When his hired hand stomped off in a huff that chilled November day in 1895, foreman Jim Potts knew it would be up to him to take care of his band of sheep.

When his hired hand stomped off in a huff that chilled November day in 1895, foreman Jim Potts knew it would be up to him to take care of his band of sheep.

Potts headed to their grazing spot near the North Fork of the Powder River, just north of Kaycee, Wyoming. He watched his “woolies” work their way south across the range that had been recently brushed with a thin sheet of new snow, before he trudged toward three large sandstone buttes. From there, he thought he could best keep an eye on his flock.

As he made his way to the north side of the buttes, he found a large piece of caprock had split off. He spotted a space—about eight or 10 inches deep—that someone had neatly filled with small stones. As he plucked out the pebbles, he saw what looked like a rectangular piece of bright metal. At first, he thought it to be a gold brick, rumored to have been stolen in Nevada some months before, and then cached here in Johnson County. But as Potts dug deeper, he instead found a five-pound Prices Baking Powder can with a loose lid.

As he removed the tin, a bright-skinned, nearly new, nickle-plated, .45 caliber Colt revolver fell out. It had a lanyard swivel on the butt of its pearl-handled grip. From inside the tin, Potts pulled out a fistful of papers that had been shredded by varmints. Disappointed that he hadn’t found gold, Potts pocketed the handgun and went back to watching his sheep. He had no idea his discovery would one day help solve a notorious murder.

Four Decades Later

The revolver stayed in a bureau drawer at Potts’ home for the next four decades, with few people, other than the family, knowing of its existence. Then in 1938, “Black Billy” Hill, a small-time rancher of questionable character, returned from Canada to visit. Johnson County Sheriff Martin A. “Mart” Tisdale took Hill, his deceased father’s one-time friend, to visit his old ranch site.

According to the sheriff, Hill pointed to three isolated sandstone buttes that rose sharply from the plains and dropped a bombshell. It was there, Hill claimed, that notorious Red Sash Gang member Ed Starr said he had buried a gun and papers he took from U.S. Deputy Marshal George A. Wellman—after he had killed him.

When the lawman returned later that day to the Johnson County Courthouse in Buffalo, Wyoming, he told Hill’s tale about the cached gun to an astonished Warren Lott. Lott’s boss was County Treasurer J.W. “Joe” Potts, whose father was Jim Potts. Upon hearing the story, Joe told how and where his father had found a Colt revolver 43 years earlier.

When ex-Buffalo Mayor C.H. Burritt learned of the story, he had Thomas “Tommy” F. Carr, a one-time mail carrier in the area, and famed lawman Joe LeFors examine the weapon. Both confirmed that the gun had belonged to Marshal Wellman and that they had seen the sidearm many times on his hip. Burritt also asked Lora “Lorry” H. Reed—a billiard parlor operator—if he recognized the pistol. “That’s it!” exclaimed Reed, who just before the murder had been one of Wellman’s ranch hands. Reed assured the mayor that he not only remembered the gun, but even recalled a “circle on the left side” of its grip, which Burritt confirmed to be true. Not having a gun of his own at the time, Reed remembered that his admiration of the revolver was so great, “every chance he got, he would examine and fondle” it.

More than four decades after the pistol had been found by chance in the tin—Hill’s casual aside would help solve one of the most mysterious murders in Old West history.

