Just as the Colt revolver and the Winchester rifle are icons of the post-Civil War West, one gun symbolizes the era of the fur trade.

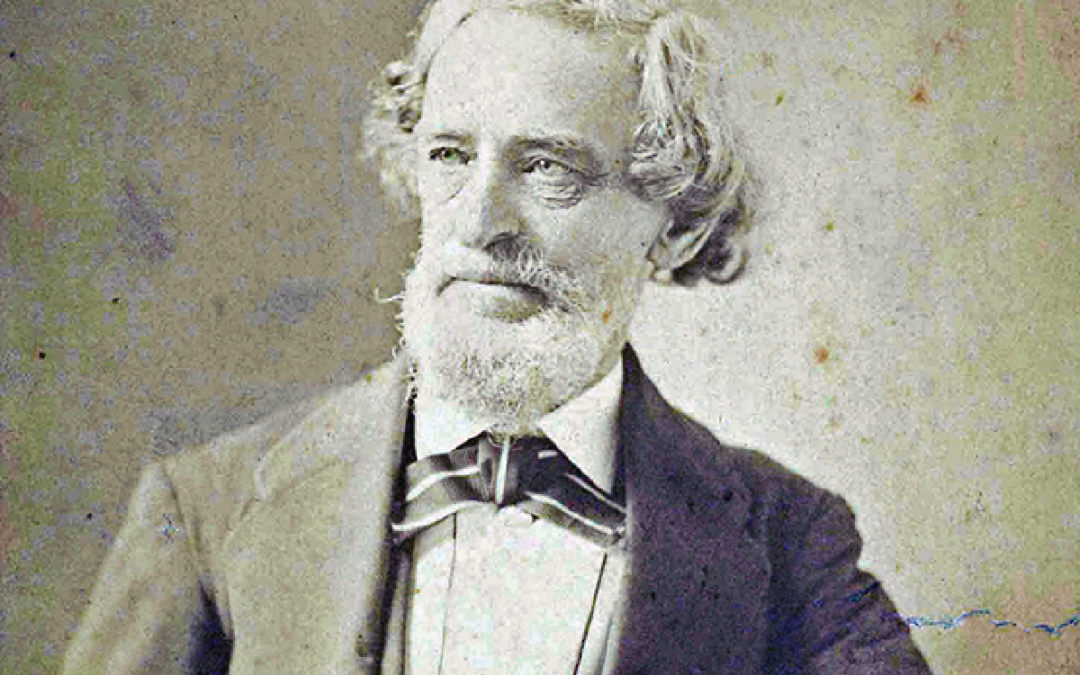

Courtesy Missour Historical Society

The rifle was the primary weapon for sustenance and defense with the early trappers and explorers in the American West. Although specific firearms makers are seldom mentioned in accounts left by these frontiersmen, we do know they initially carried the delicately fashioned, eastern flintlocks. Guns like the graceful, brass-fitted, Kentucky long rifle (44 to 46 inches in length) style with slender curly maple stocks and bore sizes of around .40 to .45 caliber, or the slightly heavier and simpler, unadorned (or iron-mounted) walnut-stocked .45 to .50 caliber southern or Tennessee rifles were the norm. It wasn’t long though, before they discovered that these smaller caliber guns were inadequate for the big game encountered in the far West, especially for longer-range shooting which was common in the Western mountains and plains. Gradually, these long rifles were modified by shortening and strengthening with a thicker stock, stronger lock, reboring the barrel or replacing it with a shorter, heavier one of .50 or greater caliber.

In the burgeoning Western fur trade, the most convenient jumping off locale for these trans-Missouri River traders was St. Louis, which had become the center of all business involved with the frontier. A number of gunsmiths were prospering there, largely through the Indian trade, and by modifying and repairing eastern guns to meet the demands of the rugged mountains. One of them, Jacob “Jake” Hawken, a gunsmith who arrived in St. Louis in 1807, eventually opened his own shop on Main Street in 1815 and by 1819 was evidently partnered with gunsmith James Lakenan. By 1825, with the death of Lakenan, Jake’s younger brother Samuel had joined up with him, resulting in the J. & S. Hawken partnership, which lasted for the next 24 years.

