If you mention the word “sports” in the same breath with the “Old West,” most people will give you a blank stare.

If you mention the word “sports” in the same breath with the “Old West,” most people will give you a blank stare.

Yet sports were as much a part of frontier life as the cowboy riding a fence line—even more so, since sports were there long before there was a fence line for the cowboy to ride.

The earliest games in the Westward Expansion were those played by the American Indian. Most of these are lost to history now, but one still thrives today—Lacrosse. More than 500 years old, Lacrosse probably began as a sacred contest. Later, it became a way to condition warriors for battle and was also used to settle inter-tribal conflicts. Hundreds of braves played on each side, wielding three-foot-long sticks with a netted loop at the end. The ball was deerhide stuffed with deer hair or sometimes wood. The goals ranged from several hundred yards to more than a mile apart. It was no-holds-barred, played from sunrise to sunset—sometimes more like a human demolition derby than a game—and injuries were commonplace. To early French-Canadians, the Indians’ sticks looked like a bishop’s crozier—la crosse—and that’s what they named the game.

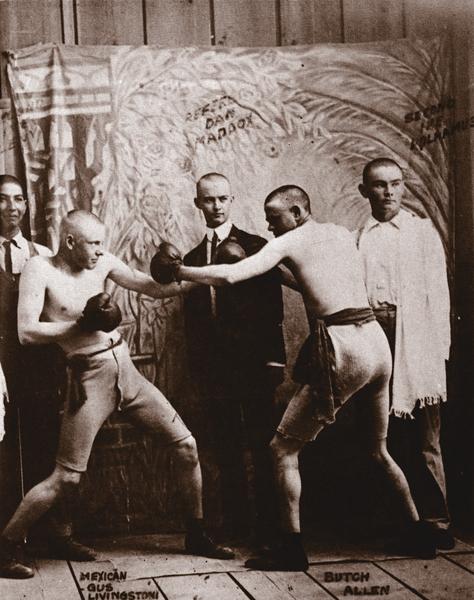

Most of the earlier sports in the Old West were rugged, often brutal and sometimes bloody. Bull and bear fights were frequent events in the early to mid-1800s. Parties of men took to the wilderness to capture a Grizzly, truss it and cart it into town, which was no mean feat in itself. Then they would capture a wild range bull, which had long, spiked horns. These two creatures were pitted in a fight to the death in an adobe corral, or sometimes they fought on the main street of town, with both ends barricaded. (Some reports claim that New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley, while witnessing one of these matches, was inspired to create the Bull and Bear symbols that still represent the arena of Wall Street today.) Dogfights and cockfights were also popular, as was a rough-and-tumble combination of boxing and wrestling.

