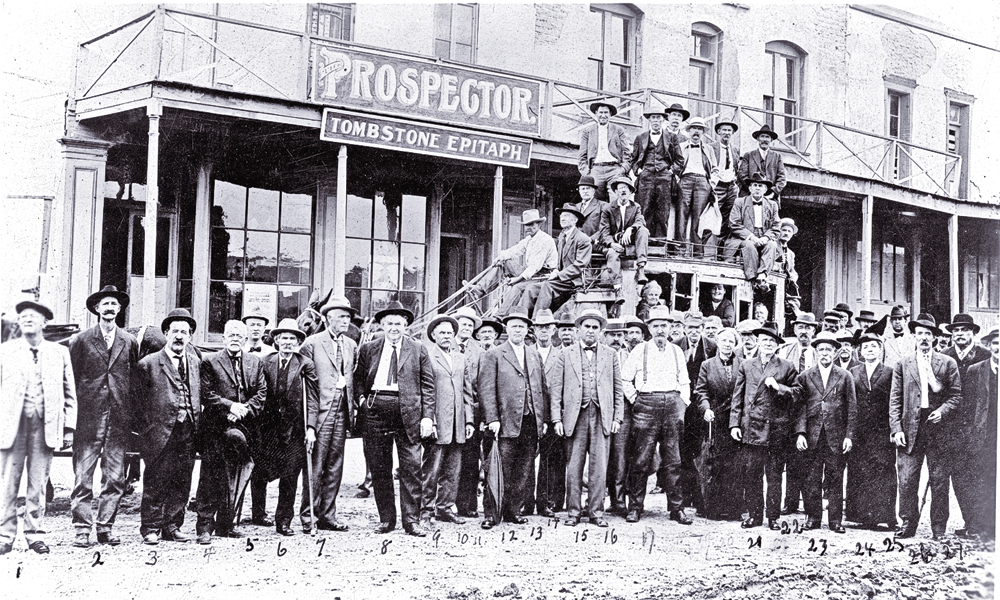

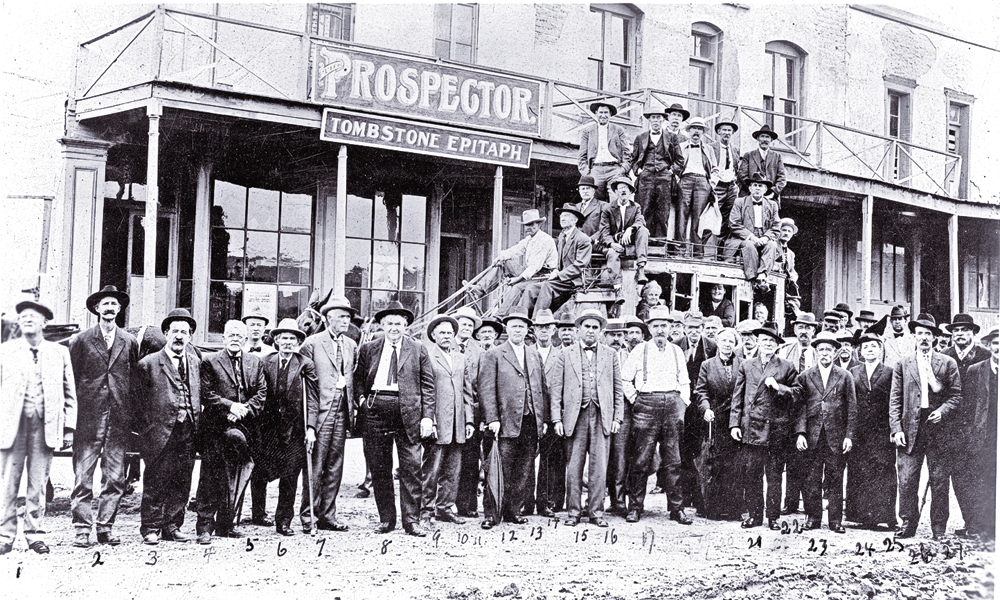

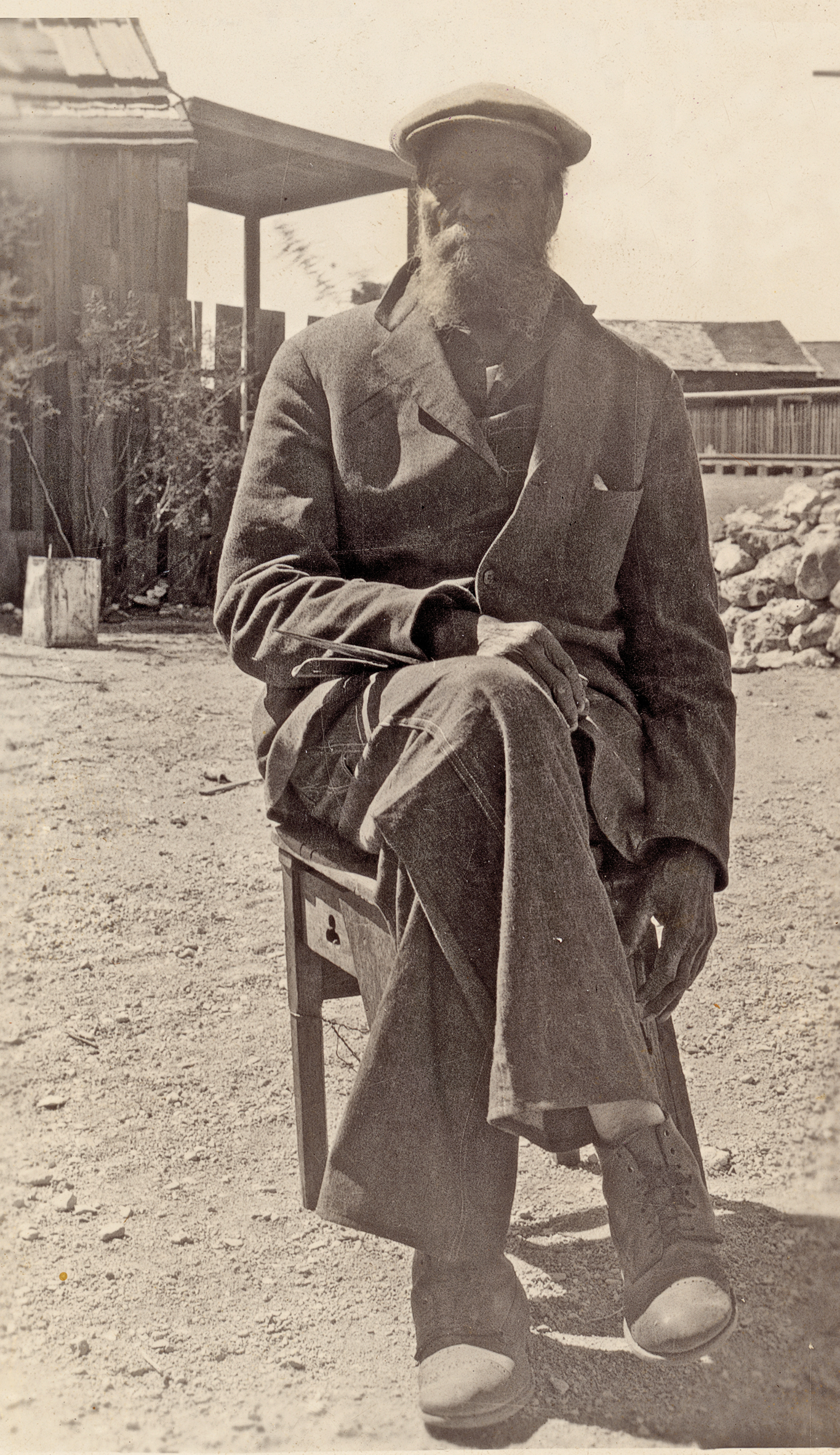

– Courtesy Arizona Historical Society –

In the spring of 1896, during the manhunt for the Apache Kid, Arizona’s most wanted, Tombstone surveyor H.G. Howe recommended to Sen. William M. Stewart a man who could track down the renegade:

“[Jim] is well acquainted with these Indian trails, knows where the Kid has his supplies sent, and has laid in ambush and watched the Kid come down to a spring to water his horse and drink himself. He says he can go out now with a few selected Indians and capture the Kid…. If the Kid was captured it would be a great relief to all of the settlers and prospectors in the Territory.”

Former U.S. Army scout Tom Horn was to join Jim Young, but the two never took to the field after the fugitive who was accused of killing at least two men, if not more. The Apache Kid escaped from justice, and his fate remains unknown to this day.

But what of Young, the black man originally at the center of an unfulfilled plan to apprehend the scourge of the border?

By the late 1870s, he rode west to Arizona with his former boss, the diminutive, but tough, no-nonsense “Texas” John Horton Slaughter. Standing over a head taller than Slaughter, at more than six feet, Young had been enslaved during the antebellum era, joined the regular army as a Buffalo Soldier after emancipation and then became a jack of all trades when he left the military.

