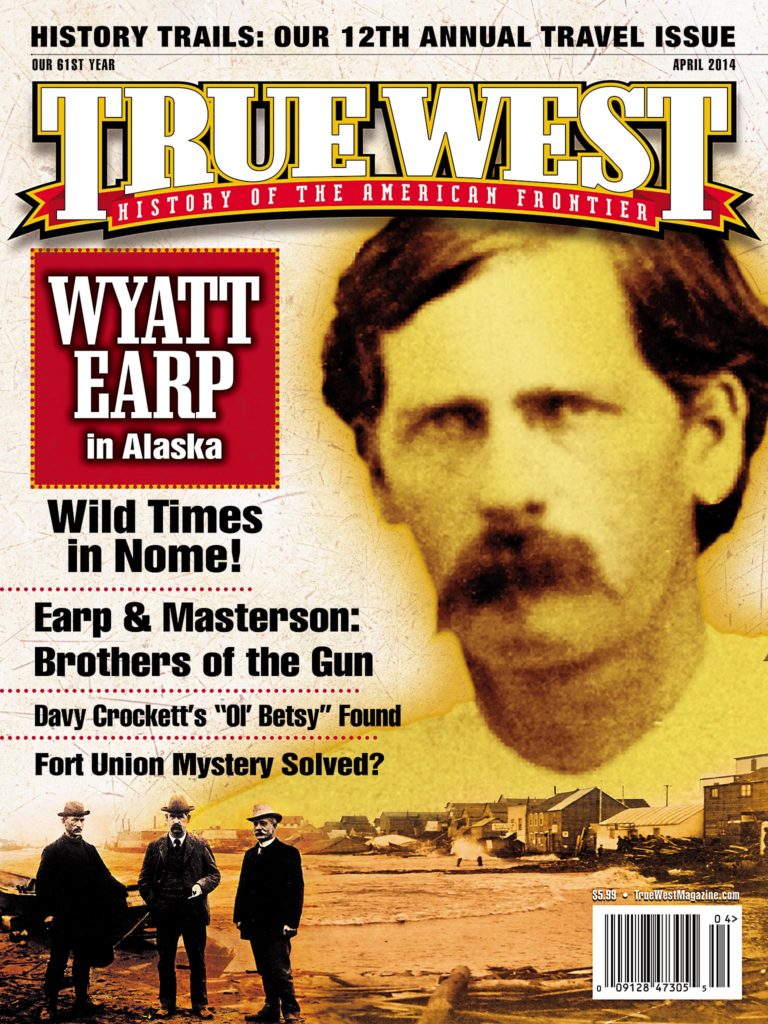

In the summer of 1899, the sleepy fishing village of Nome, close to the Arctic Circle, remote even by Alaskan standards, became one of the most exciting places in the world. Gold had been discovered on the shores of the Bering Sea the previous summer. Josephine and Wyatt Earp were drawn to Nome as one more place to seek their fortune.

In the summer of 1899, the sleepy fishing village of Nome, close to the Arctic Circle, remote even by Alaskan standards, became one of the most exciting places in the world. Gold had been discovered on the shores of the Bering Sea the previous summer. Josephine and Wyatt Earp were drawn to Nome as one more place to seek their fortune.

Their journeys had taken them from Arizona to Utah, Idaho, Colorado, Texas and California. After their investments in downtown San Diego soured and Wyatt’s reputation took a beating in a prizefighting scandal in San Francisco, the couple retreated to the Arizona desert just before news of the Klondike goldfields hit.

Their first trip to Alaska was delayed when Wyatt injured his hip in an accident in San Francisco and Josephine suffered a miscarriage. In 1898, they got as far as Rampart before the Yukon River froze them in place for the winter. Rampart was a friendly place, but far from the real action. They left with the spring thaw and headed for St. Michael, where Wyatt sold beer and cigars for the Alaska Commercial Company. But a barrage of letters from their friend Tex Rickard, deriding Wyatt’s steady income in St. Michael as “chickenfeed,” convinced them to head for Nome in 1899.

Since Nome lacked docks, the steamers carrying the Earps and other passengers were met by small boats that navigated to 30 feet from shore and then deposited the women on the backs of men who waded through the surf. Once on shore, the Earps got their first sight of the two-block-wide, five-mile-long city. The unpaved streets could hardly be crossed without a tumble into two feet of mud. Finding no suitable hotel, Wyatt and Josephine moved into a wooden shack on the “spit,” a few minutes away from the main street, slightly better than a tent.