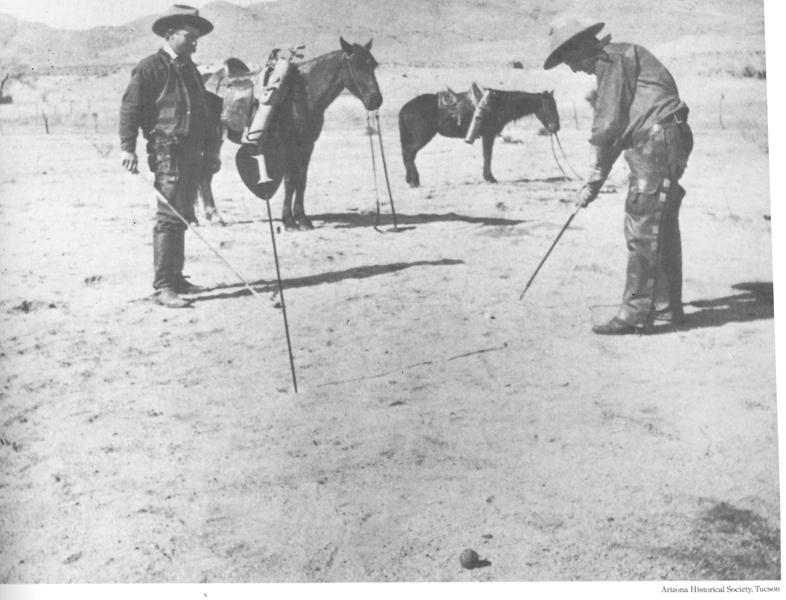

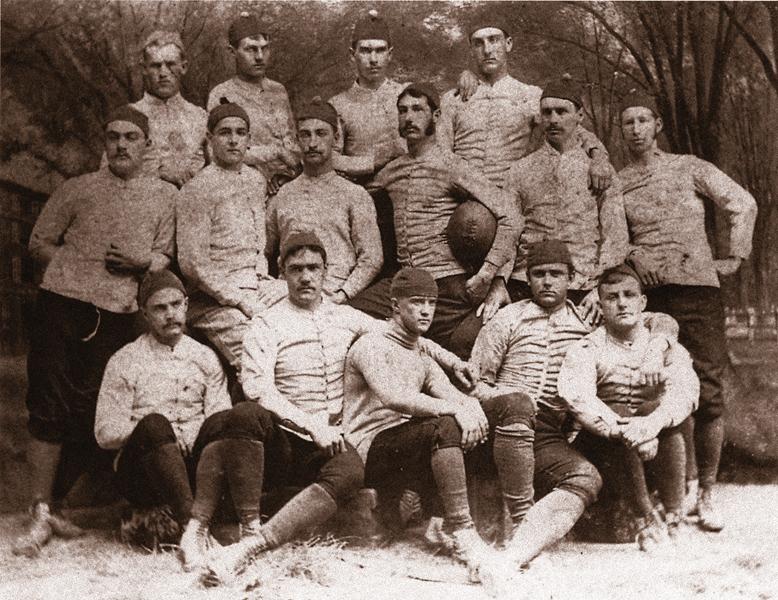

The sports and contests that developed later were, happily, less damaging to the participants. In what might be thought of as the middle period—the transition between the roughhouse origins and sports as we know them today—many of the competitions were derived from skills that were necessary to life during that time.

Foot racing and horse racing encouraged communities, often widespread regions, to support its champions. Marksmanship contests were held regularly, with rifle matches at ranges of 200-500 yards. “Big Windy” competitions held sway for decades. In these, tellers of tall tales would try to outdo each other. Prizes were awarded, and towns heaped accolades upon their star fibbers.