Ambushed

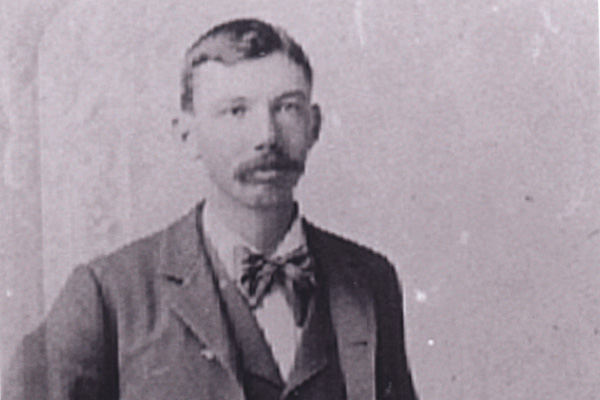

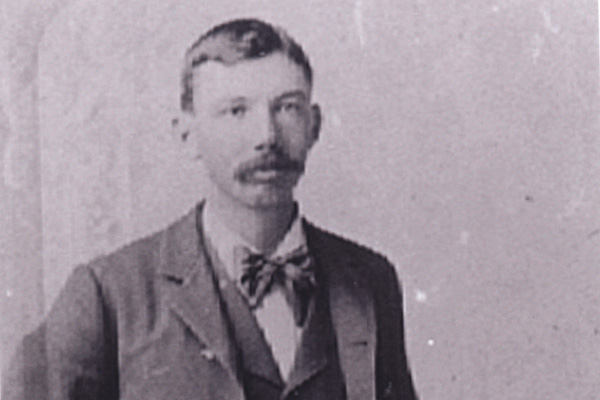

George A. Wellman, a Canadian by birth, had hired on at the HOE Ranch and became its foreman in 1887. From that vantage point, he watched the growing bloodshed between ranchers and rustlers that became the Johnson County range war.

Wellman apparently bought his beloved Colt around July 20, 1889, after “Cattle Kate” Watson and her lover Jim Averell were hanged near Independence Rock, Wyoming, on suspicion of brand-running.

Their deaths began a series of murders and attempted murders among cow thieves and ranchers. On June 4, 1891, a group of thugs—presumably backed by ranchers—posed as lawmen and took Tom Waggoner, a reputed horse thief, from his home. Folks soon found Waggoner decorating a cottonwood branch near Newcastle, Wyoming. Five months later, on the Powder River, Nate Champion, another suspected cow thief, was almost murdered. That same month, assassins hid beneath a bridge some 15 miles south of Buffalo, and as 23-year-old Orley E. “Ranger” Jones rode by, they shot him to death. Soon thereafter, some seven miles north of where Jones had died, assassins left rancher John A. Tisdale stone-dead. Friends found the corpse of Mart Tisdale’s dad in a pile of Christmas toys and supplies the old man had planned to take home to his family. By April 10, 1892, such depredations by both sides finally exploded into a full-scale war that raged for three days.

“[Johnson County is] a good place for fugitives from justice,” Wellman once said. “There are more desperate criminals there than probably could be found in any place on earth. These men lead a riotous life. They are notorious gamblers, thieves and murderers, and none of them ever think of working for a living. The rough country enables them to carry on their depredations with a free hand. They steal unbranded and stray cattle—branded cattle, too, sometimes—and in that way they have been getting rich at the expense of the cattle owners. There has always been trouble between the two parties.”

The cattlemen had tried time and time again to have these outlaws punished, but no matter how strong the evidence against them, it was impossible to secure conviction as the juries almost always decided against the cattlemen. The ranchers finally resolved to take the law into their own hands.

Accordingly, it’s understandable why soon after Wellman went back East to wed Lucy C. Clark on April 21, he insured his life. It seems he also planned to quit the West, as he left his wife behind and told his family he intended to close up his affairs and move to Bay City, Michigan.

Soon after his return to Wyoming, Wellman teamed up with rancher Robert Lee Gibson, and they secretly swore oaths as U.S. deputy marshals to help stop the lawlessness. Presumably, Wellman’s instructions were to “assemble evidence to prove that the homes, ranches and herds of the stockmen were being looted and rustled.” That evidence would be sent to Washington D.C. and, it was hoped, would persuade President Benjamin Harrison to declare martial law in Johnson County.

The orders Wellman received were simple and to the point, and they may have worked, had he and Gibson not discussed them in a crowded bar.

Armed with his secret assignment, Wellman returned to his ranch, paid his wranglers and fired several suspected thieves, including Austin Reed and his 19-year-old brother, Lorry.

On the night of May 8, Wellman prepared for his trip back to Buffalo, taking along his prized pistol. He left the next morning with Thomas J. “Big Mouth” Hathaway, a 36-year-old ranch employee.

