I sat in the front row of a school auditorium watching girls compete in a princess contest. This was not a competition of fancy hair and youngsters wearing makeup, but rather a tradition dating back decades.

I sat in the front row of a school auditorium watching girls compete in a princess contest. This was not a competition of fancy hair and youngsters wearing makeup, but rather a tradition dating back decades.

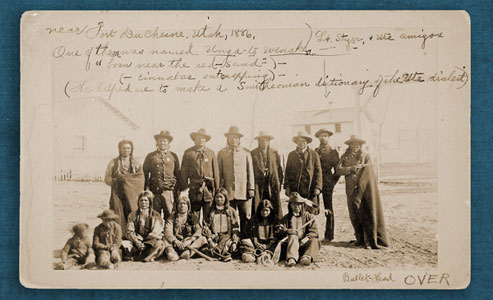

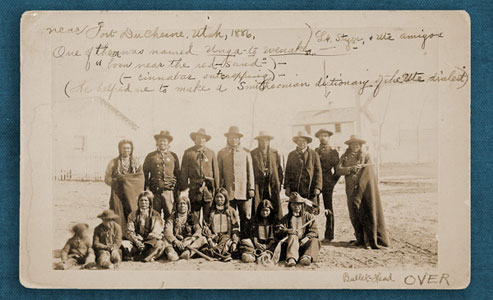

These girls were seeking to become the young princesses of the Northern Ute Tribe in Fort Duchesne, Utah.

The tiniest of the girls shared a story she had learned from her grandmother. One older contestant spoke about her desire to travel, to take part in the powwows and tribal celebrations held around the region, as well as the tradition of her clothing. All wore beautifully made garments. They had on dresses of supple tanned buckskin and brightly colored cloth. Their beaded moccasins were custom fitted to their feet and topped with leggings also displaying intricate beadwork. Their accessories included feather fans and shawls; some wore feathers or beaded bands, similar to a crown, over their shiny raven-colored hair.

As the girls spoke or answered questions, they clearly expressed a desire to uphold tradition, to share the stories that have been passed down to them and to make their parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles proud. They talked of their garments, explaining how they were made—and by whom. In most cases a devoted mother was involved, but these outfits had multi-generational influence as grandmothers, aunts and the girls themselves helped craft the clothing.

In early spring, these princess contests take place across the region, and they offer visitors a great opportunity to learn about Ute culture.

My attendance at the Northern Ute princess contest came just a few weeks before the Bear Dance held at Fort Duchesne. This annual tribal gathering also takes place in the spring, usually May or early June. The dance lasts four days, often going late into the evening. Men and boys gather on one side of the bear dance corral; several of them sing and make unique music using notched sticks (or rasps or tin boxes) and deer bones or small sticks that, when run over the rasps, make a rattling sound like the rumble of a bear waking up in the spring or of an early spring thunderstorm passing over the land. Women and girls, wearing dresses and shawls, sit or stand on the opposite side of the circle, often crossing the open dance area to choose a partner by flipping the edge of their shawl toward a male dancer.

Not everyone dances. Some people simply watch, socialize and enjoy the atmosphere, eating fry bread and bowls of beans. But if you do dance (the steps are fairly easy to pick up, even for a novice like me), the event is a social celebration where you can make new friends or renew acquaintance with older ones.

These Northern Utes on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation are primarily from the tribal bands that ranged across west-central and northern Colorado and central and northern Utah. Before being forced onto reservations, the Tabeguache (also called Uncompahgre), Grand River and Yamparika (or White River) tribal bands lived in Colorado in the valleys of the Gunnison, Uncompahgre, White and Grand (or Colorado) Rivers. The Uintah Utes inhabited the Uintah Basin, including the Great Salt Lake Basin.

Stories of Utah’s Five Tribes

Leaving the Uintah-Ouray Reservation and the Fort Duchesne Bear Dance, I head to Salt Lake City to visit the Natural History Museum of Utah at the Rio Tinto Center. This marvelous facility takes you from the era of the dinosaurs through the development of life and ultimately to the stories of the people of Utah.

In the American Indian gallery, listen to the tales told by tribal representatives from all of Utah’s five tribes: Ute, Paiute, Goshute, Northern Shoshone and Navajo. In one film presentation, the Ute Bear Dance traditions are shared from the perspective of my good friend Northern Ute Elder Clifford Duncan and his grandson Joey Kanip. The storyteller’s circle features a variety of tales shared by tribal members, including some told by Duncan.

My next destination is Price, Utah, where I stop at the Prehistoric Museum to view Ute displays of baskets, pottery and art.

I also head outdoors, where I can see evidence of the region’s native people that has been left behind in the form of pictographs and petroglyphs. Nine Mile Canyon offers one of the greatest concentrations of Indian rock art in the world. To reach the canyon, I head east out of Price to Wellington, turning north to begin the journey into the canyon.