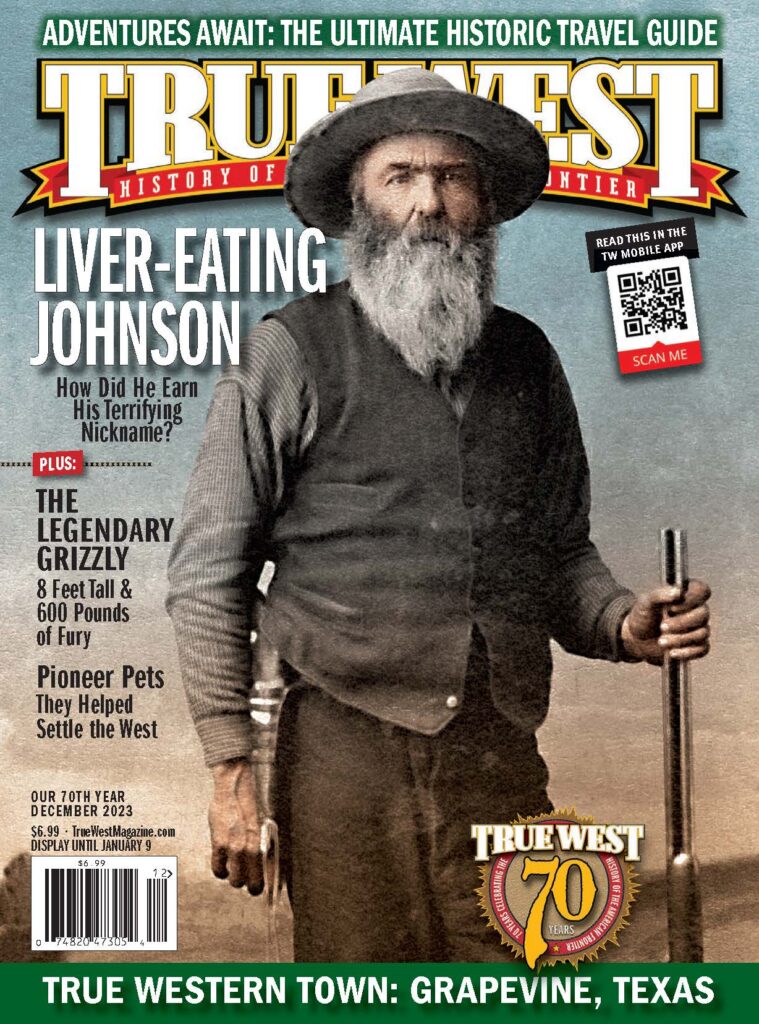

The timing and location was perfect for them, since their partnering coincided with the beginnings of the Santa Fe trading and the founding of the major fur companies Ashley & Henry Fur Company, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, the American Fur Company and others. Initially the brothers kept busy working on individual customers’ rifles. They’d shorten and strengthen their older longrifles to suit hard usage in the West. Ultimately, the brothers began supplying their own unique big-game rifles to the large outfits, as well as individual “free” trappers. Although these “Hawkins” (as they were referred to in several written accounts of the period) were not necessarily better than other rifles of the era, their ruggedness, uniform workmanship and performance soon earned the brothers a reputation as makers of fine “mountain rifles.” The Hawken rifle became the hands-down favorite of frontiersmen like Christopher “Kit” Carson, Jim Bridger, James P. Beckwourth, Jedediah Smith, Hugh Glass and many other mountain men, scouts and traders of the early West.