The two were approaching Nine Mile Divide when they heard shots. Hathaway later reported: “Well, I and Mr. Wellman was riding side by side . . . talking and the first thing I knew I heard a couple of shots just very quick right together like; made my horse jump so did Mr. Wellmans . . . and as I pulled up my horse I faced him [Wellman] and he threw up one hand and hollo’d; he did not hollo as though he was hurt, he holo’d like he was trying to hale somebody or simply as a man would hollo ‘hey’ at somebody and at that time there was two more shots fired right after that so close that I could not tell, and I started my horse on the run and got away from there. . . .”

Hathaway said he did not return to Wellman’s body, because he “was entirely unarmed.”

What Hathaway did not know is that soon after Wellman hit the ground, someone stole the lawman’s pistol from his still warm body and rushed it from the scene.

Red Sash Boys

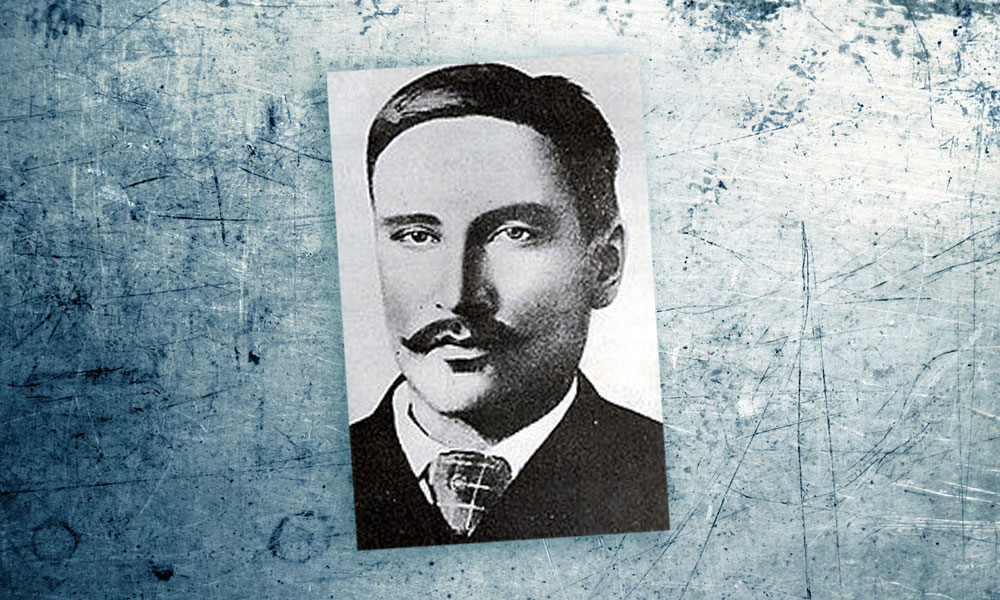

It would take years for anyone to piece together what had happened. A decade after the killing, Mayor Burritt told of a ride he had with fellow herder Austin Reed, around 1892. Reed admitted he was present when members of the Red Sash Gang drew lots to determine who would kill Wellman. “It had been framed for Ed Starr to draw that ticket,” Reed noted. “Starr was a killer and would as soon shoot a man as a coyote.” In fact, Reed said that he “had often heard Starr imitate Wellman’s cry when he saw he was going to be killed.”

But perhaps the most damning evidence came from the mail carrier Tommy Carr, who said he had stayed at a ranch with the killers the night before they ambushed Wellman. The morning of the murder, he saw three men steal out of camp: “Black Henry” Smith, Ed Starr and Charles Dembrey.

Sworn testimony from the coroner’s inquest after Wellman’s murder helps paint a clear picture of what happened next. The tracks of the three men showed that one of them stayed out of sight with the horses, while the other two hiked to the ambush site. Cigarette butts wrapped in yellow corn-leaves, which were found at the site, verified the men had waited for Wellman.

One gunman crouched behind some sagebrush, while the other hid in a gulch about 65 feet from the left side of the rut road. When Wellman and Hathaway came in sight, they were caught in a crossfire. It took but one .44 caliber Winchester rifle shot—apparently from the man on the hill—to do the job. Wellman died quickly as the slug severed his spinal cord, ripped through his vital organs and lodged beneath the skin of his chest.

After the gang members made sure of their kill and removed the Colt from Wellman’s holster, they fled, knowing full well they could never show off their loot.

So they buried it. And it may have stayed hidden forever, if not for Potts’ discovery of the baking powder tin.