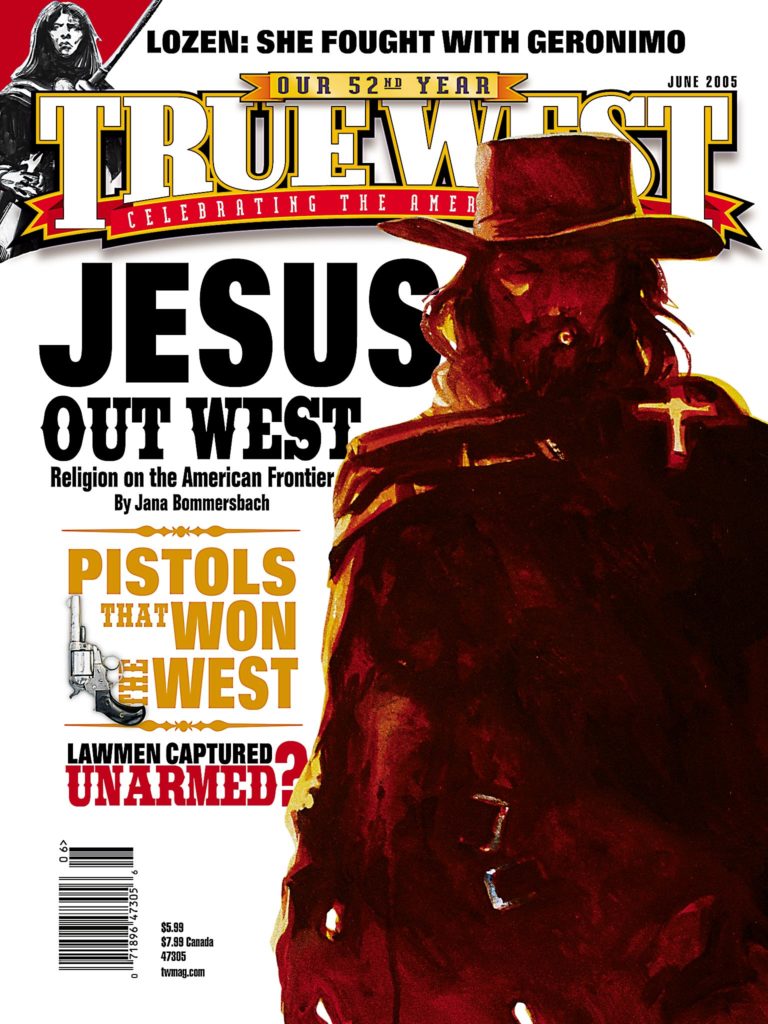

“The stories of Geronimo, Crazy Horse, and Custer pale beside the tale of another warrior—one who fought relentlessly, successfully and against all odds almost continuously for forty years…. But you’ve probably never heard of her.”

“The stories of Geronimo, Crazy Horse, and Custer pale beside the tale of another warrior—one who fought relentlessly, successfully and against all odds almost continuously for forty years…. But you’ve probably never heard of her.”

That’s how Arizona author and historian Peter Aleshire introduces us to Lozen, the Apache shaman who has been almost entirely overlooked by history. Yet, she was honored, respected and admired by her fellow Apaches. Some called her the Apache Joan of Arc; many saw her as “the shield of her people.”

From the time she came of age in the 1840s until she was exiled with Geronimo to a Florida swamp in 1886, Lozen played a crucial role in the Apache conflict to keep the land their god had given them—first with the Mexicans and then with the Americans who laid claim to the same real estate.

“Lozen is my right hand,” Chief Victorio bragged about his younger sister, who one historian has called “America’s greatest guerrilla fighter.”

The Discovery Channel notes, “Lozen was a multi-talented woman: not only was she a prophet and a skillful warrior, but a healer and midwife, too.”

Most of all, Lozen was gifted with a special talent that her people believed was divinely inspired.

A warrior from the start, Lozen was born into the Warm Springs or Chihenne Apache band in the early 1830s. This band saw Ojo Caliente—between what’s now Silver City and Socorro in New Mexico—as their spiritual home.

Like most Chihenne children, Lozen was trained early in the skills of survival. Girls, as well as boys, learned to fight, hunt and ride. Her skills earned her a name that translates into “Dexterous Horse Thief.”

Lozen’s most special talent was her clairvoyance in identifying danger. It’s said she employed a special ceremony to detect the enemy. Standing with her arms outstretched, she’d slowly turn, singing a song until she could “feel” the direction of the enemy—her palms turning hot and a deep red color. It is said she was always right, and her “ceremony” was sought often.

When she was a young woman, when the Apaches still controlled their sacred lands, Lozen’s band was led by Mangas Coloradas, the father-in-law of Cochise. He knew the Apaches could not win the fight over the land with the White Eyes and urged his people to make peace. He was so determined, that under a flag of truce, he went alone to talk with the soldiers.

