided the bait—his girlfriend, who apparently was the subject of Hammond’s dreams and desires. She put out the word that she wanted to hook up with the newly rich robber—in fact, the message suggested that the two just might run off together and live happily ever after.

Walker Hammond bit.

He arranged to meet his fantasy girl in Seymour. His pal Michael Colleran went along (didn’t they know that three’s a crowd?). So they showed up at the designated place at the designated time … and came face to face with the Renos. John and Frank and company proceeded to beat the hell out of the two and to confiscate the loot from the holdup. Then, doing their civic duty, the gang turned Hammond and Colleran over to the Jackson County sheriff, who took the hapless duo to the jail in nearby Brownstown.

A mob wanted justice in the worst way, so they took their ropes and showed up at the jail in search of the boys. The sheriff and his deputies managed to turn them away on multiple occasions through the end of 1867. In February 1868, the two were indicted for the robbery. Colleran decided to plead guilty; Hammond went to trial and was convicted. It didn’t make much difference; young Michael got five years in the state pen at Jeffersonville, while his partner was sentenced to six years in the same facility.

That just might have saved their lives.

Vigilante Power

By that time, John Reno was already behind bars, serving time in Missouri for a burglary of the Daviess County treasury committed in November 1867. But the rest of the Reno Gang continued its ways until the citizens of Jackson County decided enough was enough.

In the summer of 1868, a total of seven gang members were captured by law officers—and strung up by local vigilantes. Frank, William and Simeon Reno, along with pal Charlie Anderson, were arrested and jailed in the Ohio River town of New Albany. That didn’t save them; in December, the vigilantes paid them a visit with several lengths of strong hemp. All four died in an incident that made international news.

Walker Hammond and Michael Colleran were safe in their cells.

Staying on the Outlaw Trail

Colleran got out in 1873. Reportedly, he left the area and went straight, disappearing into the mists of history. Hammond wasn’t that smart. When he was released from prison, he just couldn’t stay out of trouble throughout the 1870s.

By 1885, he was running with a gang based out of Osgood, in the far southeast corner of Indiana. Ironically, some of the members of the outfit had run with the Renos some 20 years earlier. And they’d picked up at least one notable—Henry Underwood, who rode with fellow Hoosier Sam Bass in Texas in the 1870s. After Bass died in a shoot-out in Round Rock, Underwood high-tailed it back to his native state—but stayed on the outlaw trail. Apparently, he and Hammond partnered on some burglary jobs.

Underwood was captured in November 1886. Hammond stayed on the lam for another three months before he was run to ground. In February 1887, he was tried for looting a hardware store. The law’s patience had run out; Hammond was sentenced to an astoundingly long 13-year term in the state prison at Michigan City. He didn’t serve the entire time, though. By 1889, he was showing signs of cancer—a near certain death sentence unto itself. He petitioned for a humanitarian release so that he could die outside of prison, but his request was denied. In early 1890, Hammond cashed in his chips.

History hasn’t been kind to Walker Hammond and Michael Colleran. The Renos are remembered as criminal innovators who went down bloody. Hammond and Colleran? They’re a couple of sad sacks who ran afoul of their pals because they ignored basic outlaw rules: always ask permission of the top dogs, and offer to share the loot with the big boys.

Photo Gallery

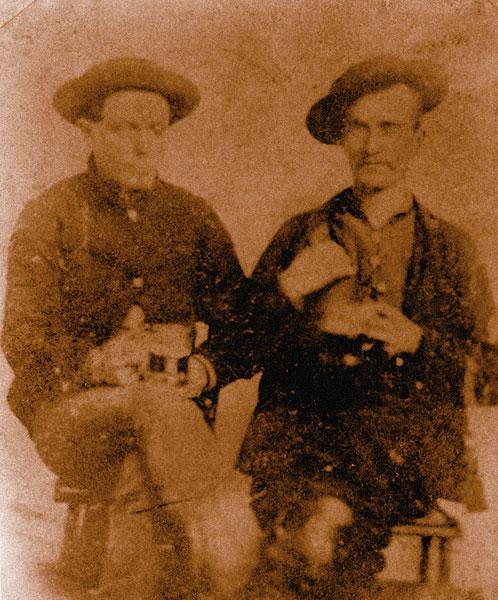

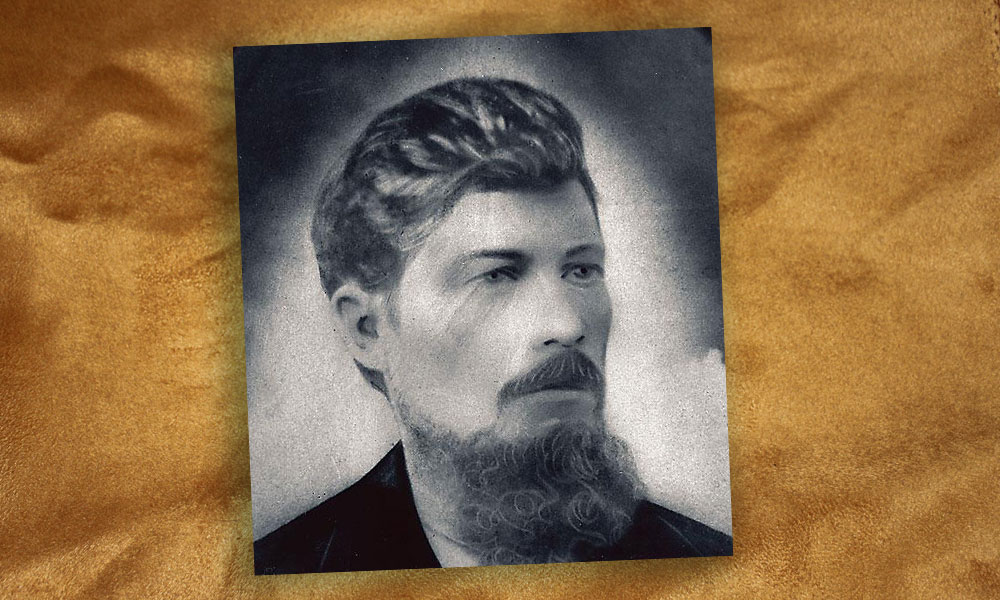

John Reno and gang member Frank Sparks, 1867. This photo was probably taken in a Seymour, Indiana, saloon (note the beer mugs in their hands) by tavern keeper Dick Winscott—who was working undercover for the Adams Express Company.

– All photos courtesy Mark Boardman Collection –