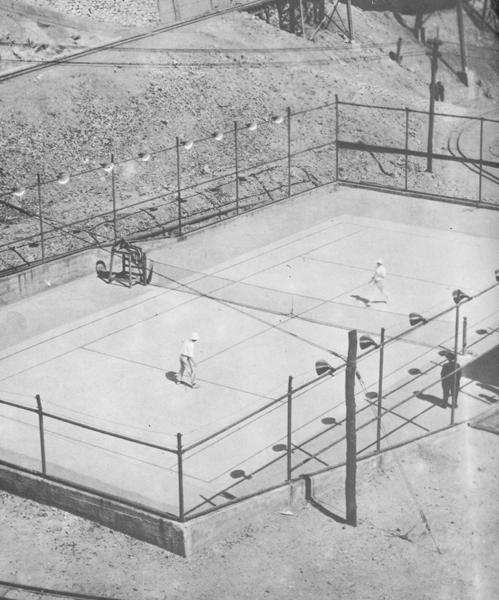

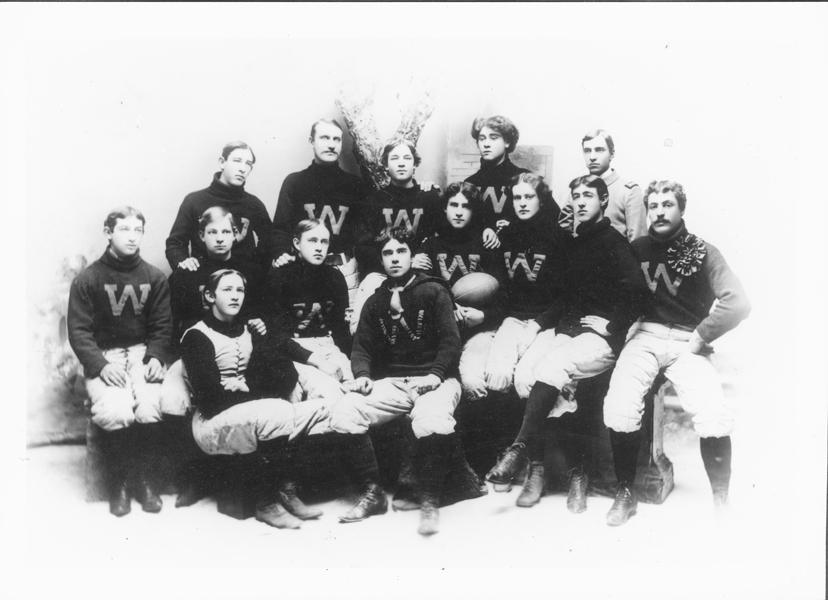

Where there was mining, logging and river commerce, competitions involving specialized talents evolved. Rock drilling, steamboat racing, log rolling and ax throwing always drew crowds. There were ice skate, roller skate, bicycle and sleigh races, as well as gymnastics and prize fighting.

Sports in the Golden State

Bowling came to the Old West in the mid-1800s. The game was particularly popular among German immigrants, and it traveled westward with the settlers. One of the strangest alleys in the history of the sport was built in California in 1866. A giant

Redwood was felled and planed flat on one side; then a clubhouse and long shed were erected atop it. The bowlers rolled their balls down the flat, heavily-waxed surface of a majestic Redwood-turned-bowling alley. By the turn-of-the-20th-century, bowling halls and leagues were firmly entrenched from the Mississippi to the Pacific.

California also boasted the earliest skiing competition in the Old West. Norwegian settlers in the Sierra Nevada region introduced the sport in the 1850s. With an average seasonal snowfall of 408 inches, communities were isolated from each other and cut off from the rest of the world for months at a time. An immigrant named Jim Thompson, the most famous of the early skiers in the region, may have been the first man to popularize skiing. He built his own skis, and in the late 1850s, he contracted to carry mail from Calaveras Grove in California over the Sierra to Carson Valley, Nevada—a run of 90 miles, with 60-100 lbs. of mail on his back. Called “snowshoeing” for the first few years, skiing caught on instantly and was quickly organized into a competitive sport.

The Sacramento Union of March 28, 1868, reported: “Our great snowshoe racing tournament, under the direction of the Table Rock Snowshoe Club, just completed, has been the all-absorbing event of the past two weeks.” Huge sums of money were bet. Thompson himself set an early record, skiing 1,600 feet in 21 seconds. He regularly made jumps of 50 feet or more from smaller precipices, and once jumped an astounding 180 feet.