Instead of talking peace, on January 18, 1863, the soldiers tortured Mangas Coloradas, shot him, cut off his head, boiled it and sent it to Washington, D.C. (Geronimo later called this the greatest wrong ever done to the Apache.)

And it set the stage for years and years of bloodshed.

Lozen was there for all of it. Like the warriors, she always resisted the imposition of reservation life, which replaced their hunting and crops with rations of “stringy beef and moldy flour.” The U.S. Government repeatedly refused her people’s request to remain on their sacred land, forcing them onto the San Carlos and Mescalero Reservations. Instead of complying, Lozen joined the warriors who fled into Mexico.

Years later, Apache warrior Kaywaykla told historian Eve Ball about Lozen: “I know of no other woman bidden to the council, but that was because no other had the skills as a warrior that Lozen did. She could ride, shoot and fight like a man; and I think she had more ability in planning and military strategy than did Victorio.”

Victorio and Lozen eventually tried living on the San Carlos Reservation, but it was impossible. Their people were dying of disease, starvation, idleness and whiskey. So in 1877, he and Lozen led 300 warriors, women and children back to Ojo Caliente, the land their creator had promised them “as long as the mountains stand and the rivers flow.” For almost two years, they lived there, until word came that soldiers were on the way to force them to move. It was the last straw.

So many lives and so much misery would have been avoided if the Whites had just left them alone in their homeland. The result is what we know as the brutal, bloody Apache wars.

The next year was one of constant flight, and when ammunition ran low, Victorio sent Lozen back to the reservation for more supplies. She took along a pregnant woman who gave birth along the way, making the long trip even longer. Lozen was devastated when she learned that in the meantime—when her ceremony was needed the most—Victorio had been killed in an ambush in Mexico.

Lozen joined a band led by the warrior Nana that spent the next two months in retaliatory raids. “Its sole goal was to kill as many settlers as possible,” reports Wynne Brown in More than Petticoats: Remarkable Arizona Women. “They covered 3,000 miles in two months, killed hundreds, won seven battles, stole 200 head of stock, and thanks to Lozen’s skill in locating the enemy, never lost a warrior.”

Lozen eventually joined the band led by Geronimo, the most feared and loathed Indian in America. He vexed, angered and terrified settlers and soldiers for so long that at one point, a full one-fourth of the entire U.S. Army was deployed to capture him.

In March 1886, Gen. George Crook—the Grey Fox—held a historic meeting with Geronimo to negotiate his surrender.

Aleshire notes that Lozen attended the meeting, staying in the background. “The leaders hid her importance when talking to the White Eyes, partly to protect her and partly so she could continue to be their messenger and go into the soldiers’ camps, counting their guns,” he writes. “So Lozen did not speak and Grey Fox did not bother with her because the White Eyes did not think women important.”

Geronimo agreed to surrender under the promise he and his people would be imprisoned with their families for no more than two years and then returned to the San Carlos Reservation. But within hours, he changed his mind and fled. “With him went the last of the free Chihenne: Lozen, nineteen warriors, fourteen women and six children,” Brown notes. “They rode hard, rarely slept, relied heavily on Lozen’s ceremony, and raided from Mexico north to Tucson and back.”

Aleshire notes Geronimo’s flight was a “bombshell,” as the public had grown “almost hysterical as a result of continued raids.” From Washington came a new, harder line: only the unconditional surrender of the renegades was acceptable.

General Crook was replaced by Gen. Nelson Miles, who used Geronimo’s old friends to help track him down in the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico.

On September 8, 1886, in Arizona’s Skeleton Canyon, Gen. Miles made a “treaty” with Geronimo.

The warrior placed a stone on a blanket between the men and swore to end the bloodshed. “Our treaty is made by this stone,” Geronimo said, “and it will last until the stone should crumble to dust.” Lozen stood by, watching it all.

Historians suggest it was weariness, homesickness for their families and the understanding that the soldiers would never relent in hunting them down that led Geronimo to finally trust the word of the White Eyes.

The band rode with Miles to Fort Bowie, where Aleshire notes the general again promised: “You will have a separate reservation with your tribe, with horses and wagons, and no one will harm you.”

But once he had Geronimo in his hands, Gen. Miles brought all the Apache who’d been living peacefully on the San Carlos Reservation to the fort. “He put them all in corrals, took away their weapons and made them prisoners,” Aleshire reports. Then the soldiers marched 381 people, including 103 children, to railroad cars that took them to prisoner of war camps in Florida.

Lozen’s name then disappears from the historical record. It does not appear on the train’s roster, but historians believe she was held first at Fort Marion in Florida and then at Mt. Vernon Barracks in Alabama.

These imprisonments were devastating to the Apaches. One fourth of the prisoners died within the first four years, often of malaria or tuberculosis. Historians believe one of those casualties was Lozen.

Brown notes she died in Alabama of the “coughing sickness” on June 17, 1889.

Aleshire adds this final note to the remarkable life of the warrior woman: “So the woman Victorio describes as ‘the shield of her people’ died in a strange place surrounded by her enemies, where not even the coyote’s call could be heard.”