December 13, 1877

December 13, 1877

At the Texas Ranger com-pound in San Elizario, Texas, Ranger Sgt. C.E. Mortimer walks down to El Molino to check in on the Rangers stationed there.

On his way back to the barracks, a shot rings out from the roof of Nicholas Kohlaus’ store and hits Mortimer in the back. The Ranger runs a few steps but falls. Firing breaks out on both sides as Lt. John B. Tays runs out from the barracks and pulls Mortimer to safety. (Mortimer dies three hours later.)

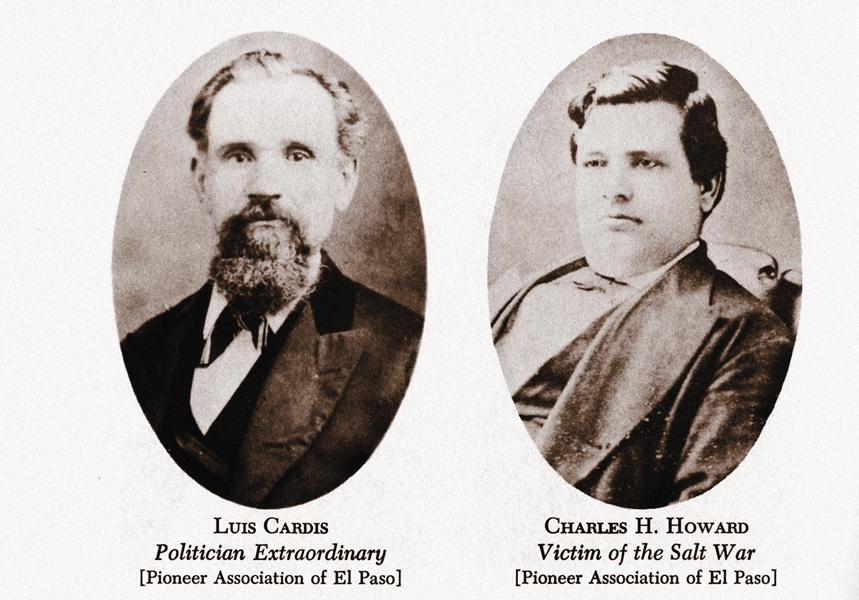

Charles Howard is the target of the shooters. He killed a popular local politician, Louis Cardis, who opposed Howard on ownership of the salt lakes. After agreeing to leave town, never to return, Howard did anyway and is now under the protection of the Rangers.

Tays deploys men on the roof of the barracks, yet they are at a disadvantage as snipers on the roof of Mauro Lujan’s house, 150 yards away, are slightly higher. One shot cuts the rim of merchant John Atkinson’s hat as he hugs the roof; the shot also gives Rocky Mathews a haircut. As the men attempt to cut a hole in the roof, Ranger John Eldridge chops off two of his fingers getting it done.

Several charges are beaten back, although Mathews later testifies, “[I] never saw a man after the first half hour’s firing.”

Two Rangers on the roof of El Molino pick off an insurgent as he raises his sombrero-clad head a little too high.

Around 4 p.m., the insurgents request a truce. Yet when Rangers attempt to retrieve blankets from the roof, insurgents fire at them. Firing continues sporadically throughout the night.

The next morning, insurgents charge the Rangers’ corral but are once again beaten back by bullets. They make eight attempts to broach the Ranger defenses, but the able fighters inside hold them off. Attacks continue into the night, some say three.

The following day, December 15, insurgents try to flood the Ranger position but fail. So they begin tunneling under the headquarters to place explosives.

Mrs. Frank Campbell and her two children cross from the Ellis store (inside El Molino) to the Ranger barracks. Insurgents fire at them, but the three safely cross. She tells Tays the insurgents are breaking through a wall in Atkinson’s store to get to Ranger Capt. Gregorio Garcia’s men.

She asks Tays to leave the door open and have his men cover her husband and fellow Ranger Frank Kent, so they can make a break for the barracks. The men safely cross and report that Capt. Garcia is wounded in the head and leg, and Miguel Garcia is also wounded.

Meanwhile, insurgents have dis-covered store owner Charles Ellis in a wine cellar. They jerk him out into the street and lasso him to a horse. They then drag him out of town where they slit his throat and leave him to bleed to death.

By Sunday, December 16, El Molino has fallen and the Rangers have lost the field of fire. Insurgents now brazenly run right up to the barracks and fire into the Rangers’ own portholes. The Rangers abandon the front rooms and retreat to the rear of the building. As they do, their adversaries spring the “mine” they had dug, but the explosion does only minor damage to the structure.

Around 11 a.m., Tays raises a white flag. Pecos County Deputy Sheriff Andrew Loomis wants to leave. Tays steps outside to parlay with an emissary, who offers a ceasefire until morning, with negotiations to follow. Tays agrees. As the Rangers bed down, they can hear digging.

When they awaken, they discover rifle pits built closer to the barracks. The Rangers prepare to negotiate. Insurgent leader Francisco Barela’s offer: If Howard relinquishes his rights to the salt lakes, they will not hurt him.

