Even an everyday call to investigate cow stealing could spark violence that catapulted a Texas Ranger into the halls of death. This first look at Bob Alexander’s latest tome brings you the story of a brave man caught in the crossfire of King Ranch borderland politics—William Emmett Robuck, the first Ranger Force enlistee to be murdered at the Rio Grande’s edge.

Even an everyday call to investigate cow stealing could spark violence that catapulted a Texas Ranger into the halls of death. This first look at Bob Alexander’s latest tome brings you the story of a brave man caught in the crossfire of King Ranch borderland politics—William Emmett Robuck, the first Ranger Force enlistee to be murdered at the Rio Grande’s edge.

William Emmett Robuck’s genealogical family tree was fashioned from sturdy oak. Service in the Confederacy had claimed the life of his paternal grandfather. Emmett’s father, Elias, was a first-rate stockman, having early on gathered and trailed cattle into the faraway Rocky Mountain country while but a lad of 16. Emmett’s uncle, Tully Robuck, likewise was a Texas cattleman from Caldwell County southeast of Austin.

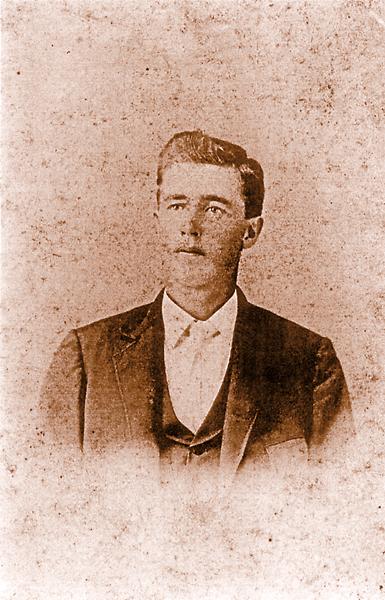

Emmett came into the world on July 27, 1877. Tallying the number of Whitetail deer he bagged or weighing the strings of catfish he pulled from the San Marcus River cutting through Caldwell County is unworkable. There are quantifiable truths, however. As he marched toward maturity, Emmett became quite handy with firearms and morphed into a top-hand cowboy, though he preferred calling himself a stockman. As an adult, he stood just under six feet tall, looking out from beneath his sweat-stained Stetson with steel-blue eyes. Emmett sandwiched between whetting his outdoor skills the classroom art of learning to read and write. He also developed the ability to speak Spanish.

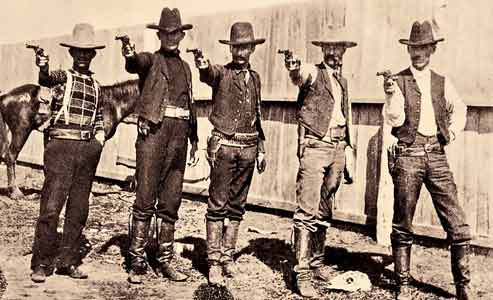

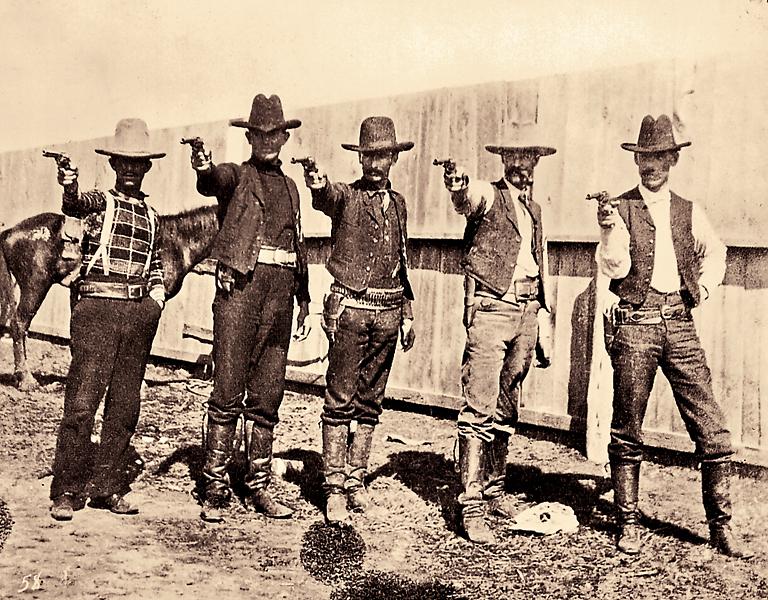

His bilingual ability would serve him well in his newfound job. At 23, Emmett became a Texas Ranger—a South Texas Ranger. Emmett had enlisted in the Ranger Force’s Company A, captained by James Abijah Brooks, and was assigned to a detachment at the extreme southern tip of Texas near Brownsville, Cameron County. Company A headquarters was 100 miles north, in Alice, 45 miles due west of Corpus Christi.

