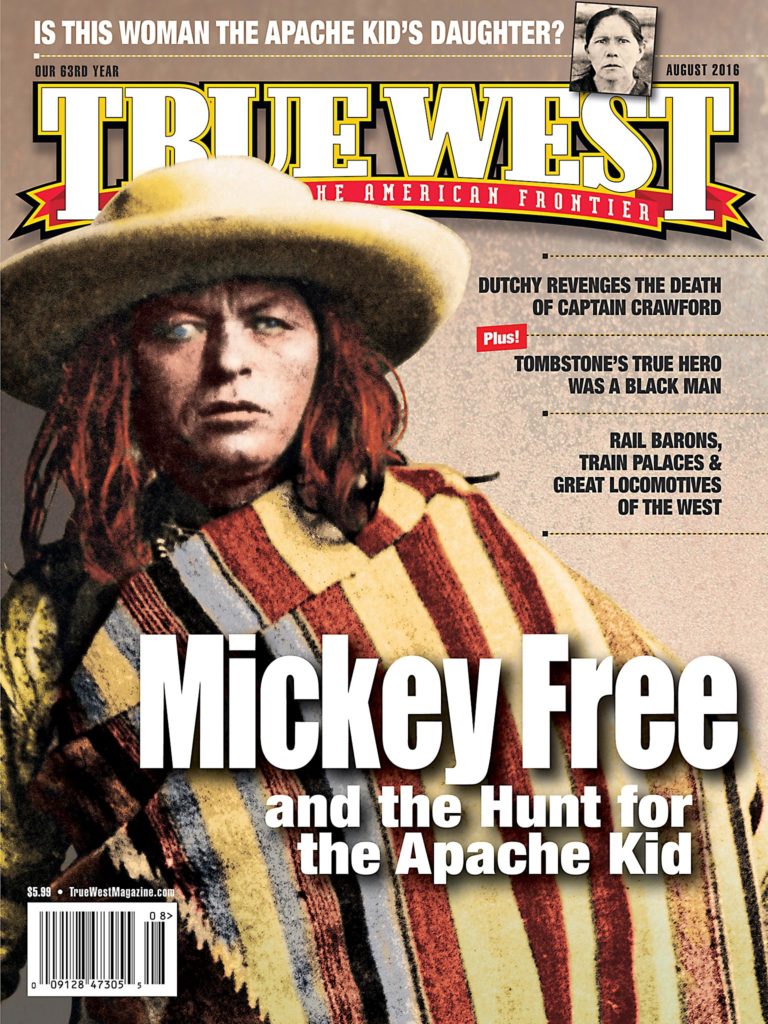

Prologue

PROVING GROUND

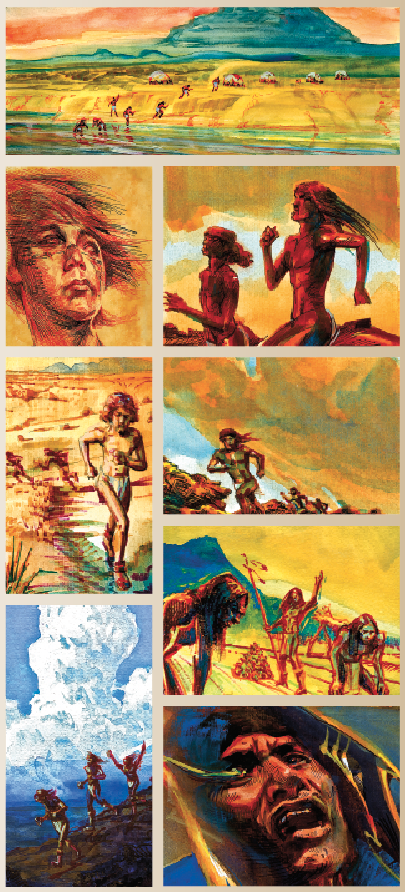

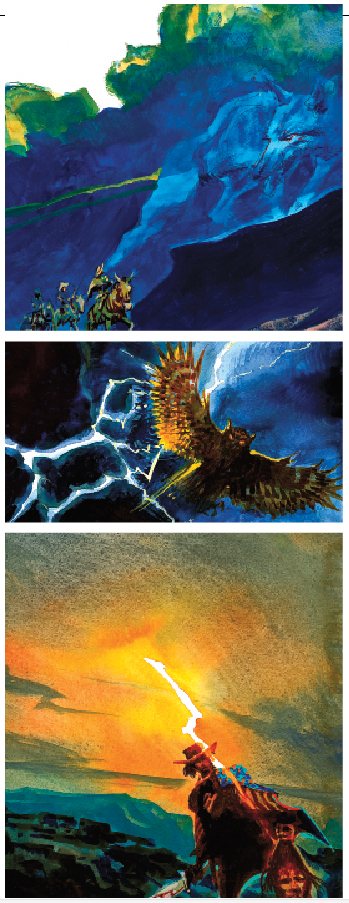

The boy is emaciated. His mop of red hair hangs across his scarred face, obscuring a lost eye. He staggers and stumbles up the narrow mountain trail. Other boys are already coming down it. They pass him as if he does not exist. He wants to speak, but dares not open his mouth. Breathing comes hard. He is determined to stay strong, but he still has so far to go. He wants desperately to prove himself worthy of the name Apache.