Tays presents the terms to Howard, who wearily hangs his head, saying, “I will go, as it is the only chance to save your lives, but they will kill me.”

He is right on both accounts.

Salt War Timeline

AD 800: Indian hunters and gatherers occupy the Guadalupe Salt Basin.

1598: Spaniards arrive at the Pass of the North (El Paso del Norte). The King of Spain grants the salt lakes to the people in common.

1789: Construction begins on San Elizario Presidio.

1848: San Elizario, Socorro and Ysleta become American towns. The people retain ownership of the lakes.

1862: El Paso County’s Tejanos rise up against Sibley’s retreating Confederates.

1866: The Texas State Constitution allows private ownership of mineral deposits. Anglo politicians and capitalists begin years of vicious in-fighting for control of the county and its salt lakes.

Summer 1877: Austin capitalist George B. Zimpelman and his agent, son-in-law Charles Howard, lay claim to the salt lakes and demand that the people pay for their salt.

October 1, 1877: About 200 Tejano insurgents seize Howard and force him to sign away Zimpelman’s salt rights.

October 10: Howard shotguns Louis Cardis, the Tejanos’ political champion.

November 10: Frontier Battalion commander Maj. John B. Jones puts Lt. John B. Tays in charge of a ragtag new Texas Ranger detachment.

December 1: Insurgent leader Leon Granillo defies Howard by leading a wagon train of Tejano salt gatherers to the lakes.

December 12: Howard unwisely returns to San Elizario to press his claim in court.

December 13: More than 600 Tejanos and Mexican citizens under Francisco “Chico” Barela lay siege to the Texas Rangers protecting Howard.

December 17: Howard gives himself up, and the Texas Rangers are also tricked into surrendering.

Acabenlos! (Finish them!)

The Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) who fight at San Elizario successfully overthrow the local govern-ment in El Paso County for 84 days and force the surrender of 20 Texas Rangers. As many as 650 men bore arms, 20 to 30 died and scores more were wounded.

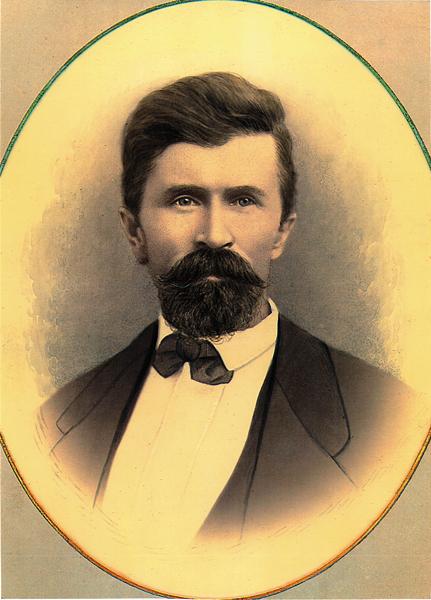

Led by “Chico” Barela, the ragtag insurgency boasts Indian fighters and former Rangers, although most are farmers and vaqueros. They are brave and determined men, but from the Texas Rangers’ point of view, the insurgents are one step above a mob.

Barela tells Lt. Tays that Howard is safe so long as he relinquishes all claims to the salt lakes. Having convinced Howard to surrender, Tays accompanies Howard and Atkinson (who joins them as a translator) to the Gandara home where Barela shrewdly separates the trio. Howard and Tays are held in one room, while Atkinson is isolated and persuaded to fork over the $11,000 of assets he is carrying. He agrees on the condition that he, Howard, McBride and all the Rangers will depart without molestation. Atkinson is also assigned the task of writing out an agreement for the Rangers’ surrender (Tays is in another room and isn’t privy to any of this).

Sent to the Ranger compound, Atkinson tells the Rangers that Lt. Tays has “ordered” them to go down “with [their] arms” as they are “wanted as witnesses, and that all [has] been peaceably settled.”

Using Atkinson as a wedge, Barela has successfully convinced the Rangers at the compound to give up the fight.

Once the Rangers walk out and they are disarmed, the junta leaders decide to execute Howard, Atkinson and McBride. One at a time, the three are walked to a wall near the Borrego building and shot. Atkinson brings up Barela’s promises, but the crowd shouts, “Acabenlos!” (Finish them!). The insurgents hack their bodies to pieces and throw them down an abandoned well.

The gathered crowd is not satisfied and begins demanding the lives of all anglos. To his credit, Barela convincingly threatens them with bodily harm, and they desist. But even Barela can’t stop the subsequent looting, which spreads to even the stores of Tejanos who support the insurgency.

In the end, Chico Barela rises to leadership in a crisis, then fades into obscurity.