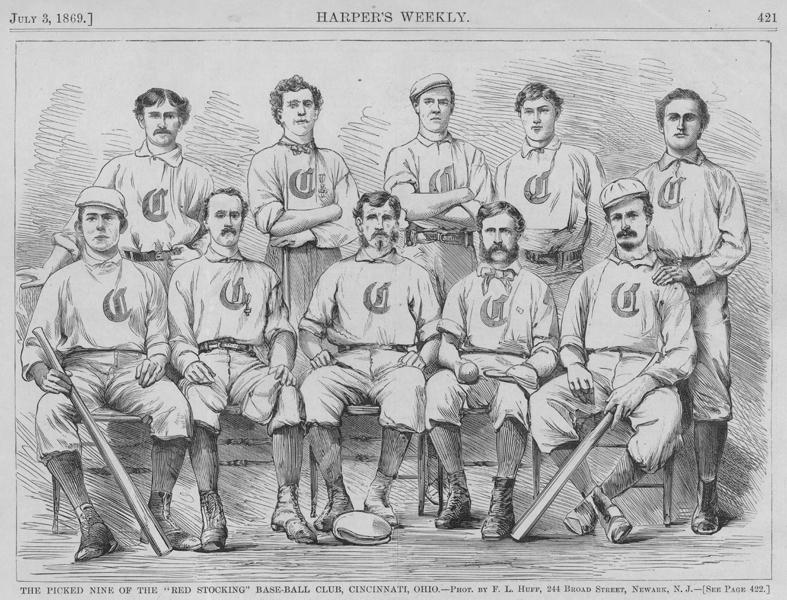

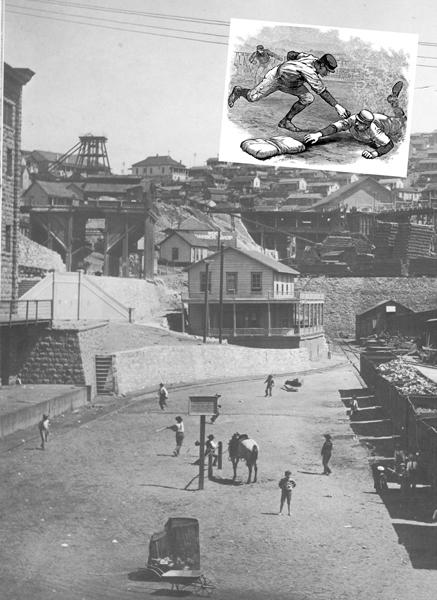

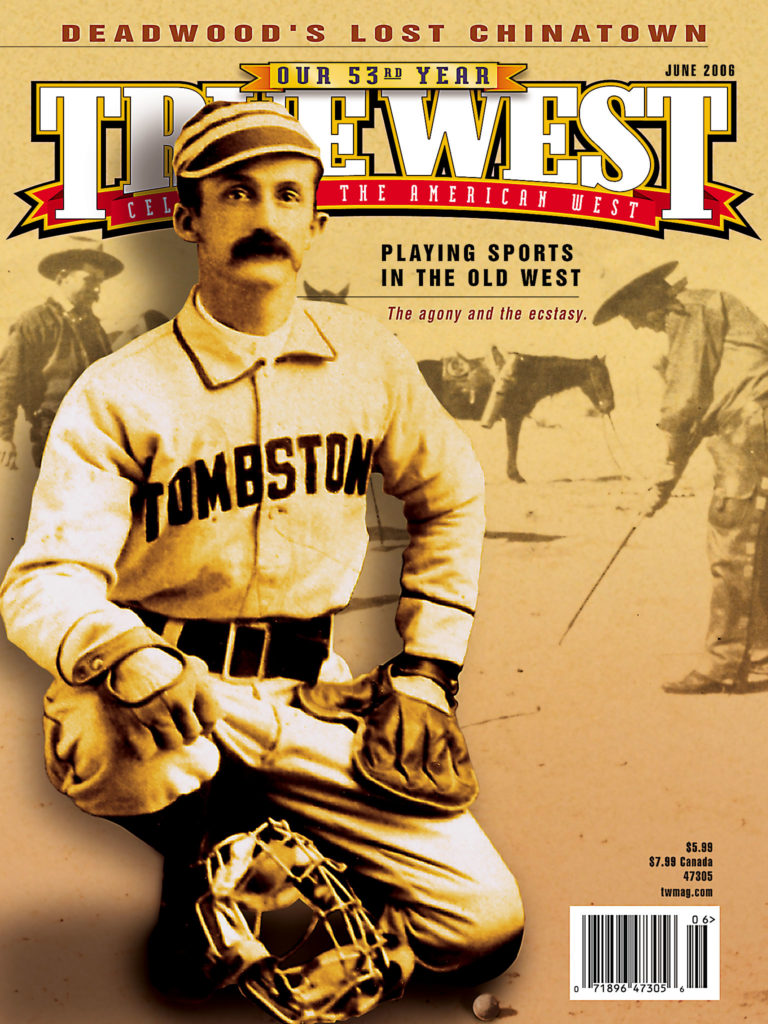

Take Me Out to the Ball Game

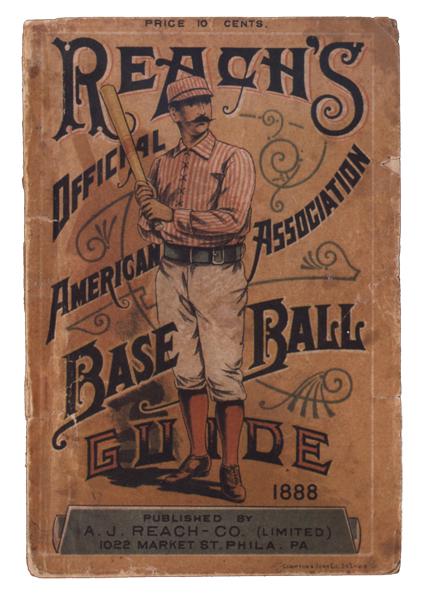

Baseball spread throughout the Old West around the late 1840s, and it was played regularly in many areas on a sandlot basis for the next 20 years. Then, in 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings—America’s first professional team—departed westward from St. Louis on a rail tour. In San Francisco, the Red Stockings played the local amateur team, the Eagles. The crowd, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, was gracious in defeat: “It is easy to see why they adopted the Red Stocking style of dress, which shows their calves in all their magnitude and rotundity. Everyone of them has a large and well turned leg and everyone of them knows how to use it.”