The boy is emaciated. His mop of red hair hangs across his scarred face, obscuring a lost eye. He staggers and stumbles up the narrow mountain trail. Other boys are already coming down it. They pass him as if he does not exist. He wants to speak, but dares not open his mouth. Breathing comes hard. He is determined to stay strong, but he still has so far to go. He wants desperately to prove himself worthy of the name Apache.

The task is simple. Each boy training to be an Apache warrior must gather at the river bank at dawn, take a gulp of water and hold it in their mouths. Then the entire group runs toward the blue ridges of the Graham Mountains. It is not only a race, for the goal is to snatch the first pinecone they can find, return to the river and drop it at the shaman’s feet. Then they spit out the water.

Southwestern frontiersman Jim Young was digging graves at the Holy Hope Cemetery in early 1935 when a cub reporter for Arizona’s Tucson Citizen located him.

Gravedigging was a sorry profession for a former slave who once served as bodyguard and right-hand man to “Texas” John Slaughter. But no one remembered the old days now, and a man had to make a living any way he could, even if his years numbered 102.

After the reporter asked Young about his Tombstone years, when he knew Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, Young landed on one of his favorite stories. “To the old-time Apache, mercy was not a virtue,” he said. “That’s why the Mickey Free story is so strange to me.”

With that, he launched off on this wild tale of the true fate of the Apache Kid.

“Tom Horn and I left Slaughter’s ranch at first light. Our plan was to stake out the spring where I had seen the Apache Kid and wait until he came in for a drink and nab him. We watched that spring like a hawk all day, but no Kid.

“Finally, in the wee hours, I noticed a dark figure darting along the arroyo. Horn pulled up his Winchester and tracked the shadow. I kept whispering for him to hold his fire, but I just sensed he was going to shoot. I finally grabbed his rifle barrel and said, ‘You’re going to shoot a woman!’

“You would have thought he would have thanked me, but he cussed me out something fierce. I was right, though. It was a woman. I also had my suspicions she was with the Apache Kid, but we’ll never know, because they both got away while I was getting a tongue lashing from Mr. Horn. And let me tell you, that ol’ boy could swear like a Mexican mule skinner. He called me the son of a ‘double-whore mother’ and other oaths that combined my relatives to members of the animal kingdom, and which I thought were pretty imaginative, but later, when we got deeper in the Sierra Madre, I discovered they wasn’t all that original.

“Me and Horn were on the chase for the money, but Free was after something else, and that puzzled me.”

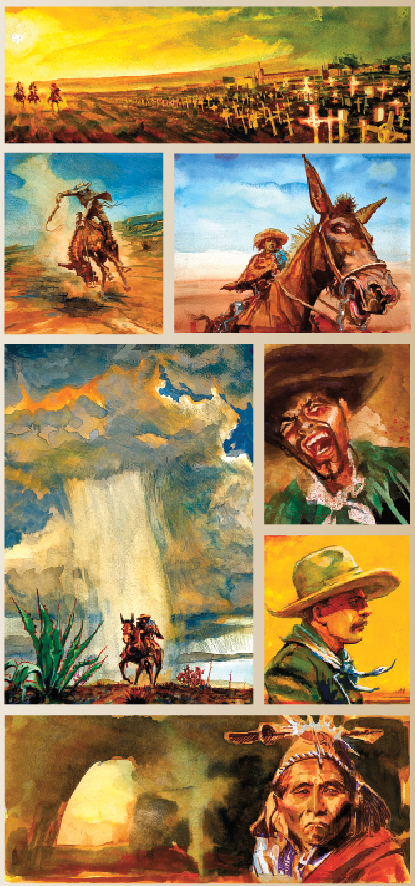

ENTER MICKEY FREE

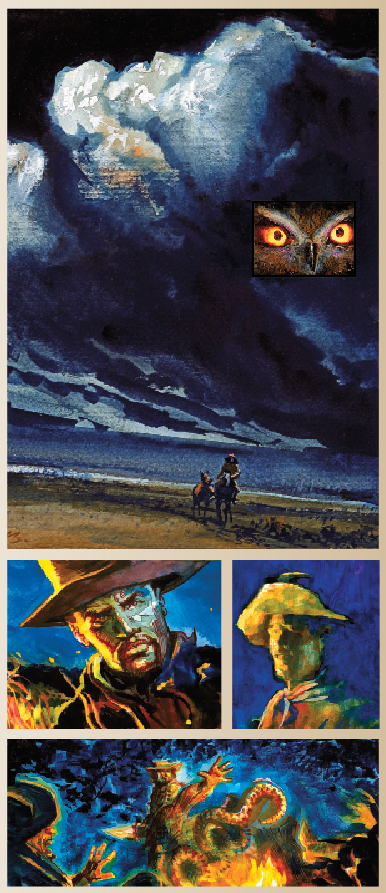

“We moved on down to the Bavispe River the next day, and Free joined us that night,” Young told the reporter. “I don’t know how he found us, since we were covering our tracks. First, we heard an owl screech, and then, Mickey emerged from the shadows and tossed three rattlers on the fire. That was an entrance I will never forget. Mickey called it good fun, but we had a heck of a time getting down from the trees we jumped straight up into.