Nome was treeless, and also sleepless. The air vibrated with the constant clamor of saws and hammers. Basic sanitation was almost nonexistent; sewage emptied into the river that was the only source of drinking water. Typhoid, bloody dysentery and pneumonia were common. A smallpox outbreak led to the opening of the first hospital—and a larger graveyard.

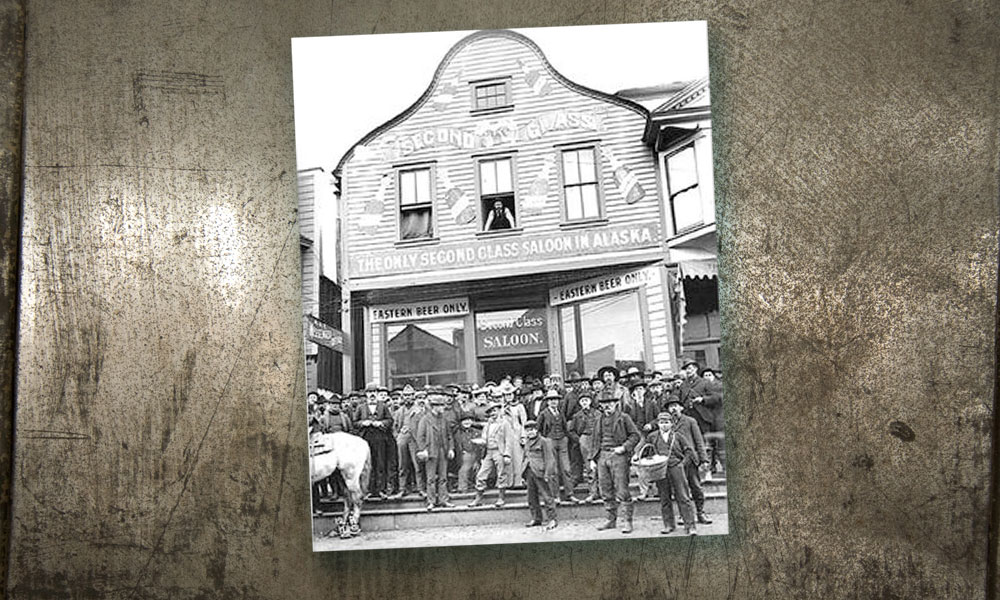

In partnership with Charlie Hoxsie, Wyatt built a two-story saloon called the Dexter. Prospectors needed to drink, to gamble and to enjoy the company of women. Wyatt knew how to make money, “mining the miners,” as he told his brothers. He had hopes of serving as Nome’s deputy marshal, but he was passed over for the position. He filed a few mining claims, but mostly devoted his efforts to his saloon. Trading on Wyatt’s celebrity, the Dexter was an immediate success, enjoying what newspapers called a “liberal patronage,” while amicably competing with Rickard’s Northern Saloon as the most popular spot in Nome.

Josephine rationalized that the Dexter was no simple bar: this “better class” saloon, served an “important civic purpose” as the clubhouse, town hall and forum where men could arrange political campaigns, transact business and enjoy social contacts. Into the doors of the Dexter walked any noteworthy visitor to Nome, from writer Rex Beach to mining engineer and future president Herbert Hoover. Rickard himself would become the most famous fight promoter of his day as the founder of the third incarnation of New York’s Madison Square Garden. “We met and hung out in saloons,” Wyatt observed. “There weren’t any YMCAs.”

To escape winter and outfit the Dexter more grandly, the Earps left on the Cleveland, one of the last steamers headed south, so crowded that Wyatt bribed passengers to secure a stateroom. The trip was a nightmare. First came the discovery that their bodies, clothing and furniture were crawling with lice. As they itched unmercifully, they encountered a storm so terrible that Josephine begged to get off the boat, though they were in the middle of the Bering Sea. They finally reached Seattle, nine days late.

They encountered a city with a single-minded focus; Seattle was Nome-crazy. The “Cape Nome Information and Supply Bureau” bombarded pedestrians with ads promoting Nome underwear, tents, medicine, even “Reed’s Blizzard Defier Face Protector,” which promised visitors to Nome that the “wearer can see, hear, breathe, talk, smoke, swear, chew, or expectorate just as well with it on as off.”

Local newspapers in Seattle and San Francisco noted the Earps’ return. San Francisco’s The Examiner reported that Wyatt was “making money perhaps faster than he ever made it before” and predicted “if business runs with him next summer as it did after his arrival in the camp, he will be able to retire with all the money he desires.” Seattle’s newspapers called Wyatt the “celebrated sheriff from Arizona,” though some, stirred up by Prohibition enthusiasts and competitive saloonkeepers, condemned him as a “bad man.”

