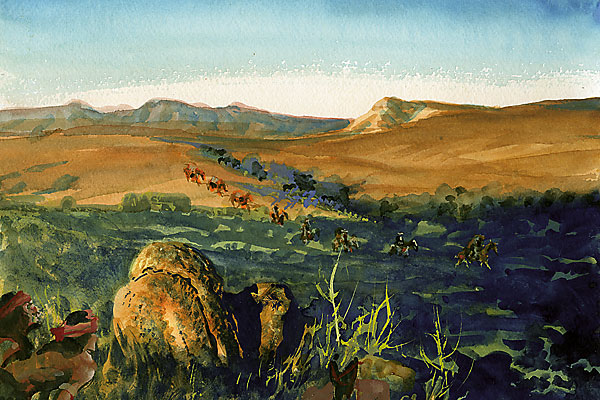

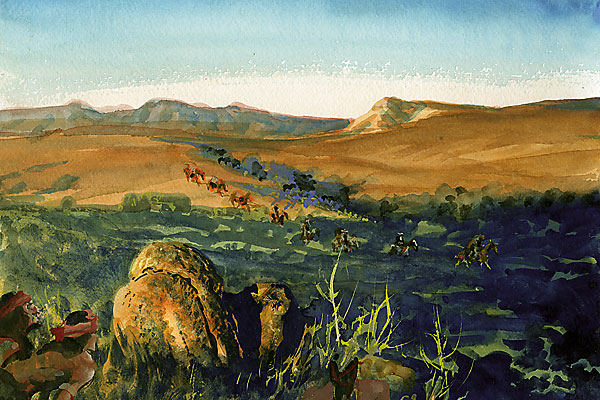

Five American prospectors set up camp near the junction of Turkey Creek and Tuscumbia Creek in the rough Bradshaw Mountains, about 30 miles southeast of Prescott, Arizona Territory. Although warned of hostile Indians in the region, the gold seekers—Frank Binkley, Samuel Herron, Stewart Wall, Fred Henry and D.M. Scott—are all veterans of Indian fighting and confident of their ability to ward off any attackers.

Five American prospectors set up camp near the junction of Turkey Creek and Tuscumbia Creek in the rough Bradshaw Mountains, about 30 miles southeast of Prescott, Arizona Territory. Although warned of hostile Indians in the region, the gold seekers—Frank Binkley, Samuel Herron, Stewart Wall, Fred Henry and D.M. Scott—are all veterans of Indian fighting and confident of their ability to ward off any attackers.

Eight horses (including three pack animals) are picketed away from the camp where there is good grass for feed. A deer killed during the day is skinned and cooked on the campfire.

Heading off on a twilight scout, Wall and Herron ride in a wide circle and turn up no sign of Indians.

After supper, the men turn in early to escape a swarm of mosquitos. The horses exhibit “some uneasiness about nine o’clock,” but the men ignore the disturbance.

An hour before dawn, a barrage of arrows rains on the camp, waking up the men who spring into action. One of the prospectors grabs a rifle, which, being wet, misfires; he takes out his revolver and begins to blaze away. The fight is on.

The Yavapais (estimated at 30-50 strong) open up a steady barrage of bullets, arrows and rocks as the prospectors fire back and dig in at the same time, with their sheath knives and a small shovel. They pile up saddles, packs and rocks to hide behind.

By the time daylight steaks the eastern hills, all the white men are wounded except Herron. A bullet has torn through Binkley’s nose and knocked out one of his eyes. Wall suffers a bullet wound through the body, and Henry is hit in the arm and the breast. Two horses are dead; another, full of arrows, staggers around the flat howling in pain. Binkley lays still in the brush and is presumed dead.

As the Yavapais press the attack, two of the prospectors, Scott and Herron, move higher up the ridge to avoid being flanked by the attackers. Wall and Henry attempt to hold the camp and the provisions, but Wall becomes too weak and can no longer hold up his gun. Henry stays, while Wall staggers up to the higher position. Wall then calls down for Henry to join them. As Henry stumbles up the ravine, the Indians, sensing he is too weak to fire, rush him, but he weilds two pistols and drives them back.

With the camp abandoned, the marauders descend upon the plunder, gathering up everything and hauling it up a hill about 400 yards away. They cut up the dead horses, build several big fires and start roasting horse meat.

Fearing that the Indians will attack them and try to wipe them out after feasting, the prospectors retreat higher up the draw, looking for a better defensive position. Neither Herron nor Wall can walk without help. Binkley is almost blind, and Scott only has one good hand.

