The Western novel became a reality around the turn of the 20th century. But no one else stamped the Western bookshelf as much as the Ohio baseball player and dentist Zane Grey did with his brand of Westerns.

The Western novel became a reality around the turn of the 20th century. But no one else stamped the Western bookshelf as much as the Ohio baseball player and dentist Zane Grey did with his brand of Westerns.

Zane’s novels Heritage of the Desert in 1910 and Riders of the Purple Sage in 1912 launched his career as the top selling Western novelist. But all wasn’t that easy for Zane. Riders of the Purple Sage was a controversial novel, which his publisher originally refused to print due to Zane’s references to Mormons as the bad guys. A rift in the West had existed since the 1850s, between non-Mormons and Mormons, over the historical Mountain Meadows Massacre of a large non-Mormon wagon train in southern Utah. Zane’s publisher was concerned the book dealt too deep in this still ongoing issue and would upset many people. Zane threatened to self publish the book himself, but in the end, he won, and the book was a national success. Except in Utah, where rumor had it that the book was not to be sold by the faithful.

Zane wrote novels that by today’s standards are brimful of descriptions of the land. But at the time he wrote them, there were no TVs, no movies, no Life magazines to show people the West, so they were anxious to view, through the author’s eyes, this vast landscape of the frontier. Zane took people to Arizona’s Oak Creek Canyon in his book Call of the Canyon. The pages described a sunset’s glow on the spheres and cliffs that towered over the rushing trout stream. While today’s reader knows this country with only a gentle push by the author, his fans then had never been there before, which is why his books were travelogues as well as stories.

From the Ohio youth who spent his summers camping, fishing and playing baseball came the world hunter and fisherman. A great-great aunt of his on the Ohio frontier inspired his first novel, Betty Zane, which Zane self-published. For several years, every chance he got, he stalked the New York offices looking for a publisher, until he found one.

During his hunting trips to Arizona, where he struck up a friendship with guide “Babe “ Haught, Zane began to gather ideas for his future novels. The Tonto Basin Range War was still on the minds of folks in the Payson, Arizona, area. Many of the participants were still alive when Zane first visited.

Zane was not far off the mark on the actual events that took place there, but Riders of the Purple Sage is marketed as a fictional tale, perhaps as a mild camouflage to suit his editors. The controversial book hit the bookshelves, earning high sales. Even today, Western Writers of America carries this work on its 10 Best Westerns list.

Zane liked Payson so much that he bought three acres from his guide Haught and had him build a cabin for Grey to use when he visited Arizona on hunting trips.

Dolly’s Purple Prose?

A not infrequent comment critics make about Zane’s writing is that his style has a feminine touch, sometimes called purple prose.

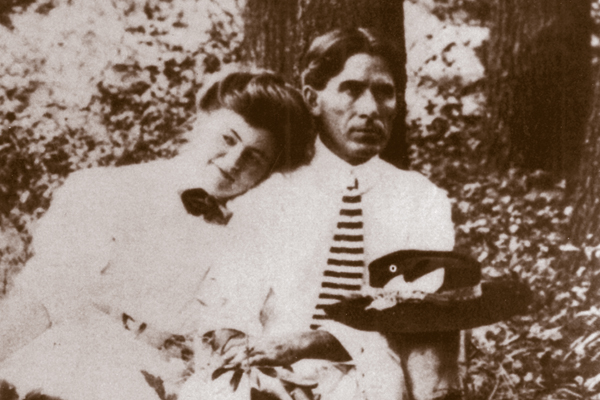

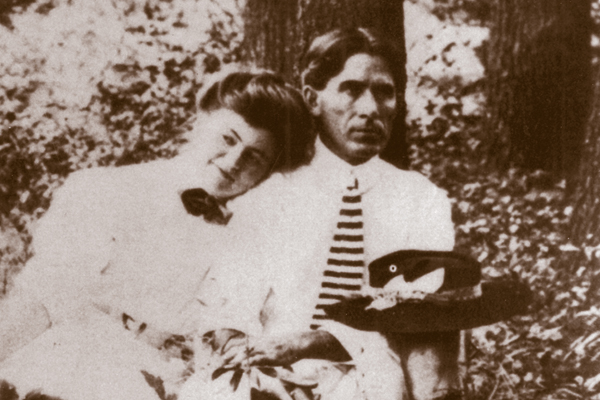

Zane wrote his books in longhand in a three-ring notebook on a desk that fit on the wooden arms of a stuffed cushion leather chair—basically, writing in his lap. When he completed a novel, he gave it to his wife Dolly to transcribe, kissed her goodbye and headed off on another outdoor adventure.