With Nome now promoted as an exotic summer destination, as many as four ships a day left Seattle, filled to capacity with 700 people and loaded with thousands of tons of mining machinery and general merchandise. Other boats carried dismantled theatres, gambling halls, saloons, hotels and restaurants—everything needed to construct an “instant civilization.”

The Earps departed Seattle on the Alliance, with luxurious accessories for the Dexter in the hold. When their steamer stopped in Unalaska, Josephine was pleasantly surprised to run into her niece Alice and husband Isidore, on their way from Oakland to Nome, where Isidore hoped to sell clothes.

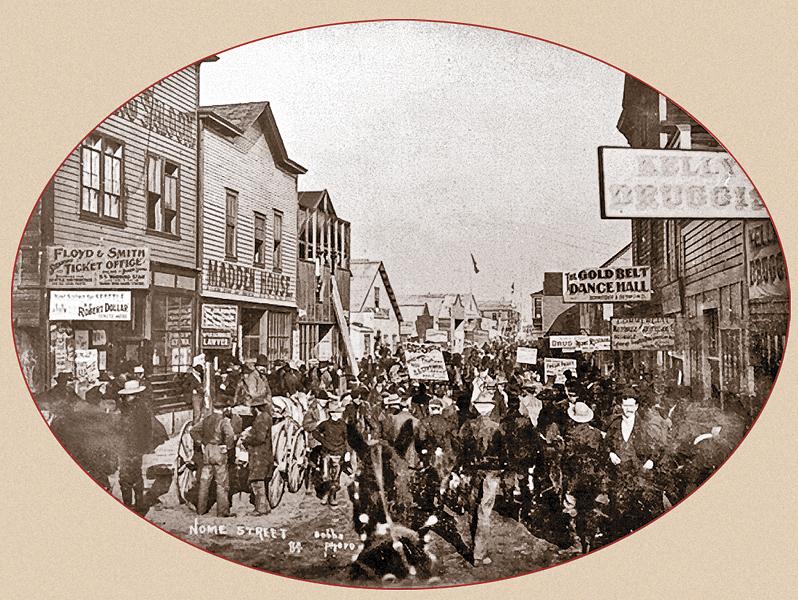

Nome 1900 was bigger and noisier. In place of the dories, a motley flotilla of barges, tugboats, rafts and rowboats hustled back and forth, loading and emptying enormous shipments of cargo. Watery roundups herded hundreds of cattle to shore. An army of Paul Bunyans plunged into the water to offer broad backs to Josephine and the other women to ferry them to land. For one brief summer, Nome became one of the world’s oddest seaports, where the last mile of freight delivery cost almost as much as it did to traverse the 2,000 miles from Seattle.

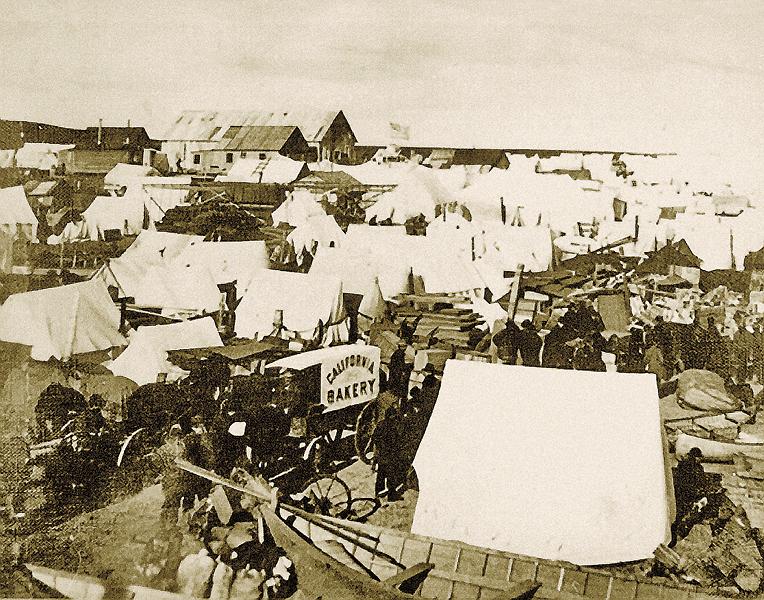

The beach was a scene of unimaginable chaos. The sand was barely visible beneath thousands of tents that almost touched each other, leaving the narrowest of passageways. Baggage and freight were piled high for a mile. Hundreds of dogs jostled furiously. Wagons hawked baked goods, clothing and mining supplies. Men carried trunks on stretchers or on their backs. Gold-panning contraptions churned in constant motion.

