Jesse James stands on a frozen pond. Through the ice, he can see the carp swimming inches below the surface.

Jesse James stands on a frozen pond. Through the ice, he can see the carp swimming inches below the surface.

He asks his friend if he ever entertains thoughts of suicide as Jesse empties his revolver into the ice, possibly shooting at the fish, possibly not.

Jesse’s murder at the hands of the young Robert Ford, an apprentice highwayman from a neighboring county who hoarded souvenirs and dime novels about the thrilling exploits of the infamous James Gang, is only a few months away.

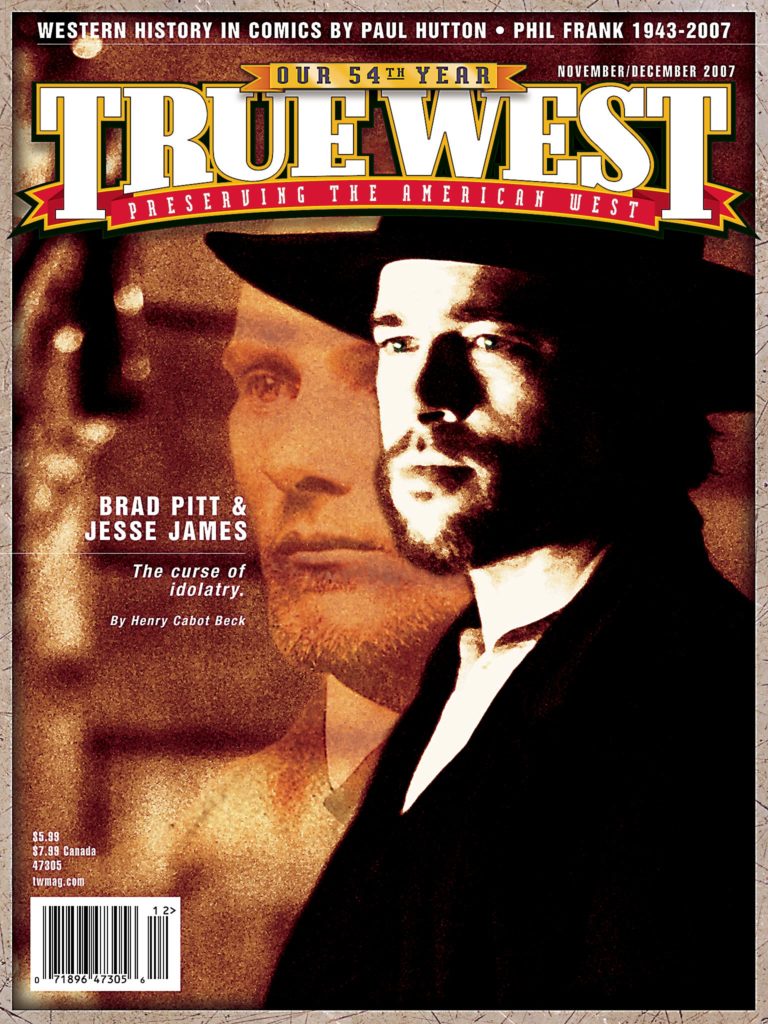

The Assassination of the Outlaw Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is an elegant and unsettling movie about a dance between a stone cold killer who is teetering on the brink of madness and the whelp who worships him.

“When Robert Ford killed Jesse, he got everything he wanted,” Casey Affleck says. “He got the notoriety. He got the fame. He became an outlaw, a gunslinger. He took down the big scary guy. He was more recognizable than the President of the United States. He got it in spades, exactly what he wanted. But he had no idea what it’d really be like.”

Affleck plays Ford, opposite Brad Pitt as Jesse James, in the film based on Ron Hansen’s novel of the same name. The movie belongs to Affleck and to Ford.

“Had he actually been able to really see Jesse when he was around him, he would have known better. He would have said, ‘This guy has everything that I want, and he’s miserable. Maybe I should think twice about what I’m getting myself into.’”

“The film picks up at the last year of Jesse’s life,” Pitt says, “and [Jesse] was certainly coming from a place of great paranoia, most of it justified.

“It’s also true to say he was a ruthless killer long before the film starts.”

When we first meet 19-year-old Ford, it’s September 1881. He and his brother Charley are recent recruits in the latest incarnation of the James Gang, and they’re about to rob a train. Nobody can possibly know that this will be the last train robbery for the James Gang, that Jesse James is drawing on his reserves to keep his hand in and his name alive, and that he’s beginning to unravel.

“When I read it, I thought, this is somebody who’s created his own reality,” Affleck says. “He was acutely aware of his own image in the public, and he wanted to be really well known, wanted to be the scariest guy, the baddest outlaw, and he was. This is a guy who would rob trains and leave a press release on the train for the newspapers to print.”

