As the United States commemorates the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, historians have had an opportunity to revisit the legacy and lives of America’s most significant leaders and their roles in shaping American history, North and South, East and West, in the 19th century and beyond.

As the United States commemorates the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, historians have had an opportunity to revisit the legacy and lives of America’s most significant leaders and their roles in shaping American history, North and South, East and West, in the 19th century and beyond.

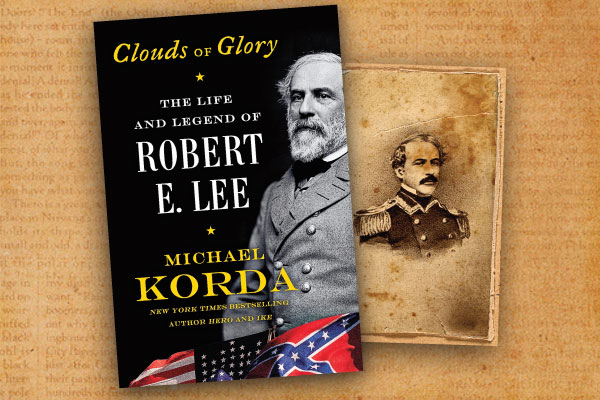

Former editor in chief of Simon & Schuster Michael Korda’s latest biography Clouds of Glory: the Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee (HarperCollins, $40) is a seminal, reexamination of the American hero, and how his family, life and actions as a soldier, leader and educator, before and after the Civil War, significantly contributed to the growth and development of the United States, including the American West. Most significantly, Korda enlightens the reader on the duality of Lee’s life and his inner conflicts: the fact that Lee spent more of his distinguished military career in the West versus the years leading the Confederate army; his dislike of slavery, but opposition to northern abolitionists; his loyalty to family, friends and home state of Virginia, over his Army commission and Constitutional oath. According to Korda’s book, “Lee might have been reluctant to go to war to defend an institution that he disliked and thought the South would be better off without, like most southerners he also believed that the Federal government had no business imposing northerners’ views on the ‘slave states. …’ His opinions, in short, were moderate by the southern standards of his time.”

For historians—and aficionados—of the American West, Korda’s biography of Lee is essential to understanding his role in shaping the history of the Western United States, both before, during and even, after the Civil War. Second in the class of 1829 at West Point, Lee was trained as an engineer, and spent the first five years of his career building forts along the Eastern Seaboard. In 1835, he had his first venture west, assigned by the Army to survey the border between Ohio and the Michigan Territory to settle a feud between the neighbors that had originated in 1787. While not necessarily enamored with the Great Lakes region, Lee’s role in the history of the Midwest and the Mississippi River Valley, and ultimately the Trans-Mississippi West, had just begun. In the spring of 1837, Lee accepted his most important assignment: the engineering of the Mississippi River at St. Louis. Lee did not know it, but his most significant professional work until the Civil War, would be in the West. Following his success in St. Louis, Lee would begin his first of three tours of duty in Texas: first under the command of Gen. Winfield Scott (serving alongside his future opponent, Ulysses S. Grant) in the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848. In 1855, after a tenure as superintendent of West Point, Lee was part of a major Army contingent sent first to Kentucky and Missouri to train troops, and then to Texas to protect the border frontier. His final assignment before the Civil War, which followed his famous capture of John Brown at Harper’s Ferry, was first as commander of the Department of Texas and then as regimental commander at the frontier outpost, Fort Mason. After Texas seceded in February 1861, Lee found himself temporarily a prisoner-of-war, before he was called back by Gen. Scott to take command of the Union forces. His refusal over loyalty to Virginia ended Lee’s service to his nation, but began his actions that would shape his country forever in war and peace.

Extremely well researched, written narratively for a popular audience with detailed endnotes and extensive bibliography, Korda’s biography of Lee should be well-enjoyed by all interested in gaining a greater understanding of one of the most influential leaders in American history, before and after the Civil War, East and West. –Stuart Rosebrook