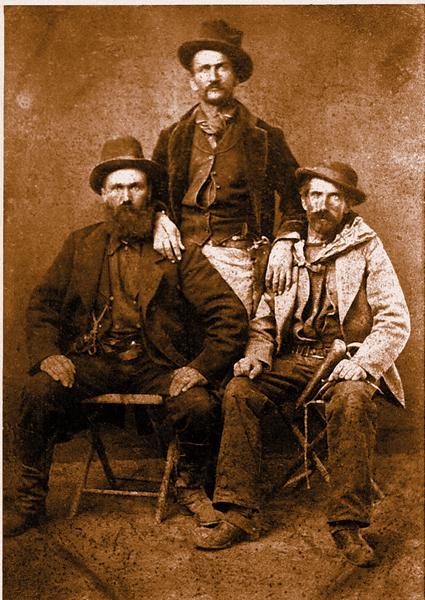

Motley Crew of Rangers

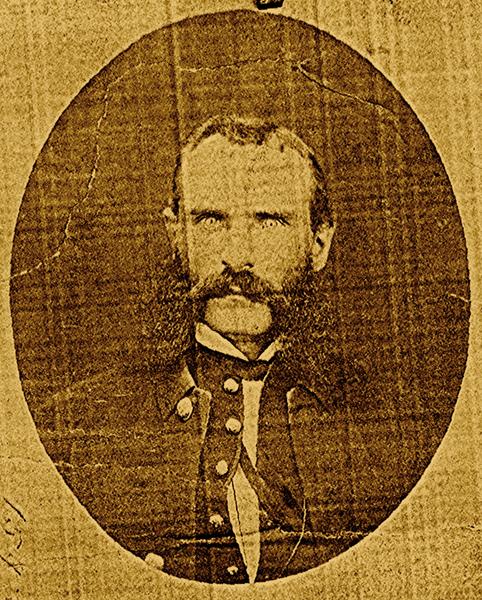

Texas Ranger Lt. John B. Tays (left) makes a serious tactical mistake when he leaves the Ranger compound with Howard to discuss terms of a settlement. He separates himself from his command and does not provide instructions for the Rangers left behind. Everything unravels when Barela shrewdly detains Lt. Tays in another room, then promises Atkinson freedom if he goes back to the compound and convinces the Rangers there that he has bought their freedom. Exhausted and unsure of what to do with Tays gone, they comply. Once outside, they are surrounded and disarmed. Thus, Company C becomes the only Texas Ranger outfit ever to surrender.

The unit was formed only months before, when authorities in Austin ordered Maj. John B. Jones of the Frontier Battalion of Texas Rangers to go to El Paso and form a unit of 20 men to deal with the growing crisis there. Although an excellent judge of men, Jones took whoever he could get. They were undoubtedly decent fighters, but their training was nil. Jones found these men through an ad he ran in the Mesilla Valley Independent, stating his intention of “recruiting a company to put down the El Paso County mob. Reliable men with horse and Winchester rifle will be paid $40 per month and board. Here is a chance to serve your county!”

Where Was the Cavalry?

Thanks to the modern marvel of electromagnetic communication (the telegraph), officials in Washington and elsewhere (see map, above) were in immediate communication about the situation at San Elizario. Even though the U.S. Army committed troops from every available post within a 200-mile radius, no one arrived in time to save the lives of Howard and the others.

The most damning aspect of the siege is that Capt. Blair was in the county with about 20 troops when the fighting started. He marched with his men to San Elizario on December 12, but he was intercepted by Chico Barela and a large group of insurgents just outside town (some reports say within 300 yards of the plaza). Barela intimidated him into retreating back to Franklin. Blair then wired his superiors a series of reports covering his tail (and lack of direct action), and remained there until after the executions.

Colonel Edward Hatch arrived in Franklin with another company or two (very small outfits). He had intended to wait until the other six or seven companies arrived, but he decided to move quickly down the valley. He made it all the way to San Elizario with 54 men, but most of the insurgents had already fled. Meanwhile, the Texas Rangers and Silver City rogue civilian outfit moved down the valley behind him and avenged the executions by killing civilians and several insurgents who had remained behind.

In Washington, Chicago and Fort Leavenworth, the frustrated generals couldn’t figure out what the delay was in getting the army into action.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

On December 18, the Texas Rangers were released, without their firearms. They vowed vengeance. Most of the insurgents flee to Mexico.

Colonel Edward Hatch arrived on December 21 with lead elements of the Ninth Cavalry, as did 30 Silver City Volunteers led by John Kinney and Grant County Deputy Sheriff “Dangerous Dan” Tucker.

El Paso Sheriff Charles Kerber led the Rangers and Silver City men on a killing spree in Ysleta and Socorro before Col. Hatch put a stop to the mayhem.

Major hostilities ended by 1878, yet guerrilla activity and crime continued to plague El Paso County.

In 1879, Benito Gonzales, the new sheriff, and George W. Baylor, El Paso’s new Texas Ranger commander, tacitly decided not to pursue anyone further for Salt War crimes. Slowly, the Salt War faded into the past. The shame of the Texas Rangers’ surrender is still felt to this day.

Recommended: Salt Warriors: Insurgency on the Rio Grande by Paul Cool, forthcoming from Texas A&M University Press.

Photo Gallery

Chico Barela meets the Blair detachment and intimidates them into turning around and going back to Franklin. This is the deciding factor in the fates of the Rangers and Howard.

– Courtesy University of Texas / El Paso –

– Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

– Courtesy Larry Wayne Zickefoose –