“Mickey laughed and used his machete to skin those rattlers. Then he roasted them on a spit. Horn and Mickey had them for dinner, but I took a pass.

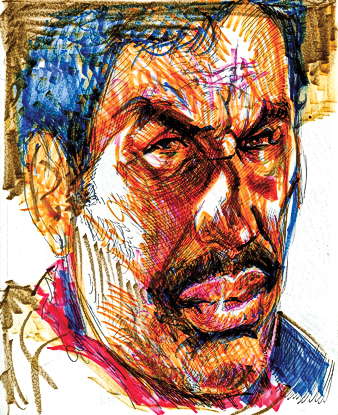

“Mickey was like a dust devil—and he was skinny as a pick handle. Plus, he looked crazy with his ghost-like eye. The way he leered at you spooked everybody, me included. He rode a mammoth jack mule, 16 hands high. Every morning on that trip, Mickey and that mule fought each other for dominance; it was about a 50-50 chance which one of them would prevail. The Mexicans called him ‘Mickey Mula.’ Horn, meanwhile, couldn’t stand mules. A horse, he said, ‘is a noble animal, while a mule will wait its entire life for the opportunity to kill a man.’

“Of course, Tom Horn and Mickey went way back, and so, after they feasted on those rattlers, we settled back and poked the fire, and the war stories flowed. They talked about various adventures, and Horn kind of opened up. Horn talked about problems he had encountered in Wyoming, but he didn’t seem all that concerned. ‘I’ve done my job on the square,’ he said, ‘and I’m confident they’ll protect me.’ He didn’t say exactly who would protect him, but in Arizona, the U.S. Army protected both Horn and Mickey. In fact, the Army trained those boys to be killers.

“I asked Mickey just how well he knew the Kid. He said they grew up together in the Aravaipa Canyon country, and they had once been best pards. This struck me as odd. If the Apache Kid and Mickey were like kin, why was he even on this hunt?

“He thought about my question for some time. He finally looked at me, with that sideways stare of his, and said: ‘Pinecone.’ That was it. He never said another word about it.

“Well, nearly 50 years passed before I figured out what he meant, but in the end, that word was the key to the Apache Kid’s fate.”

ON THE HUNT

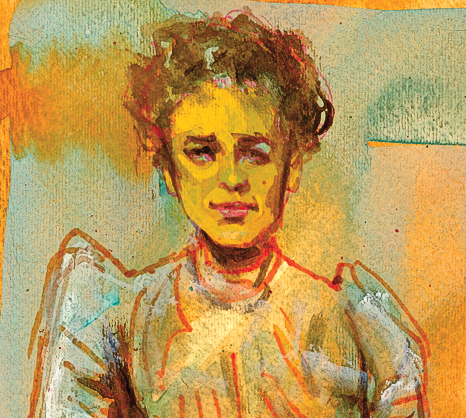

“In the morning,” Young continued, “the three of us hit the trail. A lot of Mormons lived in Mexico back in those days. We came upon a small Mormon wagon train, with seven women and two men. One of the young wives was quite the looker, and I’ll never forget her name: Hannah Hood Hill. She gave us homemade biscuits and lemonade. Those were the best biscuits I have ever eaten in my life. We were all smitten with her, but Horn most of all. For the rest of that trip, when the going got tough, Horn would joke, ‘You two go on, I’m going back to find Hannah Hood Hill and settle down.’

“The Mexicans didn’t fret over how many wives a man had, like folks up in the States did. It was live and let live with them. I think it was Porfirio himself who said, ‘It makes no difference to Mexico whether you drive your horse tandem or four abreast.’

“About noon, we saw we had someone on our back trail. We could tell, even from a distance, they had no good intent. Somebody later told us they were a Durango outfit led by a bandido with the unlikely name of Doroteo Arango. Horn laughed: ‘What kind of a bandit name is Dorothy?’

“As they closed the gap on us, I was braced for a bullet at any moment. Horn declared, as if we were putting on a performance in the Bird Cage, ‘They have come upon us!’

“At 100 yards out, them boys behind us opened fire. I heard the first ball whizz right by my ear. Whatever it started out as, it was a shootin’ match now.

