Soon after forming the Pacific Fur Company, New Yorker Wilson Price Hunt developed a plan to begin fur trade exploitation in the Pacific Northwest.

Soon after forming the Pacific Fur Company, New Yorker Wilson Price Hunt developed a plan to begin fur trade exploitation in the Pacific Northwest.

He organized two ventures: one involved an ocean expedition of the Tonquin, which would sail around the tip of South America to Astoria, Oregon. The other, which he would lead, involved an overland expedition. With Donald Mackenzie, Hunt first traveled to Canada to hire French-Canadian voyageurs and trappers, including Ramsey Crooks, who signed on as a full partner. From there, Hunt made his way down a series of rivers to St. Louis before following the Missouri River to a wintering point on the Nodaway River, some 15 miles upstream from St. Joseph, Missouri.

Additional men joined the Hunt party there, including Robert McClellan, John Day, Joseph Miller, interpreter Pierre Dorian, Jr. with his wife Marie and two little boys, Jean Baptiste, age five, and Jean, age two, and two naturalists, John Bradbury and Thomas Nuttall, who would eventually become a curator of the botanical gardens at Harvard University.

John Hoback, Edward Robinson and Jacob Rezner, who had wintered with Andrew Henry of the Missouri Fur Company on Henry’s Fork of Snake River in Idaho, also joined Hunt’s party. Their presence changed the course of the trip because they were familiar with a route over Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains, Togwotee Pass. This region would become known as Jackson’s Hole. Although Hunt had intended to follow the route Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had taken in 1804-06, he opted for a more southerly route across Wyoming and south-central Idaho.

The overland party of 56 men, Marie Dorian and her two children, and 82 horses embarked from the Missouri headed toward Astoria in July 1811. Once across the mountains, they trailed through the Wind River Valley and took a route over the Wind Rivers that became known as Union Pass. From this pass, northwest of present-day Dubois, they spied the jagged mountain range Hunt called the Pilot Knobs. The French-Canadian trappers dubbed them Les Trois Tetons; we know them better as the Grand Tetons.

Overland Expedition Begins

I begin following Hunt’s route in Dubois, Wyoming, which is home to the Rustic Pines Saloon, Wind River Historical Museum and the National Bighorn Sheep Interpretive Center. My route heads north out of Dubois on U.S. 26/287 across Togwotee (pronounced toe-ga-tee) Pass and into Jackson Hole. I then travel southwest on U.S. 26/89/191 past the grandeur of the Grand Tetons to the town of Jackson—a great place to spend a couple of days hiking, fishing, floating or generally kicking up your heels in a cowboy saloon.

The Hunt party followed a portion of this route, and some members remained in the mountain valley that is now Jackson Hole (named in the 1820s for fur trapper David Jackson), but their primary route took them across the Wind Rivers south of Jackson on a trail traversed today over Union Pass (a good alternate route for adventuresome people with four-wheel-drive vehicles).

From Jackson, I pick up the Hunt party trail by traveling southwest on U.S. 26/89/189/191 to Hoback Junction. I then detour south through the Bondurant valley to the upper end of the Green River, north of Pinedale, Wyoming, where Hunt’s party spent time in camp, hunting on Horse Creek Meadows and preserving several thousand pounds of buffalo meat. Once back on their trail, I backtrack to follow the Hunt route crossing into Hoback Basin (named for John Hoback) and travel though the rugged Hoback Canyon toward the Snake River.

Fording the Snake River

At Astoria Springs (located off U.S. 189/191 south of Hoback Junction), the party began harvesting cottonwoods for canoes, and Hunt sent John Reed, John Day and Pierre Dorian down the Snake River in dugouts to determine if it was navigable. After a two-day reconnaissance, Reed returned and informed Hunt the route was impassable for canoes or horses, for which they gave the river a new name: Mad River.

Hunt followed the Snake River downstream. With Indian guides, he forded the Snake River, followed a well-traveled Indian trail along Fall Creek, crossed Teton Pass and dropped into Pierre’s Hole before traveling on to Fort Henry, on the North Fork of Snake River. Hunt noted: “We reached the fort of Mr. Andrew Henry. It has several small buildings that lie constructed in order to spend the past winter there. All stand along a tributary of the Columbia about 300 to 450 feet wide. We hoped to navigate it and we found some trees suitable for canoes.”

To remain on their general route, I backtrack to Jackson and then take Wyoming Highway 22 through Wilson and Victor, entering Idaho through Driggs and Pierre’s Hole.

From Fort Henry, the Hunt party resumed its journey, although the group was now smaller because some partners resigned, and others—including Edward Robinson, John Hoback and Jacob Rezner—remained in Jackson Hole.