The early Hawken rifles were believed to be flintlocks with full-length stocks, but without any maker’s stampings, positive identification is difficult, and no guns have turned up that can be definitely verified as Hawken-made. There is a bit of controversy as to whether Hawken ever made flint arms, but many arms scholars believe that quite a number of them were indeed produced, and numerous records of purchases from the Hawkens by these major fur traders as early as the 1820s offers evidence of Hawken rifle production. Due to the hard use and primitive circumstances they endured, coupled with the early timing of their service life, few if any have survived. In the last decade, a heavy mountain rifle that’s been converted from flintlock to percussion and bearing J. P. Beckwourth’s verified engraved signature under the barrel has been found that has the earmarks of what would make an early Hawken…and Beckwourth was known to have favored Hawkens from their earliest production!

It’s believed that Hawken began turning out percussion rifles most likely in the late 1830s, and by this time, with the exception of a few customer requests, the majority of Hawken rifle characteristics were fairly standardized for the rest of their production. When Jake Hawken died of cholera in 1849, Sam took over the business and stamped his guns “S. Hawken St. Louis” (although he reportedly kept the “J & S” lockplate and barrel stamping for a short while after Jake’s death). Sam ran the shop until 1862 when he sold it to employee John P. Gemmer, who eventually used his own stamping on his Hawken-style guns.

Original Hawkens we encounter today are largely post-1840 rifles, dating from those years through the 1860s, and saw most of their use out on the plains after the end of the fur trade in the mountains. Briefly, Jake, then J. & S. Hawken supplied the fur trappers with the hardy rifle they needed. The Hawken was the first muzzle loader specifically designed for long-range knockdown power on Western big game. When the beaver market plummeted in 1840, the year of the last Western Rendezvous, the Hawken continued to appeal to a new group of customers. These later produced S. Hawken front loaders, along with several other St. Louis-made, mountain rifle makers, turned out guns along the lines of brother Jacob’s simple, but classic Hawken. Great quantities of them were sold to the next generation of Westerners—the scouts, guides, meat hunters and other adventurers who opened the frontier. Hawkens and their like were now called “Plains” rifles, since they were primarily used out on the plains during the surge of westward emigration in the 1850s-70s. These new frontiersmen—and the Indians too—wanted that same powerful, long-range armament that had earned lasting fame years before in the Rockies. Even for a number of years after the introduction of metallic cartridge breechloaders like the .50-70 Allin conversion Springfield and the Sharps, the Hawken remained a frontier favorite.

Now celebrating its 200th anniversary, the Hawken rifle has become known as the Mountain Rifle, and possibly enjoys as much fame today as in its past with muzzleloading hunters and sport shooters, in a variety of configurations (some authentic to the originals, others take great license in shape and details). It’s no wonder the state of Missouri has recently passed a bill making the Hawken the official state rifle. When one thinks of the mountain man of old, it’s often in the image of a rugged and hard-bitten, buckskin and fur-clad trapper of the high country, cradling the classic old-time Hawken rifle in his arms…that’s a true icon.

Typical Hawken characteristics

A typical Hawken has an octagonal barrel measuring 11⁄8 inches or more across the flats, and could be 34 to 36 inches in length. Originally a browned barrel is held to the stock by a pair of keys. Bore sizes run “32 (round balls) to the pound” (.53 caliber), or greater. All furniture and mountings are iron. A plain darkened maple or walnut half stock with a raised cheekpiece on its left side and a somewhat thick wrist replaces the full-length stock of the earlier guns. The barrel is fitted with an underrib running from the fore stock to the muzzle and holds the ferrules for the ramrod or “wiping stick.” Guns are generally devoid of a patchbox or other inlays as seen on the Pennsylvania-style longrifles. It wears a crescent-shaped butt plate, a patent breech and double-set triggers housed inside a unique trigger guard with a curled tang. Buckhorn open sights are standard fare. The barrel or lockplate may or may not be stamped “J & S Hawken.,” or “S. HAWKEN ST. LOUIS.” Weight is around 10 ½ to 12 pounds.