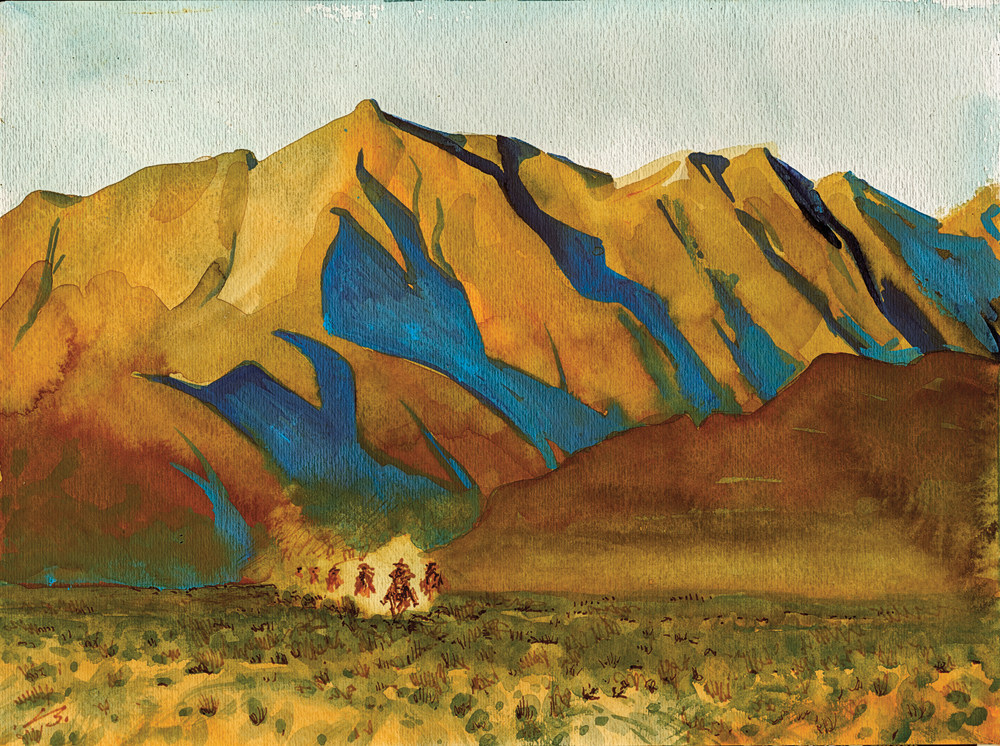

“Between us and safety was nothing but bald desert, and it looked to be a two-mile run to reach cover. We all spurred our mounts and, with a ‘Heee-Yaaah!’ we taken out of there like hell-chasin’ tanbark.

“Halfway across the flats, Mickey reined in and let us pass. Then he turned that big jack around and went straight into the teeth of those riders. I think the move unnerved the attackers; the lead riders veered off and headed for the wings. Mick pulled his pistol and fired rapidly as he rode on, with the reins in his teeth. The rest of the gang quickly followed the leaders who were fleeing from us, and, in no time, we saw their dust on the horizon.

“When Mick rejoined us in the rocks, he was smiling like a jackass eatin’ prickly pear. That boy and his mammoth jack sure loved to mix it up with anybody who would give him a go. Damned if that jack mule wasn’t smilin’ himself.

“At dusk, we made a dry camp, and I took care of the mounts, rubbing them down and sponging out their mouths with water from my canteen. Horn told me I was wasting good water, but I knew better. He was from the cowboy school —ride ’em ’til they drop, and then get another one. I was schooled in Kentucky, where a little gentle treatment goes a long way for horses, or men.

“The night came on, soft and dark. A cool wind blew up from somewhere, and it felt good. We were bone tired, but we were so worked up, none of us could go to sleep. Mickey finally said, ‘Somewhere in these canyons, we know the Kid is looking up at the same stars.’ ‘So?’ I asked. ‘That is strong medicine. Put yourself in that place.’

“Mickey sat up, closed his eyes and craned his neck in a circle. He said he could feel the Kid close by. Then he laid back and went to sleep and immediately started sawing logs.

“When we got up the next morning, Mickey was gone. Horn just shrugged: ‘He’s up to his old tricks. He’ll show up when we need him.’ Sure enough, out on the trail to Nacori Chico, Horn found a pile of stones, which is the Apache way of creating a road map. It was just a pile of stones to me, and I wouldn’t have even stopped if Horn hadn’t held up his hand. Horn rode around the stones, then pointed us south. So, off we went, trying to find our guide in that godforsaken country.

“Ten miles farther on, Mickey left us another ‘monument,’ which pointed us off the main trail toward who knows where? We blindly took that cow trail. Horn shrugged sheepishly and said, ‘Mick knows where he’s going.’ I wasn’t so sure, but I didn’t have much choice in the matter, so off we went.

“We finally caught up to Mickey sitting pretty in the middle of a large caravan of horses, donkeys, mules and scientists from Norway. Mickey had his feet up on a barrel of honey, and he was sipping tea with Carl Sofus Lumholtz, who was headed for the Sierra Madre to try and find the answer to what happened to the folks he called ancient cliff dwellers. Sounded just like another bunch of Indians to me.

“Lumholtz and his eight scientists were quite taken with Mickey and were treating the boy like a royal specimen. Being gentlemen and scholars, they treated us as well, and we ended up having a grand dinner of plump quail and a port champagne. We spent the night there in style.