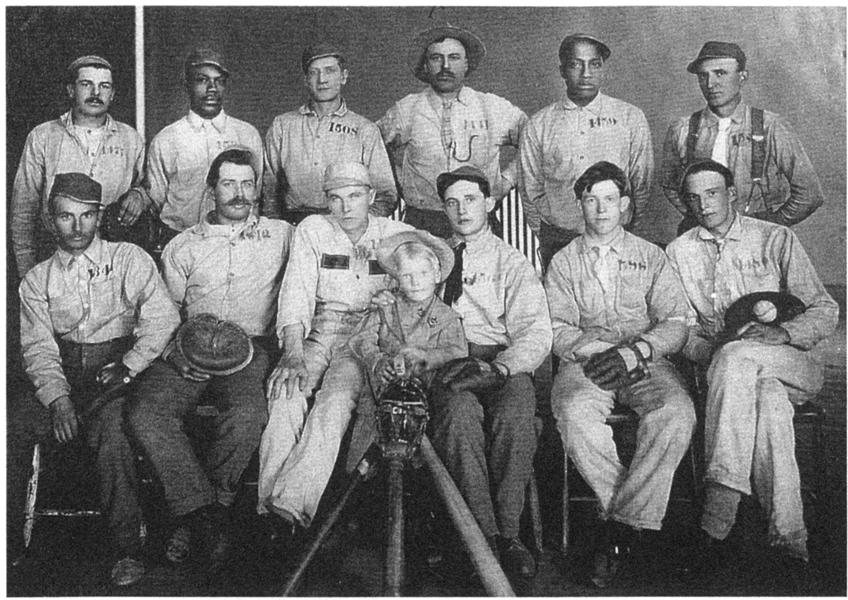

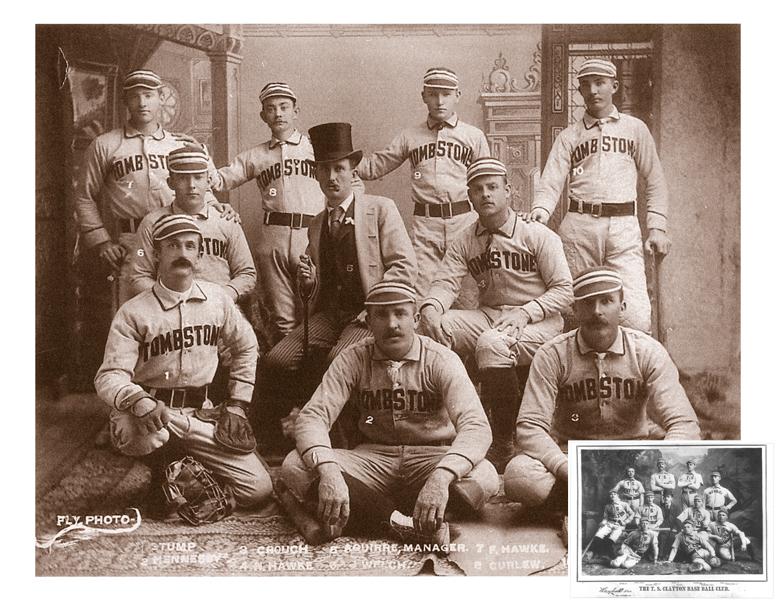

The Red Stockings played to sell-out crowds throughout the tour. Enthused by their skill and the thrill of the game, the West went baseball mad. Over the next decade, cities and towns from the Missouri to the Pacific formed professional and semi-professional teams of their own.

