July 2-14 1882

July 2-14 1882

John Ringo has decided to move to Tombstone, Arizona (he has been living in San Simon and Galeyville). He arrives in town and meets Editor Sam Purdy of The Tombstone Epitaph, who later writes of their talk: “He said that he was as certain of being killed as he was of living then. He said that he might run along for a couple years more, and may not last two days.”

Taking in the Fourth of July festivities, Ringo drinks heavily, carousing with his many pards. When Ringo rides out of Tombstone, several days later, he takes extra bottles of liquor for the road.

Two days later, the King of the Cow-boys is spotted at Dial’s Ranch, in the South Pass of the Dragoons, still drinking.

A veritable, moving, one-man feast, Ringo encounters Deputy Billy Breakenridge, who later writes of the meeting: “It was shortly after noon. Ringo was very drunk, reeling in the saddle, and said he was going to Galeyville. It was in the summer and a very hot day. He offered me a drink out of a bottle half-full of whiskey, and he had another full bottle. I tasted it and it was too hot to drink. It burned my lips. Knowing that he would have to ride nearly all night before he could reach Galeyville, I tried to get him to go back with me to the Goodrich Ranch and wait until after sundown, but he was drunk and stubborn and went on his way. I think this was the last time he was seen alive.”

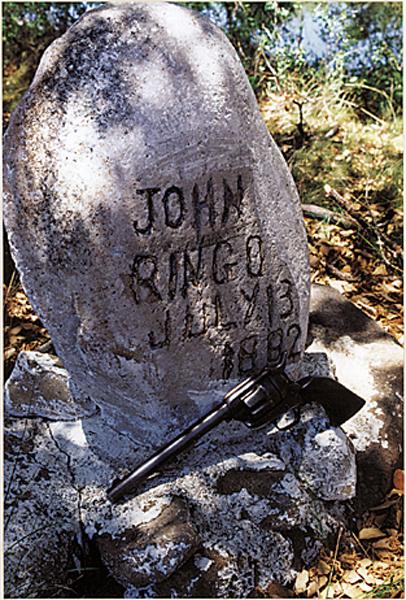

On the afternoon of July 13, not far from Rustler Park, Ringo’s horse gets away from him. He attempts to go after his big bay, but he doesn’t get far. A shot is heard at about three p.m. at a nearby ranch. John Peters Ringo’s body is discovered late in the afternoon on the 14th, by a teamster hauling wood. The body is found seated in “a bunch of five large black jack oaks growing up in a semicircle from one root, and in the center of them was a large flat rock which made a comfortable seat.”

A Hoodoo Warrior Cow-boy

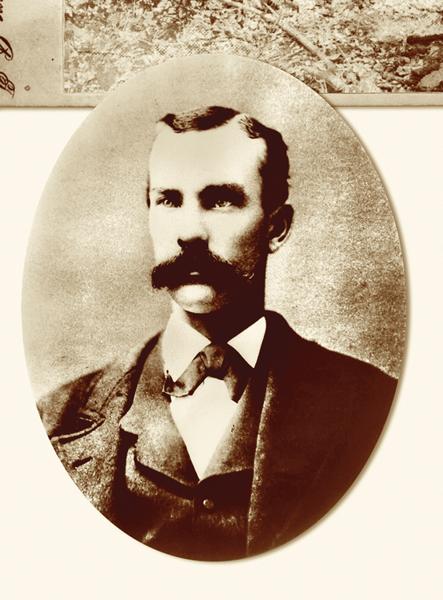

Originally from Indiana (b. 1850), the young John Peters Ringo lived for a short time in Missouri, before his family packed up and headed for California. While crossing through Wyoming, his father accidentally shot himself with his own shotgun and was buried along the trail.

After a stay in San Jose, California, John left his mother, brother and sisters in 1870 and gravitated east to Texas, where he ultimately made quite a name for himself in the Hoodoo War (an ethnic-cattle feud in the Mason section). Indicted for one killing and reportedly involved in several others, he came out of Texas in the late 1870s with a reputation as a notorious and dangerous man.

Ringo landed in Arizona in 1879 and described himself as a “speculator” in the 1882 Cochise County Great Register. After shooting a fellow drinker over his choice of liquor (his only known shooting in Arizona), Ringo took up residence in San Simon but also stayed in Galeyville, where he held up a poker game (resulting in the third formal charge against him).

He missed the Fremont Street fight with the Earps and Doc Holliday, but tried to make up for it two months later in a failed showdown on Allen Street. At the time of his death, Ringo was one of the most well-known men in the territory and considered by the press to be the leader of the cow-boys.

While some who knew him could not believe he would take his own life, many others claimed Ringo “frequently threatened suicide.”