“In the morning, we said our goodbyes and moved on down the trail. I didn’t realize then where that connection with Lumholtz would lead me—to the answer of what happened to the Apache Kid. Life is so connected that way. When you pull one strand…

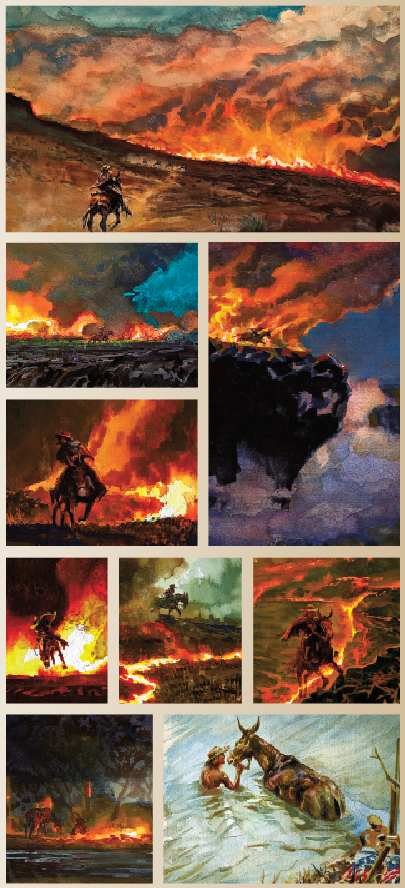

FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN

FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN

“West of Fronteras,” Young told the reporter, “we met some freighters on the road, and they warned us of a big fire up ahead. Sure enough, when the road crossed a dry lake, we met a wall of people fleeing the flames. The ricos came first, in their fancy carriages, followed by red-eyed Mexican cattle being herded by hard-eyed vaqueros. We gave them a wide berth. Behind the herd, a giant wall of dust enveloped us, and, as we rode by, we met all the straggling peons, choking in the dust. When we cleared the dust, we saw the flames. We felt the heat from the fire even at that distance, and we saw the puff of smoke and heard the whang of a Winchester borne slug that took a chunk of Mickey’s poncho with it. Mickey pulled out his Sharps, got down on one knee and let loose with his Big Fifty. We saw the dust jump off the jacket of the shooter as he reeled in the saddle and toppled to the ground. The rest of those cabrons rode toward the fire, as Mick and his mammoth jack went in hot pursuit.

“The outlaws disappeared into a seam of the fire as Mickey rode on, trying to get an angle on them. It was a trap, of course. The bandidos led Mickey into that fire, hoping it might kill him. As Mickey tried to swing wide and get around it, the fire jumped out ahead of him and, within no time, had sucked up the back trail. Mickey could not go back, so he rode on, into the teeth of the heat and the smoke.

“His mammoth jack saved him that day, as Mickey jumped through the flames, backed up against a cliff, where the flames were licking him good. We caught up with Mickey in the morning, when he was waist deep in the Bavispe River, soothing the burns on his jack. Me and Horn had a good laugh—because Mickey’s eyelashes were burnt off. We didn’t have the heart to tell Mickey.

“We were deep in the last stomping grounds of the free Apaches. In that back country, the wind blew like a curse. This was wild country, and the folks in it were even wilder still. I could feel it in my bones—still do.”

We crossed into the Quemado and plunged deeper into the darkness. Mickey kept looking at the clouds for signs, and Horn kept rolling his eyes. Twice more, we were ambushed by Arango’s bandidos, and twice, we beat them back. We knew eventually we were going to run into the Mad Russian, and we still hoped to bag the Kid and get out before that hard ridin’ Cossack got onto our trail.

“I was carrying a letter of safe passage, signed by Gen. Miles and the president of Mexico, Porfirio Díaz, assuring everyone we were buena gente, but we had a problem: on an earlier trip to Mexico, Mickey had shot and killed a corrupt rurale who was drunk and tried to pistol whip him. Horn claimed Mick pulled his ‘pistol in the poncho’ trick and dropped that cabron dead in his tracks. The problem was, the dead rurale was engaged to Emilio Kosterlitzky’s daughter (in fact, Mickey was at his bachelor party when the altercation happened), so we weren’t exactly looking forward to meeting the Mad Russian any time soon. Sometimes you get what you resist.

“Two days later, we were captured by the rurales while crossing the Bavispe River. When we were brought before the colonel, Emilio greeted us in perfect English: ‘Hang them!’

“We had the nooses around our neck when I finally managed to produce the letter of safe passage. Well, Porfirio was his boss, and we were spared, for the moment. That’s when we learned that Kosterlitzky claimed to have already bagged the Kid. When Kosterlitzky realized Horn and Free could identify the Kid, he took us as his prisoners to Magdalena so we could see the body and the evidence in person. Upon inspection, both Mickey and Horn agreed it was not the Kid. They recognized the dead Apache as Bachenal, one of the renegades who broke out with the Kid.

“The disappointed colonel showed us Sheriff Glenn Reynolds’ watch, which they had taken off the body. Emilio was not happy, but he decided to let us go. I think he intended to follow us to see if we would lead him to the Kid. He made us promise we would head for the U.S. in the morning.