This is remote country, and your cell phone likely won’t work. You will find few service stations in the area, so stock up with water and whatever food you need for the day, then begin exploring. The once rugged, rocky road is now paved, giving you access to some of the key sites using any type of vehicle. You can explore backcountry roads, but for them, you will require a good map, a four-wheel drive vehicle (high clearance recommended) and the service of a guide, if you are not familiar with the region.

I spent the night at the Nine Mile Ranch Bunk ’n’ Breakfast, about 25 miles north of Wellington. Lodging in the main house was comfortable. Ranch owner Ben cooked a good ranch breakfast, then he and his wife, Myrna, took the time to visit with me about the canyon, giving advice on where to visit. At times Ben leads tours into the canyon and its backcountry, but I was adventuring on my own.

Leaving their ranch (which has two rooms in the main house, small cabins and a campground), I drove deeper into Nine Mile Canyon, guided by the map brochure I picked up in Price, but I almost did not need it. Driving just a couple miles from the ranch, I saw petroglyphs on the canyon walls. They are visible from the road, but I walked over to view them from a close distance.

For most of the day I drove from point to point, getting out and hiking closer to explore the native art that comes from both Ute historic culture and the much older Fremont culture. The diversity of the rock art and the large number of features you can see is amazing. That this canyon had herds of bighorn sheep is evident; many of the drawings dating back for centuries depict such horned animals.

The canyon walls feature geometrically shaped men from the Fremont culture and more recent drawings showing men with bows and arrows who are riding or leading horses. Duncan has told me these rock images may represent story, myth or spirit. I make no effort to interpret them, but I do soak in the sounds of the place: a hawk keening, an occasional car, wind rustling the juniper trees. In the midst of all this beauty, I imagine the early visitors to this canyon who took the time to create these art forms.

The Great Hunt is one of the better-known and more impressive pieces of rock art in Nine Mile Canyon. It is large—approximately three feet across—and depicts dozens of hunters. Using the tour guide brochure that identifies its location by mile marker, you can actually see The Great Hunt as you drive on the road, but a new interpretive area allows you to explore it more closely, by parking and walking down a trail for a few hundred yards.

I could have spent much more time exploring Nine Mile Canyon (which also has a healthy dose of history related to homesteaders, stage emigrants and outlaws), but it is time to hit the trail again, and I’m soon driving south across Utah and into Colorado. This was, and still is, all Ute country.

Tales of Ute Country

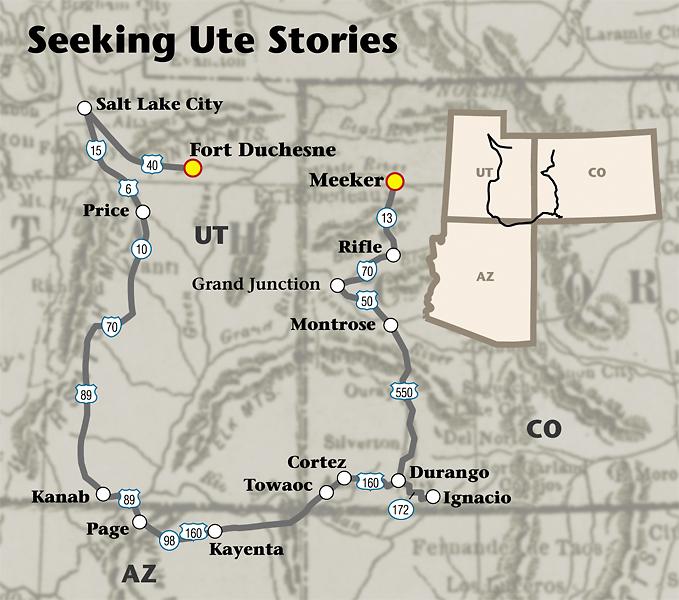

From Price, I head through Kanab and on to Page, Arizona. From there, I reach Kayenta, before driving toward Four Corners. Much of this land is now part of the Navajo Reservation, but the Utes traditionally lived in southern Utah, Colorado and New Mexico.

The Weeminuche band of Utes occupied the valley of the San Juan River and its northern tributaries in Colorado and northwestern New Mexico. This tribal unit is known today as the Ute Mountain Utes, with its tribal headquarters in Towaoc, Colorado. Guided tours of Ute Mountain Tribal Park are available in Towaoc, or you can get a dose of modern Ute culture at the Ute Mountain Casino and Resort south of Cortez.

To learn more about the other tribal bands, the Mouaches, who lived on the eastern slopes of the Rockies, from Denver, near Las Vegas, New Mexico, and the Capote band, which inhabited the San Luis Valley in Colorado near the headwaters of the Rio Grande and northern New Mexico, I travel to Ignacio, Colorado. These Mouache and Capote bands are now collectively the Southern Utes, with their reservation headquartered in Ignacio.

The Southern Ute Cultural Center & Museum in Ignacio is another excellent place to learn more about the culture of these people. In the Ute lodge, you can sit and listen to the creation story of the tribe or to a more modern tale. You get the opportunity to observe outstanding examples of Ute clothing, tools, implements, weapons and artistry. The baskets or beadwork, pottery and music are all intelligently interpreted.

