Carl Fisher had a need for speed, and because he hatched the means for long-distance travel in the U.S., tourism to the American West took off 100 years ago.

Carl Fisher had a need for speed, and because he hatched the means for long-distance travel in the U.S., tourism to the American West took off 100 years ago.

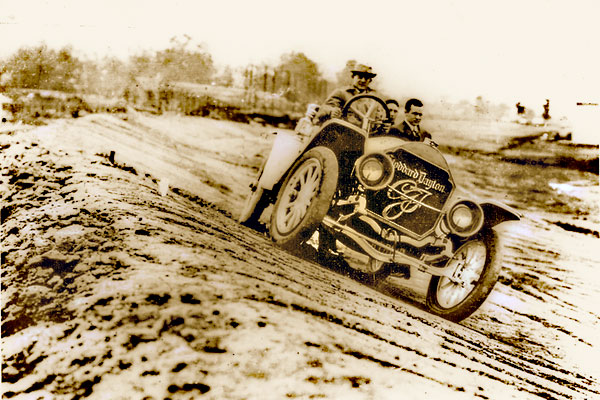

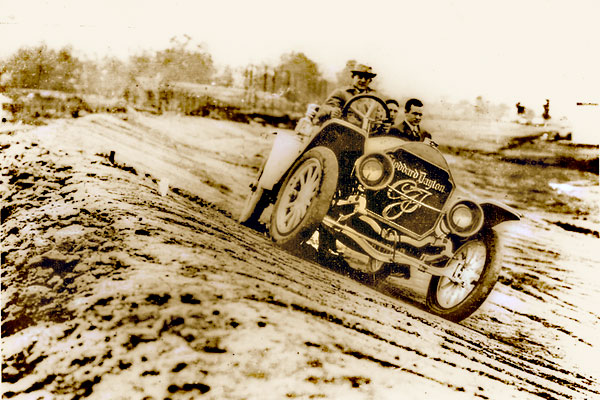

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1874, Fisher began what some believe to be the first car dealership, in his 20s. In 1904, his interest in a patent for acetylene headlamps gave his company a monopoly on car lights. Fisher made a fortune—and pumped it into his passion, auto racing. Truth be told: He was not even a great driver; he had bad eyesight.

In five years, he and his partners bought more than 300 acres of farmland to build the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The facility needed a big race, so the company debuted the Indianapolis 500 in 1911. But Fisher had eyes on even bigger dreams.

In 1913, he sold his headlight company for $9 million, which equates with $215 million of purchasing power today. Now he had the wealth for a new project, a highway that would cross the U.S. from east to west, from New York City, New York, to San Francisco, California, from Times Square to Lincoln Park. And he wanted it done in time for the 1915 Panama-Pacific exposition in San Francisco. A bold idea, to say the least.

Fisher’s 3,300-mile highway utilized existing thoroughfares, which eliminated the need for road construction. With most of the roads being nothing more than dirt, road improvements—laying gravel or pouring concrete—would come later. He estimated the price at $10 million.

Fisher unveiled his idea in September 1912. Within a month, he had raised more than $1 million from celebrity contributors who included Thomas Edison, Theodore Roosevelt and President Woodrow Wilson.

On October 31, 1913, the Lincoln Highway was dedicated as the first national memorial to President Abraham Lincoln. At the christening, a group of supporters formed the Lincoln Highway Association. They put up road signs and published guidebooks, like a 1916 guide that advised readers to view the drive as “something of a sporting proposition,” one that required between 20 and 30 days to drive the entire route—at an average speed of 18 miles per hour.

To meet the needs of these newfound travelers out West, enterprising citizens offered their cabins or homes for folks to stay in, cheaply, with a place to park their cars overnight. Thus, the motel industry was born.

Pushed by Fisher and other organizers to finish the roads of the Lincoln Highway, most state and local governments complied because of the money visitors were spending in their areas.

The final price for it? No one is certain, although it exceeded the $10 million Fisher had predicted.

With the highway on path to be finished by the early 1920s, Fisher turned his attention to another road project—one that would run from northern Michigan to southern Florida. His Dixie Highway, dedicated in 1914, sparked a boom in travel to Florida, especially in the winter. As a prime developer of what became Miami Beach, he cashed in.

Of course, those highways were the precursors of modern interstates. Fisher would have loved them, driving 65 miles per hour to so many spots across America. Nothing like fast speeds for long distances.