Within weeks, Nome grew to a city of over 20,000. But the beach, once “thick with gold,” had reverted to prosaic sand. “The major business in Nome in 1900 was not mining, but gambling and the saloon trade,” reported the Seattle Intelligencer. “Downtown Nome was lined with nearly 100 saloons and gambling houses, with an occasional restaurant sandwiched in between.”

The Dexter consolidated its position as Nome’s preeminent saloon for liquor and gambling, now handsomely outfitted from the Earps’ winter shopping expedition. Sky’s-the-limit poker games ran rampant during the gold rush days; anecdotal evidence ranges from guys blowing $10,000 on a hand of poker to as high as $500,000 (although the latter is not as likely). Prizefighting became a central feature of sporting life in the saloons and a major moneymaker for Wyatt, who often refereed bouts at the Dexter himself.

Besides visits with Josephine’s family (her brother Nathan also came), the Earps enjoyed Nome with old friends from Tombstone, Arizona. John Clum, the former editor of The Tombstone Epitaph, assumed charge of what was, in the summer of 1900, the nation’s largest general delivery post office. He had been among the 1,500 who rescued survivors and recovered bodies from the “Palm Sunday” avalanche at Chilkoot Pass.

Tombstone diarist George Parsons arrived to scout for a mining syndicate, but he considered that summer the “worst tramp of my life.” Parsons often visited the Dexter, which he called the “biggest drinking and gambling place here.”

Clum remarked how their three-way reunion occurred when Nome newspapers carried the story of “Apache Geronimo Insane,” caricaturing the former warrior’s antics at Fort Sills, Oklahoma. Nineteen years before, the three friends had joined a scouting party on the trail of Geronimo. Now they were in Nome, having a “regular old Arizona time,” Parsons wrote in his diary. Clum recounted, “It seemed proper that we should fittingly celebrate this reunion of scarless veterans on that remote, bleak, and inhospitable shore—and we did.”

Although the Dexter was prospering, the summer of 1900 generated serious marital tensions between the Earps. When the Dexter opened second-story “club rooms,” Josephine, upset over the saloon’s ties to prostitution, told her family that the rooms were for “games of chance, not frolic.” She was also gambling heavily—and losing. Instead of betting on the horses—impossible in Nome—she indulged her fondness for card games. Wyatt was having affairs in Nome, Josephine later confessed to her biographer Mabel Cason. He also had dust-ups with the law. Wyatt and Josephine’s brother were taken into custody after trying to stop a drunken brawl in front of the Dexter; Wyatt pled guilty and paid his fines. Later on, a military policeman attempted to stop a fight at the Dexter. “While the soldier is doing his duty, he is assaulted and beaten by Wyatt Earp and Nathan Marcus,” reported the Nome Daily News on September 12, 1900.

As if the specter of Tombstone had been awakened by these arrests, Wyatt’s youngest brother, Warren, was shot to death in July in Willcox, Arizona. Newspapers were quick to link his murder to Wyatt and his role in Tombstone’s Gunfight Behind the O.K. Corral. Warren’s killing was an unwelcome reminder that even in remote Nome, the Earps could not escape the past.

Nome was racked by political scandals and natural disasters that summer. Hurricane-force winds and rain kicked up waves that invaded Front Street and swept buildings into the ocean “in one tangled mess,” described George Parsons. About 100 people died. In her only recorded act of civic engagement, Josephine collected money for storm victims.