When Young reached Arizona, he staked a mining claim for himself. When “Buckskin” Frank Leslie tried to grab Young’s diggings, he picked the wrong would-be victim.

– Courtesy Arizona State Archives –

Armed with a shotgun, Young challenged the bad man to leave. Leslie retorted that he had only come to help after hearing some folks intended to seize Young’s mine.

Leslie withdrew. Another time, when he found Young in a store, he almost shot his foe in the back. But the shop owner screamed, foiling the plan. Leslie claimed he was merely examining his six-gun. He never bothered his target again.

Young became a fixture around Cochise County and, according to the Tombstone Republican of September 15, 1883, he even turned to boxing. He went four rounds with pugilist Neil McLeod, besting his opponent despite a weight disadvantage of 10 pounds.

In October 1929, Tombstone recognized Young as one of its few remaining residents from its halcyon days of the Earps. He rode in the town’s first Helldorado Days Parade. By then, this fixture of Cochise County had relocated to Tucson, where he remained until his death on January 19, 1935. The Tombstone Epitaph reported he died at the age of 102!

Regrettably, the final resting place of this unsung frontiersman in Holy Hope Cemetery is unmarked, despite the fact that he, as the Epitaph reported, led “one of the most colorful of the lives of Arizona pioneers.”

John P. Langellier received his PhD in military history from Kansas State University. He is the author of dozens of books, including Fighting for Uncle Sam: Blacks in the Frontier Army, published in March 2016.