Hunt noted in his journal: “We had cached our saddles in a spot that we showed the two young Snakes. They promised to take care not only of the saddles but also of our seventy-seven horses until one of us returned. The people of this area must suffer terribly from a lack of game … we left this place on October 19th.”

Using the Snake as a conduit, the Astorians floated downstream to the area west of present-day Milner, Idaho, where they were suddenly in a deep-walled gorge that became known as Caldron Linn (see the Road Trip article by R. G. Robertson, p. 66 June 2005). Here, one canoe capsized and French voyageur Antoine Clappine drowned.

Again, Hunt cached supplies before abandoning the increasingly turbulent river and preparing “to go in different directions in search of Indians.”

Main Party Splits

It was late fall by this time, and although Ramsey Crooks headed toward Fort Henry where the party had left its horses, he could not get there due to heavy snow. Subsequently, the main party split into two groups. Hunt followed the north bank of Snake River with 19 men and Marie Dorian and her two children. Crooks set out with other men along the south bank.

Driving across the Snake River Plain from Twin Falls to Weiser, Idaho, the journey today seems simple enough. I avoid Interstate 84 as long as possible, taking U.S. Highway 30 from Rupert to Bliss, where I have easy opportunity to detour to sites such as the Oregon Trail Ruts at Milner, the Stricker Store and Rock Creek Stage Station south of Hansen, the Salmon Falls near Twin Falls (which is now a developed picnic area; bring money to actually see the area of the falls up close) and the area of Thousand Springs, between Buhl and Hagerman.

On December 31, 1811, Marie Dorian gave birth to a third child; the following day, she was back in the saddle with the new babe in her arms and her two year old tied into a blanket carrier that was snug against her side. The infant lived only a week as Hunt and his party struggled through winter conditions and Hells Canyon of the Snake River, eventually washing up on the shore near a Nez Perce village where they obtained aid.

For my part, I follow Hunt’s route on land, taking Highway 95 through Weiser to Lewiston, Idaho. There are access points to Hells Canyon (for information contact Hells Canyon National Recreation Area). At Lewiston, I get on the river itself (something I dislike intensely), riding a jet boat upstream to Hells Canyon and being eternally grateful that the captain of the boat gets me safely back to Hell’s Gate State Park and dry land without a soaking as some of Hunt’s party had endured.

Destination: Astoria

Back in the car, I continue west on Highway 12 to Walla Walla, Washington, site of Fort Walla Walla and the Whitman Mission. From this point west, most of the Astorians had a rather uneventful journey down the Columbia to its mouth and Astoria. Highways in Oregon (Interstate 84 and U.S. 30 west of Portland) and Washington (Route 14, Interstate 5 north and west on Washington Route 4 to Route 401, then across the high bridge over the Columbia to Astoria) provide a land route, but the Columbia is a river of commerce and it is possible to cruise the watercourse as Hunt and his Astorians did.

Some members of Hunt’s Party beat him to Astoria, arriving there on January 18, 1812. Hunt didn’t make it to Fort Astoria until February 15 of that year, when he wrote in his journal: “We had covered 2,073 miles since leaving the village of the Arikara. July 18th to February 15th—7 months.”

Meanwhile, Ramsey Crooks and John Day, separated from the others, wandered west, becoming almost hopelessly lost while following the Umatilla River and then the Columbia for weeks. A fur trading party of Astorians on their way back to Fort Astoria found them on the Columbia in early May 1812, nearly naked, starving and teetering on the edge of insanity. They finally made it to Fort Astoria on May 11.

Frequent True West contributor, Candy Moulton is the author of Chief Joseph: Guardian of the People, part of the American Heroes series from Forge Books.

Photo Gallery

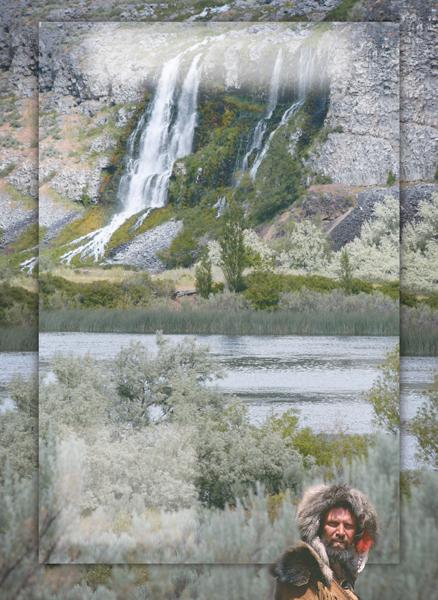

– Courtesy Wyoming Tourism –

– By Karen A. Robertson –

– By Candy Moulton; Inset courtesy Wyoming Tourism –