“We camped just outside of town. For the first time, in a long while, we built a big fire and had a grand old time. I was curious about the watch and what it meant. Horn told the story: When the Apache Kid was liberated from the jail wagon on the way to the prison in Yuma, he had seven other Apache prisoners with him, who did all the killing. They stripped the bodies of the two lawmen and took Reynolds’ rifle, pistol and watch. Bachenal was the one who engineered the break, by slipping off his handcuffs, and he probably thought he deserved the watch. He was with the Kid when the rurales came upon them. Kosterlitzky had thought the watch would prove powerful evidence that the body was the Kid’s and allow him to claim the reward.

“The next morning, Mick was gone. Before we could break camp, here came Emilio, with a whole squad of rurales. The Mad Russian was indeed mad. He demanded to know where Free was. Horn shrugged and said, ‘Hell, we have no idea. He does this all the time.’

“‘He took something of mine,’ said Kosterlitzky, with some force, ‘and I want it back. If you are smart, you will find him and tell him to return it immediately.’

“We were puzzled. ‘Well,’ Horn finally said, ‘How will we know what to tell him to bring back if you don’t tell us what it is?’

“‘Just tell that little thief, he needs to return what belongs to me. He will understand.’

“We left pronto. Sure enough, about two miles out of Magdalena, Mick had left us an Apache monument, only this time, he also left a cryptic note under the bottom rock, which had three words on it: Zig Zag Canyon.

“Well, right then, we knew three things: Emilio and his rurales would be following us; whatever Mick had stolen from the Mad Russian, we were all going to pay for it; and, to my surprise, but not Horn’s, Mick had evidently broken the code of where the Apache Kid was hiding.

“Two hours later, we rode into the draw that led to Zig Zag Canyon. We saw Mick, in the top of a tall Cottonwood, watching the canyon with binocs. Seeing us, Mickey swung down from branch to branch, like some kind of ape man, and landed on his mule, which, of course, startled the jumpy jack. He began to buck, and the two of them rodeoed around us in a wide circle, until Mickey finally got him under control and reined in between us.

“Two hours later, we rode into the draw that led to Zig Zag Canyon. We saw Mick, in the top of a tall Cottonwood, watching the canyon with binocs. Seeing us, Mickey swung down from branch to branch, like some kind of ape man, and landed on his mule, which, of course, startled the jumpy jack. He began to buck, and the two of them rodeoed around us in a wide circle, until Mickey finally got him under control and reined in between us.

“‘Always with the big entrance,’ Horn said calmly. ‘You ever arrive anywhere without the drama?’

“‘Sometimes,’ Mick said, ‘but you’re not there, so it doesn’t matter.’

“We told Mickey, whatever he took from Emilio, he better move quick. Horn said he’d be surprised if the rurales didn’t show up at any minute.

“So we spread out and entered into the mouth of Zig Zag Canyon as evening came on.

“Mick was restless. He knew the Kid was near. At the end of the canyon was a series of caves that interconnected. As it was getting dark, we dared not attempt a frontal assault. We instead took up positions around the entrance, back about 500 yards to be safe and control the only means of escape. The plan was to wait until dawn and then attack from three directions.

“Around midnight, an owl swooped over our position and hooted loudly. When I turned to see what Mick thought of this bad omen, he was gone.

“Horn didn’t see him leave either. It was as if Mick had turned into that owl and taken flight. Of course, Apaches have a powerful fear of owls, the bringer of death, and maybe that owl had spooked Free.

“Not more than two minutes later, we heard the report of a long gun. Horn pegged it as a Springfield, but I thought it was a Sharps. Neither one of us wanted to tangle with the Kid in the dark of those caves, where we were certain he knew every single nook and cranny. We couldn’t believe that sound had come from Mickey; he would not be so foolish as to charge in there in the dark.

“We found the Kid’s camp in the morning, in the middle cave, and saw signs of a struggle and blood, but no sign of the Kid, the girl or Mickey.

“With both Arango’s bandidos and Kosterlitzky’s rurales in the neighborhood, we felt like our luck had run out, so we headed for the border. We were 12 days getting back up on the San Bernardino. We had another run in with Doroteo’s boys, but I’ll save that little skirmish for another time.

“When we got back to Arizona, we heard that Mickey had ridden into San Carlos with the Apache Kid’s head in a burlap sack. The Kid was identified by the distinctive headband attached to the head. I later saw it, and it was definitely the Kid’s. Sieber said Mickey also returned Reynolds’ watch, which cinched the deal. Knowing the true heritage of that watch, that made me wonder if something fishy was going on, but the Army called off the search for the Kid, and I let it go.

“Well, last year, a Norwegian feller came to Tucson looking for me. He had read about my adventures on the trail of the Kid in Carl Lumholtz’s writings. Helge Ingstad was his name, and he wanted to know if I could take him to Mexico and show him where Zig Zag Canyon was. It had been 40 years, but I got a compass in my nose, so off we went.