Some 70 yards up the draw, Herron gives out and can’t continue. He implores his pards to leave him and save themselves, but they refuse, setting up a last stand under the shade of a large juniper tree.

As the men watch the Indians feasting on their horses, they decide Henry should make a run for it and take along Binkley. The two men crawl up the draw at about 11 a.m., but the Indians quickly spot them and head them off. Trying another direction, they are also denied that route and try a third.

As they make their way down a ravine, a Yavapai rises from behind them and says in Spanish and English “Where are you going, friends?” Henry points silently in one direction and walks the other way. The Indian let them go!

Walking all night, Henry and Binkley reach Walnut Grove at about 8 a.m. and sound the alarm. Ten men, led by the intrepid Jack Swilling, leave immediately. Arriving back at the scene by 2 p.m., they find the Indians long gone, but, incredibly, their three pards are still alive.

Armed to the Teeth

“According to the custom of the time in that country, every man was armed with a good rifle, and a pair of Colt’s revolvers. Although cap-and-ball weapons, these were powerful arms using a round ball of .44 caliber, backed by a heavy charge of black powder. Forty-four grains of powder could be used, but 40 was the common load at that time. Fred Henry had a Hawken rifle of .53 caliber which used a round ball weighing 32 to the pound. Wall’s Harper’s Ferry rifle was a percussion-lock arm using the same caliber ball with a charge of 70 grains of black powder; this load delivered at least 1,700 foot-seconds velocity. In the group was at least one double-barreled shotgun. Everybody had plenty of ammunition, and felt able to stand off any attack.”

– From “Indian Fight at Battle Flat” by Jack McPhee in the May 1967 issue of Frontier Times.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

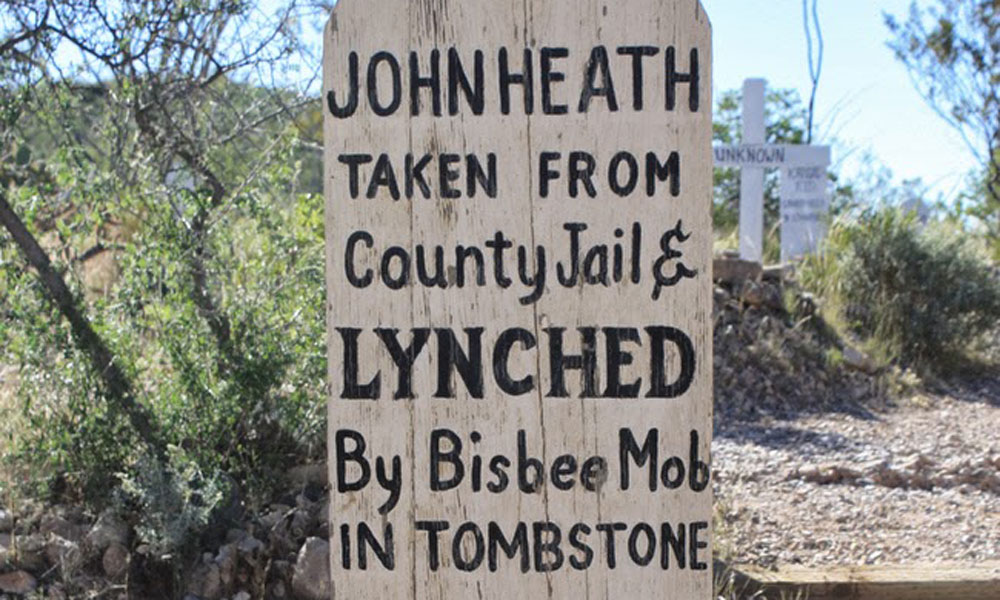

The wounded men were taken back to Walnut Creek, but Samuel Herron never regained consciousness and died on the ninth day after the fight. He was buried at Walnut Grove.

The rescuers claimed to have found 14 dead Yavapais at the scene of the fight; thereafter the location was known as Battle Flat.

Stewart M. Wall, who had some 14 wounds from the fight, traveled to his home in San Bernardino County, California, where he became the first city marshal and lived out his life.

D.M. Scott remained in Arizona and recovered full use of his crippled hand. He continued prospecting and hit it rich.

Frank Binkley also returned to San Bernardino. He and his wife became freighters, making several trips to Prescott, Arizona. Binkley fought the same band of Yavapais in the 1864 Skull Valley fight, in which 40 Yavapai were killed. Binkley told friends he felt he had avenged the loss of his eye.

Fred Henry stayed on in Arizona, with a brief respite in Colorado. He worked for the Copper Queen Mining Company and died in Bisbee in 1899.