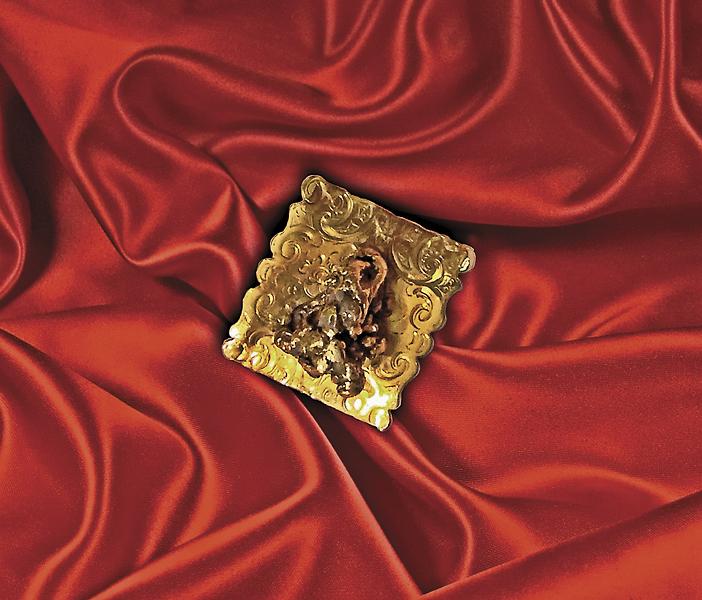

The storm and scandals of 1900 were the last straw for many miners. As the temperature began to drop, the stampede was on again, only the direction had reversed. Everyone wanted to go home. Most adventurers left poorer, sadder and probably no wiser. “My family stayed up in Alaska about a year, then they came back,” Josephine’s grandniece (daughter of Alice) recalled. “They didn’t get rich. I have a gold nugget that my father dug out of the mines, that I wear as a clip.”

Wyatt sold ownership of the saloon to Hoxsie and transferred the Earps’ mining claims to Josephine’s brother Nathan. The Earps made some $80,000 (more than $2 million today). When the Earps boarded the SS Roanoke in the fall of 1901, Wyatt reportedly said, “She’s been a good old burg. Mighty good to us.”

What happened to the Earp fortune from Nome? Motivated by the thrill of making a fortune, rather than by the fortune itself, the couple speculated on mines, started businesses, lent money to family and friends, and gambled enthusiastically. Their marriage survived, but their savings drained away, and they relied on a subsidy from Josephine’s rich sister. Wistful about Alaska, Josephine even considered a return trip, writing, “I am just in for it, as I do want to find a good gold mine. And I think that’s the country.”

But Nome’s greatest days as a mining sensation were over, and the Earps were aging. For most of Wyatt’s last decade, the couple lived frugally, shuttling between a one-room rented bungalow in Los Angeles and an isolated desert campsite where they slept under the stars. Theirs was a life of adventure, and a tale of the American frontier.

Ann Kirschner is the author of Lady at the O.K. Corral: The True Story of Josephine Marcus Earp and the university dean of Macaulay Honors College at the City University of New York.

Photo Gallery

In these never-before-published photos, Josephine’s niece Alice “Peggy” Cohn Greenberg, who visited the Earps in Nome in 1900, is shown in her plaid cape outside the Cape Nome newsstand.

– Courtesy Gary Greene Collection –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Carrie M. McLain Museum collection, Nome, Alaska –

– Courtesy Fred Agree Collection –

– Courtesy Library of congress –

The summer of 1900 nearly destroyed Nome. As the Bering Sea churned (1), from gusts reaching 75 miles per hour, waves invaded Front Street (2) and pushed cabins aside like bulldozers (3).

– Courtesy Carrie M. McLain Museum collection, Nome, Alaska –

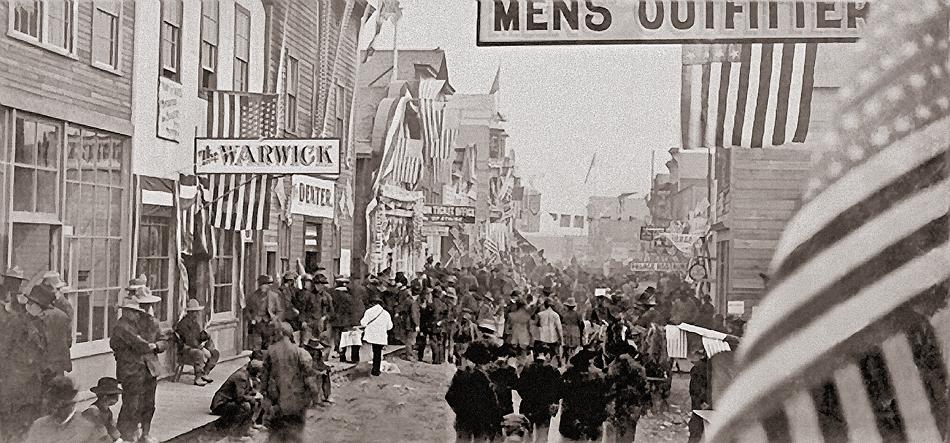

By 1900, the streets of Nome were filled with throngs of people. In the photo above, you can see the Dexter saloon that Wyatt Earp owned along with Charlie Hoxsie.

– Courtesy Carrie M. McLain Museum collection, Nome, Alaska –

– Courtesy Carrie M. McLain Museum collection, Nome, Alaska –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –