Myra Maybelle Shirley, better known to the world as Belle Starr, made a name for herself in a world of shoot- ’em-up men.

Myra Maybelle Shirley, better known to the world as Belle Starr, made a name for herself in a world of shoot- ’em-up men.

She had three outlaw husbands, and depending upon who you listen to, she reportedly had romantic relations with any number of other famous desperados, even bearing a love child with Cole Younger. Victorian-era news reporters couldn’t resist her scandalous allure. The legend that became her is all of that and more—a hint of culture on the outside, a heart of gold and hellfire in between.

Whether you believe Belle Starr was a femme fatale who rode sidesaddle in red velvet with a pearl handled gat holstered at her waist or simply white trash whose only claim to fame was a knack for self promotion, one thing about her legend still rings true. Something about the Bandit Queen draws men to her like flies to sugar, even today. Nearly a century and a quarter after her mysterious death by an unknown assassin, her siren’s call once again found the ear of a man who would love her.

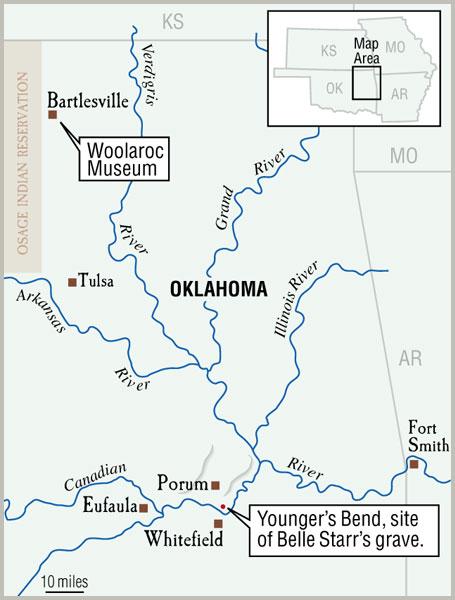

Dr. Ron Hood, an orthopedic surgeon in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and his wife, Donna, recently purchased Belle’s gravesite near the Eufaula Lake Dam outside Porum, Oklahoma, from the daughter of Claude Hamilton, a local barber who was all but a legend himself in Belle Starr Country. Hamilton came to Oklahoma from Colorado in the late 1930s. Like many an amateur historian, he was convinced that outlaws buried their loot instead of spent it buying protection and paying lawyers, or flinging it away on whiskey, women and song. For 50 years this barber with gold–crazed eyes roamed the sandy, timbered slopes of Hi-Early Mountain in search of the rich hoard he just knew had to be buried there, yet had never been found.

But perhaps Hamilton came to learn, like Hood has, that the treasures of Younger’s Bend aren’t counted in coin, and they can’t be dug up with pick and shovel, a bulldozer, scuba gear or even a few sticks of dynamite (yes, Hamilton tried them all). The riches of Younger’s Bend are being able to put your feet on the very ground where history rode. It’s physically breathing in the land, feeling a century wind away and seeing the country turn wild again and hard to curry below the knees.

When I asked Hood what one thing most intrigued him about the site, he replied, “It’s simply the convergence of history. So many historical figures passed through here, from Civil War soldiers, outlaws and lawmen, to explorers mapping the Western frontier.”

His assertion is as accurate as the bullet out of a straight-shooting Winchester. Belle’s home at the southwestern edge of Cherokee Nation lay just to the north of the California Trail from Fort Smith, Arkansas, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, and not far east of the famous Texas Road out of Missouri. Her connections to former Confederate bushwhackers and the intersection of two major thoroughfares nearby made her home by Hi-Early a natural way station for outlaws the likes of the James-Younger Gang, Jack Spaniard and others. More than one posse of deputy U.S. marshals came to Younger’s Bend to serve warrants or to search for stolen horses.

This plethora of famous traffic, in addition to Belle herself, is what led Hood to purchase the 55-acre tract of land. Belle’s cabin and barn were torn down in the 1930s, and the clearing that had once surrounded it is now a timbered thicket. All that remained to mark the exact location was a faint, overgrown trail leading to Belle’s grave, itself in a state of ruin.

Belle’s grave has always had more than its share of visitors, despite its seclusion and lack of advertisement. Within a month of her burial in 1889, the grave was robbed, reportedly for stolen loot believed to have been placed within her coffin. The only known treasure taken was her jewelry and her pistol. Her grave had been a simple affair, but after the looting, her daughter, Pearl, a high-toned prostitute in Fort Smith, ordered a stonemason to construct a rock monument over her mother. He stacked local sandstone into a box, with two large slabs forming a double pitch roof over the structure. A marble tombstone bearing a Masonic Star, a bell and an image of Belle’s favorite horse, Venus, stood at one end of the roof.