But the war that provided Jesse with lessons in thievery and wholesale slaughter is 16 years finished. Most of Jesse’s new gang members are too young to have ridden with Quantrill, Bloody Bill Anderson and the rest of his old bushwhacker buddies. The disastrous Northfield, Minnesota, raid of 1876 put the Youngers and the rest of his gang in coffins or behind bars when the townspeople rose up and took the gang apart. Now, even Frank, his brother, has left the gang.

“You know, and this is more of a current analogy, it’s kind of like the Rolling Stones breaking up,” says producer Jules Daly, “a band of men that has been so tight together; and they’re like brothers, and they would do anything for each other. That starts to fall apart, and that’s when Jesse’s paranoia sets in.”

At the same time, the noose is getting ever tighter and the government is more determined than ever to take Jesse down, offering rewards and deals for his capture or death.

“At that time, Missouri was called the robber state,” Affleck says. “People would go around it, avoid the area altogether, on their way west, which added days and days to their traveling time. This is why the governor’s so eager to catch him … ‘cause it was ruining the economy of the state, giving it a bad name. [Jesse] wasn’t a hero to the state; people hated him, and wanted

to get rid of him. They were scared of him. That’s why they were pressuring the governor. He couldn’t get re-elected if James was on the loose.”

Jesse’s friends are scared of him as well. We see the long chill of the fall and winter in the movie and James, more than ever convinced that he’s being plotted against, rides his friend Ed Miller (Garret Dillahunt) out into the fields and murders him.

“By all accounts, Ed was a really brutal fellow,” Dillahunt says. “But not that bright a bulb. So I think you see in Ed, who can’t compete mentally with Jesse—I kind of came from the tack that Ed had done nothing wrong to Jesse, and it seems to me that he was as much at a loss as anyone for why Jesse had focused his ire on him—[Ed] didn’t have the brains for any kind of plot. It makes him pretty pitiful, when he dies.”

The death of Ed Miller only serves to push Jesse’s friends even farther away from him and closer to the law.

Jesse and his wife and two children move to a new house in St. Joseph, Missouri, that sits high, for a safer view.

He invites Charley Ford, and later Bob, to move in. He eventually gifts Robert Ford a handsome new revolver.

Jesse then finds the newspaper that Bob has badly hidden, which features an article on the front page about how Dick Liddil, one of Jesse’s better friends, surrendered to the police.

In the film, we see Jesse making a very elaborate show for Bob of removing his sidearms and laying them out. He turns his back to fix a picture, and Bob kills him.

“My thoughts are, Bob is thinking, we’ve got no choice,” Dillahunt says. “He’s coming for us. And sometimes, that’s all you need to be courageous. Well, I’m gonna die if I don’t, I might as well try to end this thing. And in the meantime, why not become famous myself, become a hero, and then, gosh, that didn’t work out too well [laughs].”

Did Jesse James put his head on the block for Ford?

“This is the thing that historians argue over,” Pitt says, “because there were two curiosities about this last time, and that was the fact that he gave the gift of the gun to his would-be assassin, the very gun that would kill him days later, and that he also took his gun belts off at the moment or at what became the moment of the assassination, which he normally never did. So the two theories are one, that he had full knowledge of what Robert Ford or the Ford brothers were capable of and were after, and was taunting them and was going to take them out at a later time and kill them, and it was a bad gamble and a gamble he lost. The other argument is that he was unhinged, that he was weary of this life on the run and that it was actually a puppeteered suicide, unconscious or conscious. It remains ambiguous and I couldn’t pretend to know.

“I actually played it both ways, different takes, and let Andrew shape it in the editing.”

A third, more intriguing theory may fit.

Jesse’s notoriety was fully locked into place even before he died. His death seemed to seal him in mythic amber, always robbing trains, always hitting banks, always dying at the hands of the “dirty little coward.” For a guy who was, by all accounts, obsessed with his own presence in the public’s mind, he could hardly have devised a better demise. As it has often been said of those who have died when their spotlight was on the wane, death can be a pretty good career move.

If Jesse James believed that Bob Ford coveted his fame, what better way to assure him of a lifetime of infamy than as the “dirty little coward who shot Mr. Howard and laid poor Jesse in his grave?”

Maybe it’s a stretch. Okay, it’s a stretch. But sweet revenge on his killer from the grave, and a place in history that has so far extended 125 years and is still generating interest and controversy and big fascinating entertainments like this one. Not too shabby an ending.

The movie has a limited release in New York, Los Angeles, Austin and Toronto on September 21. Whether it will be released in theaters nationwide is yet to be announced.