Perhaps he was thinking of Dolly when he wrote in Riders of the Purple Sage: “Love of man for woman—love of woman for man. That’s the nature, the meaning, the best of life itself.” Without Dolly, who knows if he would’ve become the powerhouse he did. After all, Dolly may have been the real writer in the family. Anyone knows most drafts are only that—a raw collection of an idea that needs to be hued, planed and then sanded into legible words for a reader. Creation is but half the task, and editing is always the time consuming, tedious part.

The couple must have argued about scenes and particular parts in the books that they disagreed upon. Letters remain of their conversations, revealing complaints Dolly had with scenes. Zane’s impatient replies were usually: “Then you write it.” So the books, through her editing, naturally took on many of her views and no doubt curbed some of Zane’s masculine abruptness. Written when Victorian modes were fashionable in fiction, she probably culled anything that deviated from that code.

The truth about their partnership emerged while Dolly was away, visiting in England, and Zane’s publishers wanted his promised book. Of course, his book was still in his scrawl in a notebook, but he grew tired of their demands and sent it to them. They couldn’t even read it. When Dolly found out, she wired them to hold the book; she was on her way home, and she would fix it. She did, of course.

Dolly also acted as her husband’s agent. She controlled the money deals with publishers and later, the movie studios. Zane didn’t want to be bothered with the business end, and besides, his wife was a tougher deal maker than he was anyway. Dolly definitely could have been the inspiration for Tammy Wynette’s “Stand by Your Man.”

Zane could also be vain. Author Owen Wister and artist and writer Frederic Remington were college buddies of Teddy Roosevelt, and they were the talk of social columns. Zane had no such contacts in the White House, and he mentioned that he should, since his books had become so famous. In the early 1930s, President Herbert Hoover did invite the Greys for supper with him and his wife. This is at the heights of the depression, unemployment and the rest, while Zane was earning millions. And all he could talk about over the meal was the oppressive four percent federal income tax that was breaking him.

Grey’s Transition Into Movies

The 1920s brought a new media to people: silent movies, which included The Great Train Robbery—a flickering Western filmed in New Jersey that began to delight audiences across the nation to the tune of a tinny piano. Little did anyone know that the number one Western author would soon have a far reaching effect on another industry: Film.

Zane made 10 films of his own, plus he sold the rights of many of his books for Hollywood to adapt to the screen. A majority of these films were made north of Flagstaff in Monument Valley and nearby country. This vast open land, unfit for a cow, would be used in John Ford’s epics.

Zane’s influence on the West, whether through his pen or the big screen, has endeared the writer to many, including myself.

A Promise to Grey’s Ghost

In the 1950s, during my college years at Arizona State University in Tempe, I made a pilgrimage up to Grey’s cabin. Mrs. Winters owned the place then, and I sought her out for permission to go up there and look around. She was a grandmother type with sharp eyes that looked me over in my cowboy attire, and she nodded her approval with an “I don’t let just anyone go up there, but if you think you want to write Western books, go ahead. Something might rub off.”

The cabin was in bad shape by then. It had Texas-ranch style porches, where Zane reportedly sat and wrote his books. Several French doors led to the outside, instead of windows, and must have ventilated the cabin. From that vantage point, I saw across Zane’s beloved Mogollon Rim. I seated myself on the edge of the porch and promised his ghost that I’d join him on the bookshelf. (At this same time in my life, I had also promised Casey Tibbs’ image in Life magazine that I’d outride him someday, too.) So that sunny day a half century ago, when I took this part pilgrimage to the shrine of one of my idols and the rest for trout fishing in Tonto Creek, became indelible in my mind.

When the cabin was restored, it was next on my list of places to return and visit. An issue of Arizona Highways magazine had done a neat spread on it and brought back many memories. Before I could return, however, a forest fire had destroyed the place. Fifteen years later, I may finally get my chance to see it again, as it has been rebuilt by the Zane Grey Cabin Foundation (see sidebar).

Payson has changed a bit since Zane described it as “an old hamlet, retaining many frontier characteristics such as old board and stone houses with high fronts, hitching posts and pumps on sidewalks, and one street so wide that it resembled a Mexican plaza,” adding that the town “contained two stores, where I hoped to buy a rifle, and hoped in vain.” But hunting, fishing and camping remain popular in the Rim Country, at the base of the scenic Mogollon Rim.

Dusty Richards fulfilled his promise to Zane Grey’s ghost and has written over 40 novels. His latest Westerns are his “Dakota Lawman” series.