“It took us the better part of two weeks, but we located Zig Zag Canyon. The caves were still there, but not much else. Leaving that area, we met an old Mormon from Colonia Juarez who suggested we visit a ranch east of Nacori Chico. There, we found a woman by the name of Lupe, who some claimed was actually the Apache Kid’s daughter. Ingstad talked to her through an interpreter, and this is what she told him:

“She said her mother told her the story about hiding in a cave when an owl scared the girl’s father, the Apache Kid. He dropped his guard for just a moment, and Mickey Free used this diversion to get the drop on her father. She said her father was strong and quick, and he tried to overpower Mickey, but Free fired his big rifle and wounded her father. She said her mother grabbed a knife and tried to help, but Mickey disarmed her and dragged her to where the Apache Kid was laying on the ground.

“Both her mother and father thought Mickey was going to kill them. Instead, he demanded her father’s headband. When her father gave it to Mickey, he turned and started to leave. Her father wanted to know why Mickey was letting them go, and Mickey just smiled and said, ‘Pinecone.’

“She had heard that word before. Her father always told the story that when they were kids, being trained as warriors, they had to run up a mountain and come back with a pinecone. Her father was always first, and poor Mickey was always last. One day, Mickey said, ‘Some day, I am going to beat you and show you who’s boss.’ Her father knew why it meant so much to Mickey to win just once. It’s the Apache way. To make your point, and then let it go. Mickey had made his point. She said that is the story her mother always told.

“Then Mr. Ingstad said, ‘Ask her when her father died.’

“The translator listened to Lupe’s answer. Then he looked at Ingstad and me, and he said, ‘She says he didn’t die. He’s still out there.’

“So Mickey had tricked us all. He cut off Bachenal’s head, put the Kid’s headband on it and fobbed Reynolds’ watch, which all convinced the U.S. Army to call off the search, thus allowing the Kid to start a new life in the Sierra Madre. I saw Mickey do some bad things, but that’s all in the past. May God have mercy on the soul of Mickey Free.”

WHO LET THE DOGS OUT?

“Emilio Kosterlitzky told us the story of Glenn Reynolds’ watch,” Young told the reporter. “He and a small detachment of rurales were on the trail of a band of Gringo smugglers. They had followed the smugglers’ trail south from the international line. They seemed to be gaining on them when they suddenly came upon a scene of slaughter. The dead bodies of the smugglers were scattered about with their smuggled goods strewn among the bodies. They had not been dead long.

“The Apache trail was fresh, and Kosterlitzky set on it at once. The following day, the rurales crossed an immense flat that led to a rock-strewn outcropping perfect for an ambush. The Mad Russian had his wolf hounds. With his command, they set out on the trail to sniff the boulders ahead. It did not take the hounds long to find their prey. The rurales charged after the sound of the barking dogs, only to be met by a volley from the rocks.

“Two of Kosterlitzky’s men fell before the rurales drove the Apaches from the hill. Although several of the Apaches escaped, the rurales found three dead warriors. Kosterlitzky inspected the bodies, and from one, he retrieved an ornate gold watch. The watch was engraved with images of sheep and cattle, as well as the name Glenn Reynolds. Kosterlitzky did not recognize the body as being the Apache Kid’s, which perplexed him, for he had met the boy several years before and thought he would remember him.

“Back in 1886, in Guasabas, a group of Capt. Emmet Crawford’s scouts got roaring drunk, hurrahed the town and made unwelcome advances to the local ladies. Most of the men returned to Crawford’s camp, but Kid and a handful of the scouts remained and pretty much had the town treed. They ran off the local constable, who attempted to arrest them, but were soon confronted by the Mad Russian and six of his rurales who had ridden in from Bavispe. When the Apaches made a fight of it, Kosterlitzky wounded one of them, which caused the rest to bolt, and captured the Kid.

“Colonel Kosterlitzky thought it might be a good idea to execute his prisoner as an example to the other mansos, or tame Apaches, as the Mexicans called the scouts,for they had left a string of roasted Mexican cattle all along their trail from the Arizona line. Most of the locals were fed up with the Americans, and both civilians and soldiers alike viewed the Apache scouts as just as bad as Geronimo’s raiders.

“The Russian officer contemplated the fate of his young Apache prisoner. The village alcalde, with an eye toward the money the American soldiers brought into Sonora, pleaded for the Apache’s life. He feared that an execution would anger Capt. Crawford. Kosterlitzky relented, and Kid was fined $20 for disturbing the peace and sent back to Crawford’s camp, but he still grumbled over how he should have hanged the boy.

“‘These Indians are all the same to me,’ he forcefully declared. ‘Yaquis and Apaches—I have fought them all. They are all the same. In my country we knew how to deal with savages.’

“He looked us over with disdain as he spoke. ‘What was it the commander of your American army once said? The only good Indian is a dead Indian!’ He smiled: ‘Now that Gen. Sheridan would have made a fine officer in the Czar’s army.’”