Don’t be surprised if you find yourself greeted by a young woman at the front desk, only to see her story play out on a big screen as she speaks of her role as a princess for her tribe. As you walk through the center, you will hear the sounds of the Bear Dance or powwow drumming.

Just a short drive or walk from the museum is the Sky Ute Casino and Resort, which houses some of the most uniquely appointed rooms in the region, giving you a place to relax and reflect on the lives and culture of these native people.

As at the Uintah-Ouray Reservation at Fort Duchesne, a spring Bear Dance is held each year at Ignacio. The tribe here also hosts cultural events that range from a tribal fair and powwow held annually the second weekend in September to a veterans powwow held each year in early November.

White River Ute Tragedy

From Ignacio, I backtrack to Durango and turn north to Montrose, where the stories of Ute Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta, are a focus of the Ute Indian Museum. But my travels will soon be taking me into a darker heart of Ute tribal narrative.

The White River Utes were congregated in Meeker in the 1870s when the tribe was first moved onto a reservation. The town gets its name from Ezra Meeker, who served as the Indian Agent at the White River agency. The White River Museum, a repository of pioneer collections, shares the tragedy of the Meeker uprising.

In 1879, Meeker attempted to force the tribe to give up horse herds and to begin farming and agricultural activities. He had their horse race track plowed under and generally created tension with the tribe. Then Meeker went a step further and called for assistance from federal troops, who marched south from Fort Fred Steele in southern Wyoming.

The troops and the Utes met north of Meeker in September 1879 in an engagement that left Maj. Thomas Tipton Thornburgh and other soldiers dead and under siege for days before relief troops arrived. The Utes attacked Agent Meeker and others at the agency, killing several of them and taking Meeker’s wife, daughter and other women and children hostage before ultimately surrendering and releasing the captives.

These events resulted in the removal of Northern Utes from Colorado to their current reservation lands in northeastern Utah. The next few years would witness other altercations between the tribes and the settlers in Colorado, including an incident in late summer of 1887 when the Northern Ute Chief Colorow and other tribal members went on a hunting and berry gathering trip into Colorado. Tension was high among settlers and the Utes, leading to several conflicts that brought about deaths on both sides: eight Utes and two soldiers, plus injuries to several others.

Colorado Gov. Alva Adams ultimately ordered the state militia to the region, leading to additional conflict and the wounding of Colorow. The Utes fled toward Utah, where they were met by Buffalo Soldiers from the 9th Cavalry who helped defuse the situation. The Utes lost the horses, sheep and goats they had taken into Colorado, along with the meat, hides, berries and other supplies they had accumulated during their hunting expedition. Their chief, Colorow, died of his injuries in 1888.

Nearly 130 years after Meeker’s death, in 2006, the town of Meeker attempted to re-establish ties with the White River Utes by welcoming the Utes to perform their Bear Dance. The town continues to work with Ute historians to reinterpret the historical sites around Meeker so as to share the perspectives of all those involved in the Meeker tragedy. It’s about time.

Photo Gallery

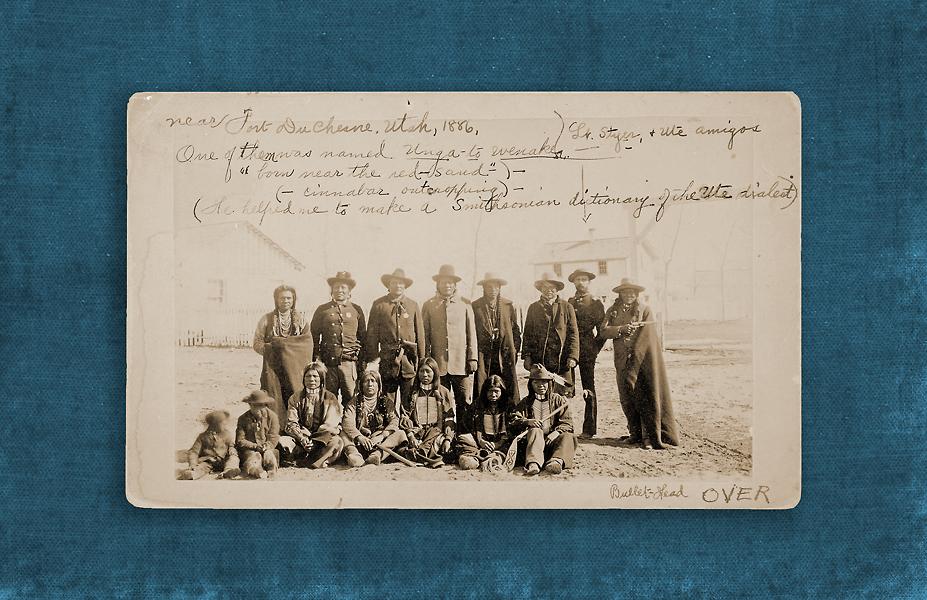

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Southern Ute Cultural Center & Museum –

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted –