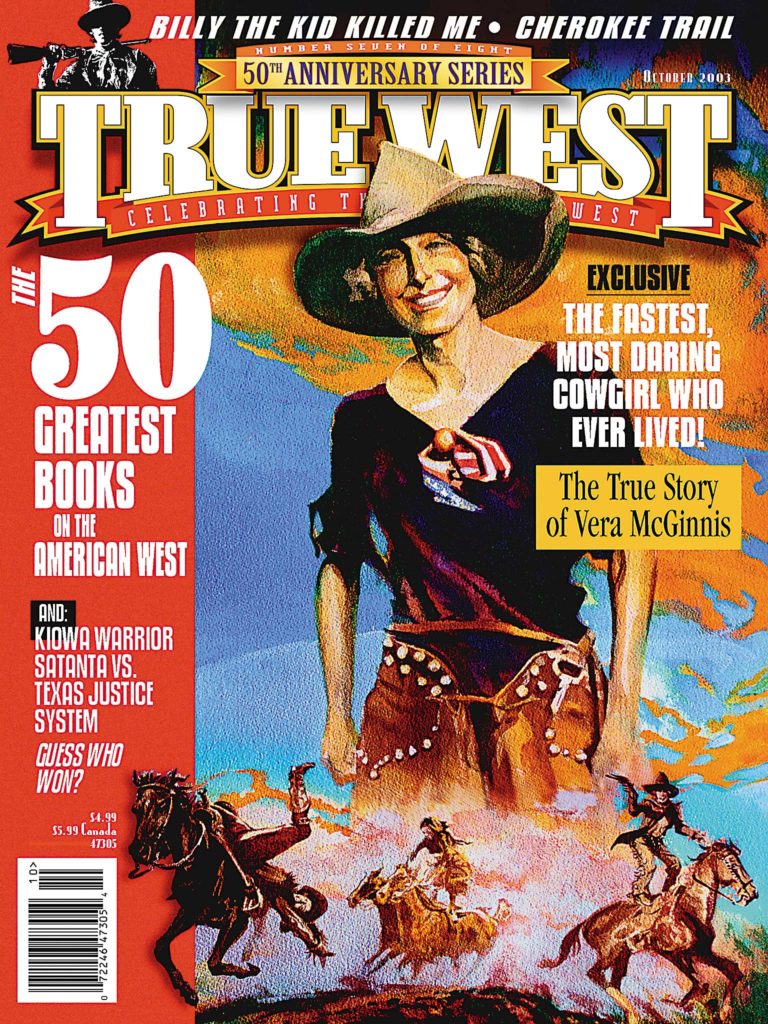

She hardly even tried to describe the pain, but of course, how could she? What words are there to recount a ton of horseflesh landing on your tiny body, doing colossal damage: breaking your back in five places, busting three ribs, destroying a hip, shattering a collarbone, puncturing a lung.

She hardly even tried to describe the pain, but of course, how could she? What words are there to recount a ton of horseflesh landing on your tiny body, doing colossal damage: breaking your back in five places, busting three ribs, destroying a hip, shattering a collarbone, puncturing a lung.

On her way to becoming America’s premier woman rodeo champion, Vera McGinnis had been thrown before, stepped on before and dragged before, but even injuries permanent enough to require changes in her trick-riding act were nothing like this.

Years later when she wrote her autobiography, Vera devoted just a couple of pages to that day in 1934 when her trick pony Rosie somersaulted on top of her during a relay race. Nor does she dwell on the callous treatment she got in two hospitals—one pawning her off on the other, neither giving any medical care because she was poor, had no insurance and surely was dying anyway.

You can’t blame her. How could she bear to remember people who cared so little about a broken human being? But she does write how surprised she was when a doctor told her she probably wouldn’t make it.

“I won’t die,” she told him.

Then you’ll end up a cripple, he said.

“No, I won’t be that either.”

She didn’t die and didn’t end up a cripple, but you have to imagine, at that moment, 42-year-old Vera McGinnis knew her days in the rodeo ring were over.

It had been a 21-year ride and she’d forever have the gorgeous trophies won around the world and the mountain of newspaper clippings attesting to a prowess in the ring that made her “the girl to beat.” But the year that should have been the pinnacle of her career, turned out to be the end.

There’s certainly no way to relate what that kind of hurt feels like. And so Vera McGinnis, one of America’s pioneer cowgirls, kept it to herself.

IT HAD TO BE in her genes, or else how did Vera McGinnis do so many remarkable things:

• Jumped an irrigation canal on a “four-legged, crop-eared babysitting burro” named Croppie in 1895 when she was just three years old—a moment she recalled as “rodeo germ’s first nudge.”

• Won the very first riding competition she ever entered at age 13, taking home a gold-handled umbrella “which I needed like four legs.”

• Learned to trick ride in just eight days in 1913 with such skill, on her first time out, she tied reigning trick-riding queen Tillie Baldwin.

• Ran the clock her first time on a bronc and her first time on a raging bull.

• Invented the “flying change”—getting from one horse to another without touching the ground—and was one of the few, man or woman, to circle a horse’s belly at full gallop.

• Was the nation’s only “girl jockey,” competing and often winning in the “Sport of Kings” against the men.

• Won titles, trophies and prize money on three continents, appearing in more countries than any other cowgirl and earning the reputation as the girl who “rode the fastest and dared the most.”

• Singlehandedly changed the fashion of the rodeo ring, as she was the first woman performer who dared to wear pants.

• Appeared as a Hollywood stunt double and was given a short film series until it became apparent her talent didn’t match her beauty. (In The Cimarron Land Rush, she doubles for Estelle Taylor and is the only woman in the runaway scene, since all the others are men in wigs and dresses.)

• Published her autobiography, Rodeo Road: My Life as a Pioneer Cowgirl in 1974, which was hailed as “one of the most authentic books ever published about the sport—a must read for anyone interested in rodeo history.”

• Inducted into the Cowgirl Hall of Fame in 1979 (and to this day, she’s one of their favorite icons), and inducted into the Rodeo Hall of Fame in 1985.

Vera McGinnis began this incredible journey at a time when women didn’t even wear pants around the house; when they wouldn’t be seen in public without their corset; when they didn’t have the right to vote and couldn’t serve on juries. It was a time when professional opportunities for women were greatly limited: the few working outside the home made barely half as much as men. It was a time of strict codes and taboos, when women who displayed “masculine tastes”—like competing in men’s sports —were considered “sexual inverts.”

And yet, Vera and her fellow buckaroos overcame all those restrictions and stereotypes to make their way in the rough and wild world of rodeos. As she began her career, over 200 women earned a living in rodeos or Wild West shows—about the best paying job open to women. Stars such as Mabel Strickland, Kitty Canutt, Prairie Rose Henderson, Fox Hastings, Tad Lucas, Ruth Roach and Florence Hughes Randolph left their mark forever.

Vera McGinnis and these rodeo pioneers were America’s first professional women athletes.

YES, IT HAD TO BE IN the genes and it was. But not from her father as you’d expect—him being a dentist who encouraged his daughter’s independence but preferred small towns to a ranch. No, the natural talent came from her mother Sarah, the real “ramrod” of the family and one of New Mexico’s pioneer ranch women.

Vera’s earliest memories were of the ranch her mother finally convinced her father to buy—a “cow outfit down on the Cimarron” near Clayton, New Mexico. The family moved to the ranch when Vera was three, but stayed only a few years, as the ranch never supported the family. By the time she was 10, the family had settled in a little town in Missouri.

So Vera wasn’t raised as a ranch girl, like most who took to the rodeo circuit; she didn’t even talk like a Western woman. Sure, she had an inkling for four-legged animals, but it was a two-legged, handsome cowboy who got her into the ring.

Her “undoing,” as she’d later joke, came in the summer of 1913. Art Acord, a “big blond Don Juan” she’d met along the way, showed up in Salt Lake City for the 4th of July’s Frontier Day Celebration. Vera had recently moved to town to make her living as a stenographer. She passed for 18, but really was 21, and was pretty as a picture. (Today’s popular actress Kristin Scott Thomas is her dead ringer look-alike.) Acord invited Vera out to the rodeo and gave her the lasting nickname of “Mac.” She hung around to be near him, but Acord turned out to be a matchmaker, rather than a lover, and introduced her to the man who would steal, hold and then break her heart.

Rodeo competitor Earl Simpson had sparkling black eyes, straight black hair, a cleft chin and was “a bit more reserved without a horse under him.” Vera was instantly hooked.

Toward the end of the rodeo run, she overheard a promoter wishing he had another girl relay rider and she instantly volunteered. She took third. The next day she quit her job, packed her few belongings and joined the rodeo circuit.

“That was the decision that shifted the indicator on my life’s chart,” she’d write. “If I’d pulled up right then, I likely would have missed the years of hardship, heartache, fun, adventure, a smidgen of fame, and, finally, a broken body. But I’m glad I didn’t, for I can honestly say the glamour never faded. It dimmed once in a while when I was hurt or overworked, but after a rest I always felt that I wouldn’t trade being a rodeo cowgirl for any other profession.”

SHE MARRIED EARL in 1914, but it would last only 10, often miserable, years. Although she claimed he was her first husband, True West discovered she had been married once before as a teenager, but that marriage lasted only a few months. In 1931, she would marry an “easy-going, big six-footer” named Homer Parra, who she stayed with until her death.

And who can decipher the real story of Vera’s long relationship with the Sultan of Johore, one of the world’s richest men? She met him on tour in Indonesia and they communicated for decades afterwards—he sometimes signed his handwritten letters “please accept my little love to you.” He shot tigers and panthers for her and sent the skins to her home in California. He also sent dozens of pictures of himself and was forever begging her for new snapshots. If she felt a “little love” for the man, she kept it to herself, although her scrapbook includes a clipping on his death in 1959.

No, love wasn’t Vera’s strong suit.

But give her a horse and she could do magic.

YOU’VE GOT TO REEK confidence to call yourself “The Greatest Show on Earth,” but then nobody ever accused the Ringling Brothers of lacking moxie. When the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus opened in New York’s Madison Square Garden in March of 1923, it brought with it the reigning stars of the rodeo world and by now, Vera was one of them.

If the rodeo ring was dust and dirt, Madison Square Garden was spic and span. It all seemed so glamorous, especially the spectacular opening, when everyone rode through the ring in beautiful, if improbable, costumes.

“We rode black horses with gigantic hoopskirts hanging from our waists, the flounces reaching the ground,” she remembered. Add to that the picture hats and ostrich plumbs and you can see why she thought they “looked like mammoth Dresden dolls.”

After the Garden, she joined the circus on its nationwide tour, but soon jumped at the chance of giving Europe its first taste of a true rodeo.

In 1924, Europe was a hoot for Vera McGinnis. She and nearly 200 of America’s other top rodeo hands went over on an old troop ship with promoter Tex Austin for the “World Championship” at Wembley, England.

“Without doubt, we were a thrilling sight to those Londoners who had never been any closer to our great West and its inhabitants than the motion-picture screen,” she’d later write.

Vera got a humorous reminder she was on foreign soil when her landlady asked her “what time do you wish to be knocked up in the morning, Miss McGinnis?” Trying to keep a straight face, Vera said she’d like her wake-up call at 7 a.m.

For the first performance, 93,000 people showed up and the rodeo stars became the toasts of London. Lavish dinners were thrown for them by the Prince of Wales, who hadn’t yet met the woman he would abandon the throne to marry (and decades later, Vera’s look-alike, Kristin Scott Thomas, would portray Wallis Simpson in the movies). London hostesses vied for the cowgirls and cowboys, requesting that they wear their Western clothes to the fancy parties.

The Wembley Rodeo was a 16-day show, with 32 performances. Vera rode one bucking horse a day, did a trick riding demonstration for the afternoon and evening shows and rode a daily relay race. She won two world championships, the trick riding contest and the cowgirl’s relay race. The rodeo was such a success, management decided to add another week. After that, another promoter booked Vera and other champions for a month at the London Coliseum, then the largest stage in the world. She later went to Dublin for that country’s first rodeo. Vera would always keep a soft spot in her heart for Ireland, where she was treated like a movie star. When an injury demanded she spend a few days in bed, her room filled up with flowers from adoring fans.

She also won the trophy that would forever be her favorite. It was made of elephant tusk with walrus-tusk handles. (Later, when she retired, she made it into a lamp and read by it in her favorite chair. The trophy has now been “delamped” and is on display at the Cowgirl Hall of Fame.)

BY 1934, VERA McGINNIS had seen the world, won about every rodeo championship, made enough to support herself—mostly just enough to get by—and was in excellent health for the first time in years. All the injuries she had suffered along the way were healed, and she was riding in fine form.

Then came the relay race in Livermore, California, on June 10, 1934. “My big wreck,” Vera would call it.

Reba Perry Blakely later wrote that she was riding beside Vera that Sunday.

“Vera started whipping her relay mount and it fell—right in front of me but down on the rail, inside, and did a heels over head complete summersault, crushing Vera and her body into a railroad tie fence post. Horrible sound; a horrible sight for me to witness. Vera never again regained that wonderful, vivacious personality all we pioneers of rodeo knew.”

“One minute I was a champion horsewoman, riding as well as I’d ever ridden in my life, the next, a crumpled heap,” Vera said in her autobiography.

But what happened next was even worse.

“I was taken to a hospital in Livermore and X-rayed that afternoon. A nurse was kept busy removing the pan full of clotted blood that kept rolling out of my mouth. I couldn’t speak; I couldn’t even turn my head. . . . After visiting hours my doctor asked me about money. I made him understand there was no insurance or bank account for him to draw on, and the next thing I was aware of was being slid into an old rattletrap of an ambulance. This was seven hours later and still nothing had been done for me. Perhaps it was the money.”

She was sent off to the Alameda County Hospital without anyone notifying her husband or the rodeo association, and without a shred of paperwork to explain who she was or what had happened. An angry attendant kept after her, and she finally struggled to explain she lived near Los Angeles. “No one wanted to touch me because I didn’t live in Alameda County. Who had dumped me on them? It sounded as though they expected me to get up off that stretcher and leave!

“But dumped I had been and there I stayed until five o’clock the next afternoon without a single thing being done for me. Several times during that interval men in white came to my cot, lifted my right leg and rotated it in mid-air. I could hear the bones grind in my broken hip, and so could they, for they’d listen. I’d scream, of course, and the nurse would tell me to shut up. Then they’d lay the leg back down, not too gently and walk on. Once a different intern came on duty and when he read my chart he said, ‘Is she still here’? It didn’t occur to me that he thought I’d be dead by then.”

Monday afternoon her husband finally found her and rushed her to Oakland Hospital, where she was told her chances of survival were slight. Five weeks later, she walked out of the hospital with the help of a cane.

A year later, Vera wrote to a friend in England, “I went to my first rodeo last Sunday at the Hoot Gibson ranch. Last year I won everything up there and this year I went as a Has Been. It has been a little hard to take but I have decided to sell my saddles and all my equipment. I walk with a limp which I think I will overcome in time but I am going to try and get interested in something else.”

Her new interest was writing her life story, which took her decades. The book was published in 1974 to glowing reviews, but poor sales. It is now out of print.

She and Homer settled into a quiet life in California. They raised thoroughbreds. Homer was a wrangler for the movies; Vera was devoted to her pets and her garden.

She had two last moments of fame as reporters again came calling to tell the story of a rodeo pioneer: in 1979, when she was inducted into the Cowgirl Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas, and then in 1985, when she was inducted into the Rodeo Hall of Fame in the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

“Many other aspiring cowgirls lacked her gritty resolve, and more than half the women who participated in professional rodeo during this era dropped out after only one or two years on the circuit,” notes author Mary Lou LeCompte in her book, Cowgirls of the Rodeo.

Eventually, Vera and Homer’s health deteriorated so much, they were put in a nursing home in Northern California. Vera was confined to a wheelchair and outlived Homer. “Vera is very unhappy and is pretty much a problem as she has been so independent all her life,” a friend noted.

Vera McGinnis Farra died on October 23, 1990. “She hadn’t been in any pain,” the friend reported. She was 98 years old.

“I would do it all over again,” Vera said in one of her last interviews, “if they could leave out that last fall.”

Follow the joys and sorrows of this pioneer cowgirl in upcoming “Chapters of Vera’s Life.” In the next issue of True West, find out how Vera changed rodeo fashion.