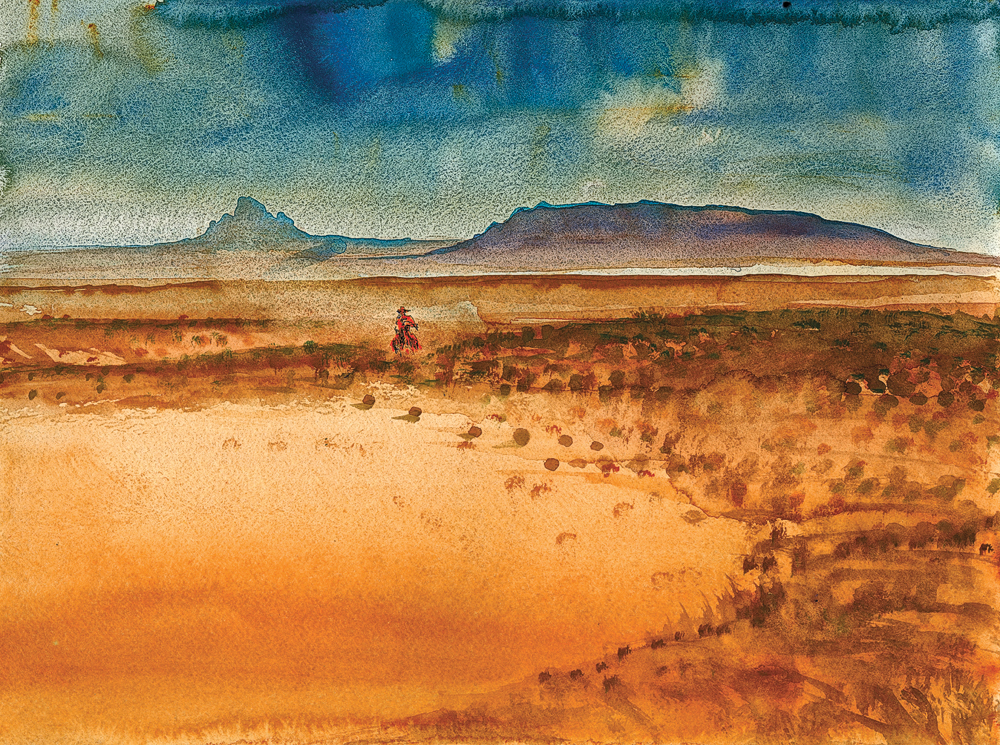

THE VILLAGE OF 300 WIDOWS

THE VILLAGE OF 300 WIDOWS

“We passed villages where the cemetery was larger than the town,” Young told the reporter. “Mickey told us we were now in the land of the killers, where men were easily insulted.

“Every morning, Mickey got up, and we were treated to our own personal rodeo. He mounted his mammoth jack, and the contest would begin.

“We knew at some point we were going to have to deal with the Mad Russian. Avoiding Kosterlitzky was a fool’s errand, because nothing went on in Sonora without that hard ridin’ Cossack knowing about it. He carried a sword with fancy script on the blade, which read, ‘When the owl sings the Indian dies.’

“The burning fires created their own weather, and we soon enough encountered some odd storms. A freak thunderstorm dropped a shaft of rain right on Mickey’s head and nowhere else. Horn and I were riding behind him, and, if I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it. Since he was so obsessed about clouds and cloud formations, I asked him what it meant. Mickey said, ‘Ussen wants me to be clean.’

“To the Apache, Ussen is the giver of life, like the Baptist’s Jehovah, only nicer.”

“‘That may be,’ quipped Horn, ‘Or, maybe Ussen thought you was stinkin’ up the prairie, and he needed to hose you off.’ That’s how those two teased each other, all the time.

“Mickey told us how an Apache shaman had cursed the Embudos site where Crook met Geronimo. On the day that the Chiricahua scouts were put on the train to Florida, a big earthquake ripped through Cochise County and flooded the mines in Tombstone, killing the town.

“I didn’t believe this until I looked it up, and it’s true.”

Epilogue

Tom Horn returned to Wyoming and, in 1903, was hanged for the murder of 14-year-old Will Nickell.

Doroteo Arango became known as Pancho Villa and went from being a bandit to a general in the Mexican Revolution.

Doroteo Arango became known as Pancho Villa and went from being a bandit to a general in the Mexican Revolution.

Hannah Hood Hill became the first of five wives of Miles Park Romney. Her great-grandson is former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney.

Hannah Hood Hill became the first of five wives of Miles Park Romney. Her great-grandson is former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney.

Emilio Kosterlitzky sought asylum in the U.S. after the fall of Mexico’s President Porfirio Díaz and found a job as an agent for the U.S. Justice Dept., working with J. Edgar Hoover. He died in Los Angeles in 1928.

Emilio Kosterlitzky sought asylum in the U.S. after the fall of Mexico’s President Porfirio Díaz and found a job as an agent for the U.S. Justice Dept., working with J. Edgar Hoover. He died in Los Angeles in 1928.

Mickey Free lived out his life on

Mickey Free lived out his life on

the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in northern Arizona. He died, in bed, in 1914.