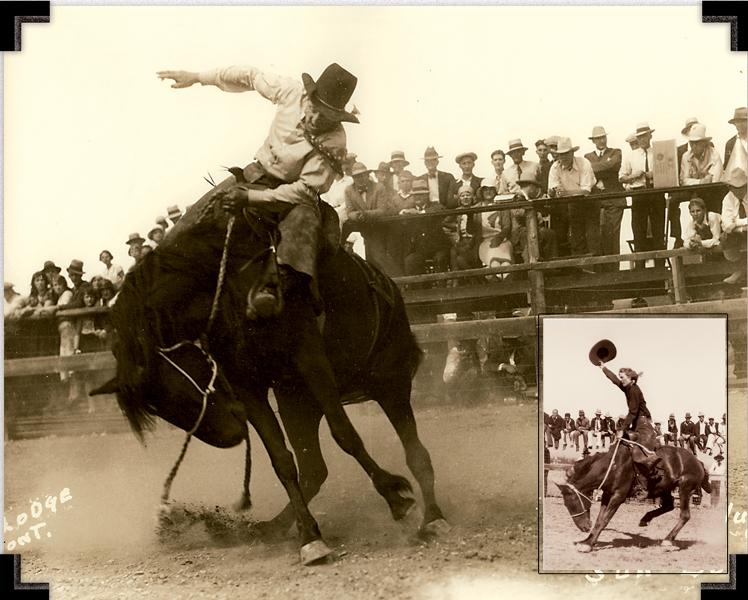

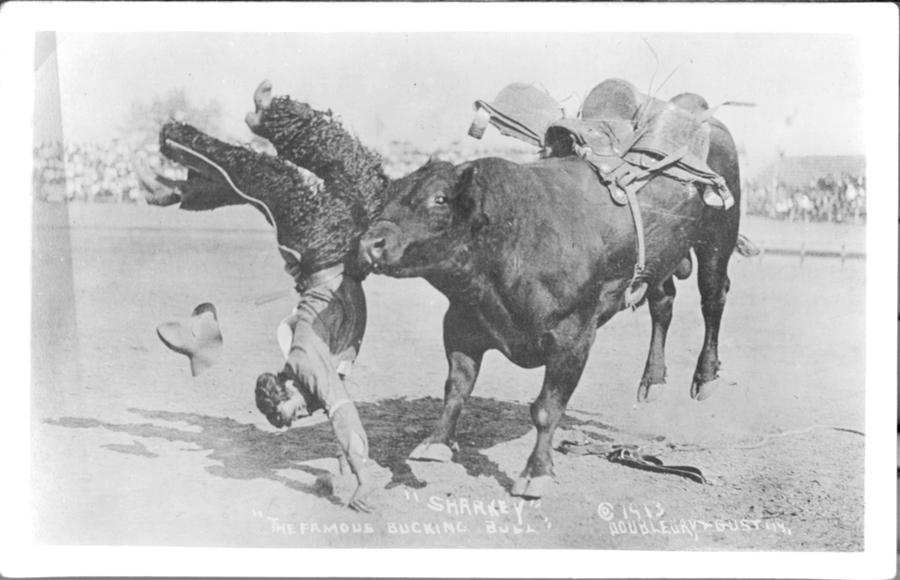

Eight Seconds to Glory

Rodeo is the only American sport ever to emerge from an industry—the cattle trade. Nearly all of its events—broncbusting, bulldogging, steer roping, fancy riding, trick roping—stem directly from the skills cowboys needed to work cattle. Cowboys took the Spanish rodear, loosely translated as “to surround or encircle,” and changed it to rodeo, to mean a roundup. On days when there was time to spare, the cowpunchers from two or three outfits would get together to compete for small purses or personal bets.

Out of these informal contests grew organized competition, as well as many traveling Wild West shows. One of the most famous of these was the Miller Brothers’ 101 Wild West Show, which originated on the family ranch near Ponca City, Oklahoma. The show featured several men who would win national fame, and two who would be remembered for generations: Will Rogers and Tom Mix.

As the era of the Wild West shows passed in the 1920s, one of its legacies, the rodeo, went on to become a major sport. Today, the Professional Rodeo Association draws millions of spectators to events each year and awards the cowboy competitors millions of dollars in prize money.

We’ve come a long way from the Old West, where a town’s baseball diamond was often more famed than the O.K. Corral.

Matt Braun has been honored with the Owen Wister Award for Lifetime Achievement by Western Writers of America.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Hubbard Museum of the American West –

– Courtesy National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum –

– Courtesy National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum –

– Tombstone Tigers photo courtesy Arizona Historical Society / Tucson AHS #17867 –