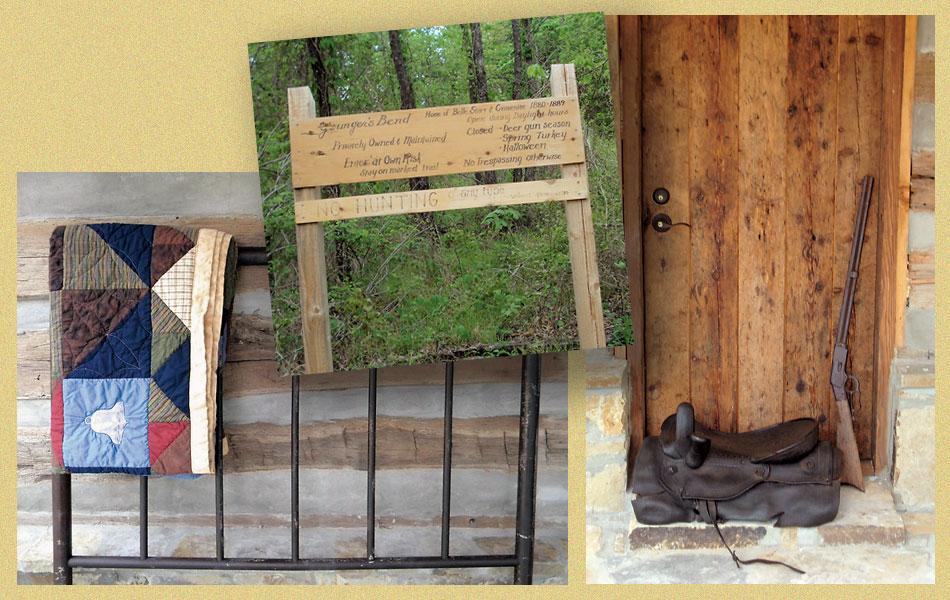

During Hamilton’s tenure, vandals destroyed the tombstone, carting away parts of it. He erected a chain link fence around the grave and replaced the tombstone with a replica, storing two large pieces of the original under his bed for inspiration in his treasure search.

What Hood inherited was by no means the gravesite recorded in photos in several Western history books. The large slabs of the roof had fallen in, as had much of the mortar joining the flat stones of the walls. The tombstone no longer sat on the end of the monument, but some caring soul had found it lying facedown in the dirt and propped it up against the wall. With the utmost care aimed at keeping the grave in its original state, Hood and a professional stonemason set to work to restore it. The chain link fence was done away with, but the low concrete footing that Hamilton had erected for a viewing border was left in place. The grave now looks almost as it did the first time I saw it in the early 1980s.

What looks entirely different is the trail leading to the grave. Ice storms and shady growth had all but hidden the path from those without a dose of woodcraft. The Hoods decided to blaze a new trail to the grave. Now the interpretive path follows an easy climb up the mountain, with cedar signs denoting different plant species.

Hood’s original intentions for the property had been for a weekend getaway, but to his mind, an ordinary home would not do for the site. Through some careful searching and a little luck, he located a standing 1850s cabin in California, Missouri, near Belle’s hometown of Carthage. He purchased the cabin and relocated it to Younger’s Bend. The hardwood logs bearing broadaxe and adze marks were put back together according to the original plans, some hundred yards below the gravesite and ruins of Belle’s home. The building was originally a two-room, saddlebag-style cabin, with a double-sided fireplace in the center wall. He sought to find a blend of aesthetics and comfort, without totally ruining the original appearance, with stone chimneys that rise from either end of the cabin. The second floor loft also has a fireplace in each end, with the original peeled-pole rafters exposed overhead. In order to add space for modern conveniences, such as indoor plumbing, a small, framed addition was placed at the rear. A native stone porch runs the width of the building, and one can see a stunning view of the Canadian River bottom and the mountains from its shade.

Inside the cabin, wildlife mounts, antique furniture and an oil painting of Belle will soon decorate the space. The iron bedstead that served as a gate on the path to Belle’s grave for so many years has been restored and will once more be a bed. In a display of his keen sense of history, Hood left the welded gate hinges on the headboard.

Hood will be the first to tell you that as much history surrounds the site after Belle’s death as before. Hearing his tales of Hamilton lowering a boy down Belle’s well on a rope brings to mind all the folktales of the area. Porum, Whitefield and Eufaula are known as Belle Starr Country for good reason. Old-timers tell of the time when you couldn’t walk down the river bottom in Younger’s Bend without falling into a hole dug by Depression-era treasure hunters.

Hood has been lucky; finding the property listed with a realtor must have been akin to Hamilton finding a treasure map left behind in his shop in Colorado those long years ago. In the purchase agreement, Hood received an 1873 Winchester in .38-40 caliber and a sidesaddle reportedly belonging to Belle, as well as the two chunks of the original tombstone. Hamilton collected the gun and saddle over the years, and he got many of the Starr descendants to sign off on their authenticity.

Hood’s latest passion and hobby has become retracing the topographical locations of the events of Belle’s last night. Exploring trips on the property haven’t yet revealed hidden gold, but down the river a piece, his searching has led him to the remains of the Hoyt Ferry owned by Babe Hoyt, a Choctaw. Its wooden structure had long since been buried and preserved in the river sand, until low water levels last summer revealed one corner of it. Hoyt himself was at the ferry the night of Belle’s death. He saw her horse run down the lane with a bloody saddle, swim the river and race upstream toward her cabin.

The Hoods are already astounded by the number of curious passersby who have stopped to visit while he and his crew are busy with construction. What started as a family project has quickly led to a whole new set of friends with a common love of history. The Hood family intends to make the cabin available for weddings, conferences and weekend rental.

On a sunny spring Wednesday, Hood and I stood amidst the hardwood forest and talked of all things old and long past, of good men and bad, of wagons creaking down rutted trails and of a woman who lived and died with a gun on her hip and a fast horse beneath her.

Our eyes wandered across the slow river to the mountains in the south, as our spit-and-whittle conversation followed the outlaw trail to Robbers Cave and other hideouts amidst what is still a rugged country.

Watching him longingly run his fingers over the three notches filed into the comb of the Winchester’s buttstock, I fought down the urge to ask him if he too has the tombstone pieces under his bed. As all treasure seekers know, dreams can lead you to discovery.

Photo Gallery

– By Harold Brewer –

– Belle Starr: True West Archives; 1941’s Belle Starr: 20th Century-Fox –

A side view of Belle Starr’s cedar log cabin, published in Glenn Shirley’s 1982 book, Belle Starr and Her Times: The Literature, the Facts and the Legends, a standard reference on the bandit queen. During the 1980s, Glenn also served as historical consultant for True West Magazine.

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Brett Cogburn unless otherwise noted –