The Ringo “Mysteries” Examined

In his book Johnny Ringo, author and researcher Steve Gatto examines the so-called mysteries surrounding the King of the Cow-boys’ demise. Here they are with Gatto’s conclusions:

• Mystery No. 1: Ringo had torn up his undershirt and wrapped pieces of it around his feet, the theory being that Ringo’s bay horse had wandered off and he started off on foot to search for him. His boots began hurting him, so he pulled them off and made “moccasins of his undershirt.” “Crazed with thirst” and far from help, Ringo gave up, sat down and shot himself. The facts: According to the coroner’s report, Ringo had “travelled but a short distance in this foot gear.” And he was found within spitting distance of water (200 feet) and “not more than 700 feet from Smith’s house.” Also, “The inmates of Smith’s house heard a shot about 3 o’clock Thursday evening,” and it is believed this is the lone shot that ended Ringo’s life. The lone shot also argues against a gun battle, as described by Wyatt Earp, wherein he claims after a protracted exchange of gunfire, Earp got Ringo with a lucky shot at 75 yards (also unlikely given the trajectory of the death wound, which was upward at a 45 degree angle between the right eye and ear).

• Mystery No. 2: Found on Ringo’s body were two cartridge belts, but the belt for revolver cartridges was “buckled on upside down.” The conspiracy theorists believe that Ringo’s killer(s) put the belt on upside down to humiliate him, or make a point. The facts: Ringo was on an extended drunk and possibly put his belt on incorrectly, and who’s to say, he didn’t do it on purpose?

• Mystery No. 3: A small part of the forehead and scalp was gone, including some hair, which the coroner’s report said appeared as if “someone had cut it with a knife.” The facts: Even if someone had taken hair as a sort of trophy, it doesn’t mean Ringo was murdered. It’s possible John Yoast, the man who initially found Ringo, took the hair as a souvenir.

• Mystery No. 4: There were no powder burns on Ringo’s temple, suggesting that he was shot at a distance. The facts: The coroner’s jury made no mention of the absence or presence of powder burns. Plus, Ringo’s body had been lying in the hot sun and was decomposing rapidly and “had turned black.” The men were more concerned with burying the body. It probably did not occur to them that more than a century later, people would be debating the particulars of their descriptions.

In Conclusion:

“I showed [Yoast] where the bullet had entered the tree on the left side. Blood and brains [were] oozing from the wound and matted his hair. There was an empty shell in the six-shooter and the hammer was on that. I called it a suicide fifty-two years ago, I am still calling it suicide. I guess I’m the last of the coroner’s jury.”

—Robert Boller, 1934

Evolution of a Legend

How did a self-described “speculator” and hard drinker, with a modest record of “kills” or gunfights, become one of the most famous names in the annals of Old West gunfighters? A trail of hyperbole gives us a clue:

“During the past few years thirty-two men dared to doubt his honor. They now fill thirty-two graves … although he had many competitors in his line, he had no true rivals, and Curly Bill and Billy the Kid will not bear comparison with him.”

—Grant County Herald, July 22, 1882

“Ringo was a mysterious man. He had a college education, but was reserved and morose. He drank heavily as if to drown his troubles; he was a perfect gentleman when sober, but inclined to be quarrelsome when drinking. He was a good shot and afraid of nothing, and had great authority with the rustling element.”

—Billy Breakenridge, Helldorado, 1928

“John Ringo stalks through the stories of old Tombstone days like a Hamlet among outlaws, an introspective, tragic figure, darkly handsome, splendidly brave, a man born for better things, who, having thrown his life recklessly away, drowned his memories in cards and drink and drifted without definite purpose or destination.”

—Walter Noble Burns, Tombstone, 1927

“John Ringo was a man with whom everyone in that part of Arizona must reckon, the fastest gunfighter and the deadliest, a man who courted trouble, with the thoughtless courage of a bulldog.”

—Eugene Cunningham, Triggernometry, 1941

“John Ringo’s image was created for him by inaccuracies of innumerable writers, and I?believe that he remains a western figure largely because of the mellifluous tonal quality of his name.”

—Jack Burrows, John Ringo: The Gunfighter Who Never Was, 1987

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

In the 1920s, Wyatt Earp began telling a series of writers, including Forrestine Hooker, Frank Lockwood and Frederick Bechdolt, that he had waylaid and killed John Ringo as Earp and his Vendetta posse were on their way out of Arizona in March 1882. Earp even drew a diagram of the fight. The problem with this claim is that Ringo died in July, almost four months after Wyatt had fled the state as a fugitive.

This hasn’t stopped some Earp buffs from fantasizing that both Wyatt and Doc Holliday snuck back from Colorado, where they were known to have been in July 1882, and assassinated the cow-boy leader. Even this strains credulity when one considers that Holliday, at least, was in court in Pueblo, Colorado, two days before Ringo’s death.

Buckskin Frank Leslie reputedly was the first to take credit for the death of Ringo. While in Yuma Prison for the murder of his wife, Leslie allegedly confessed to a guard that he killed Ringo. Few believe him.

Another name attached to Ringo’s demise has been Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce (Michael O’Rourke), who supposedly ambushed Ringo near the latter’s camp in the Chiricahuas. Why? O’Rourke got “scared up,” said Fred Dodge, a Tombstone resident at the time, who shared his story with author Stuart Lake. This version has even less adherents.

Recommended: Johnny Ringo by Steve Gatto, published by Protar House.

Photo Gallery

– All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell –

—Tombstone Epitaph July 18, 1882

– All Photos True West Archives –

The days went by, he mended fast

Then from the dawn till setting sun

He practiced with that deadly gun

And hour on hour I watched in awe

No human being could match the draw of Ringo

—Lorne Greene, “Ringo,” 1964