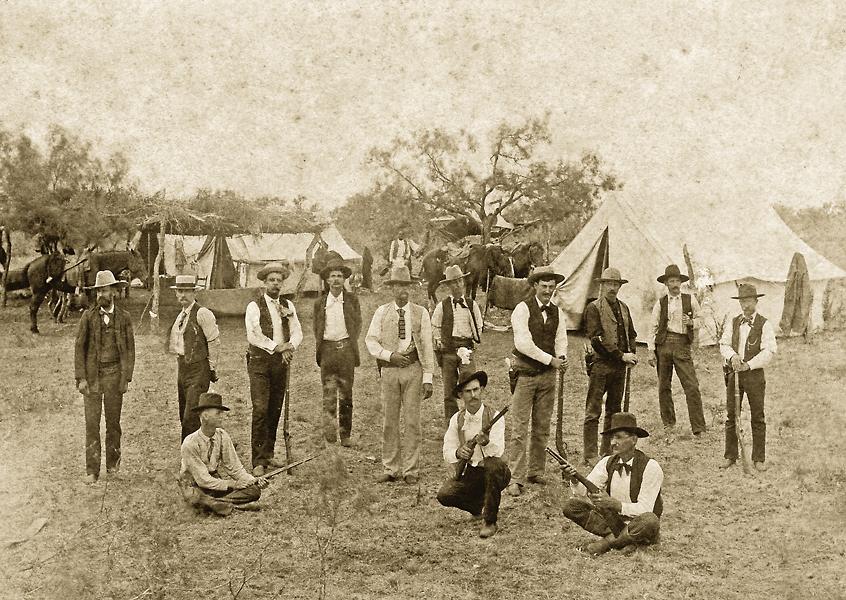

Much of the sparsely populated country between Alice and Brownsville—sometimes called the Wild Horse Desert—was dominion of the legendary King Ranch. There was an extraordinary linkage between South Texas’s gigantic King Ranch and the Texas Rangers. The understanding, though not reduced to writing, was reciprocal. The Ranger management team in Austin and its allied elected officials could count on King Ranch hierarchy to come through in times of political or pecuniary crisis. Likewise, when needed or perceived to be needed at the King Ranch, Rangers would answer the call, riding to the rescue, saving the day with Colt’s six-shooters at the hip, Winchesters in saddle scabbards and warrants of authority in hand.

The accord was not necessarily inappropriate. Cow stealing was cow stealing, no matter who owned the cow. During the springtime of 1902, most especially in the gargantuan El Sauz (sometimes El Saenz) pasture stretching to near the Cameron County line, sharp-eyed King Ranch bookkeepers and well-seasoned vaqueros noticed the herd was lessening—rather than growing. Cow thieves were about. Rangers were needed.

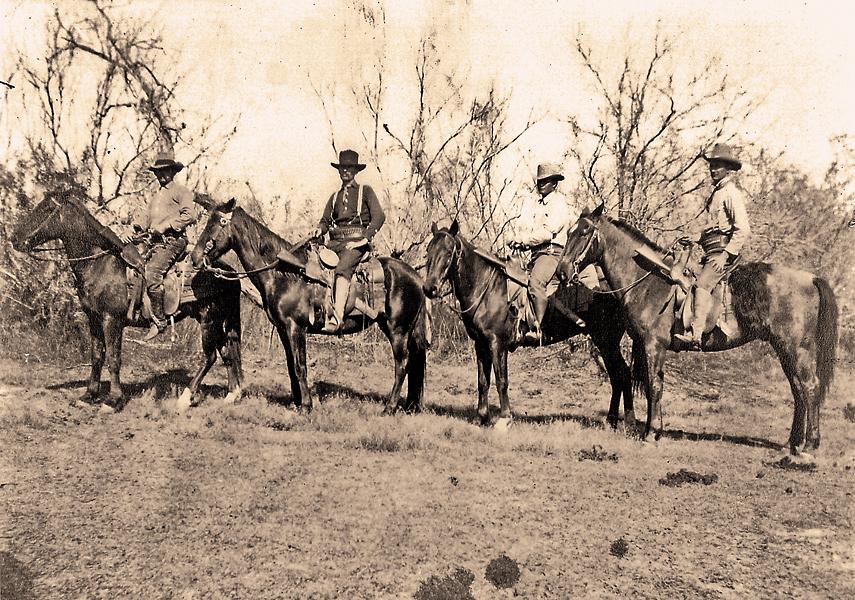

Captain Brooks was in receipt of a telegram—from the governor: “Send three Rangers to the King Ranch and investigate.” Riding from camp near Brownsville on May 15, 1902, Sgt. A.Y. Baker and Pvts. Harry J. Wallis and Emmett Robuck sallied forth to make their inquiries and, hopefully, catch some cow thieves.

At the El Sauz pasture, they were joined by cowboy Jesse Miller acting as guide. The Rangers all so soon encountered Reyes Silguero, who claimed to be a King Ranch fence rider working the El Sauz. The Rangers were suspicious. Fence riders were tasked with riding the fence line. In this instance, Silguero was at a loss to explain what he was doing over three miles away from any fence whatsoever. Private Wallis would later swear: “We thought that he was there either as a spy for thieves or he was there looking out from some big unbranded calves.”

Fearing Silguero would warn any amigos carrying running irons and working the brasada looking for unmarked cattle to brand and claim, the Rangers were not hesitant with employment of an unsophisticated preventative tactic—a tough one, nevertheless an undeniably helpful technique. They handcuffed one of Silguero’s hands to a “small live-oak tree and went off about a mile looking for thieves.”

Perhaps it was a face saving measure, or perhaps it’s true, but as an afterthought, Ranger Wallis remarked: “Before going we gave him all we had to eat, going without anything to eat ourselves.”

Silguero spent a lonesome and uncomfortable night shackled to the tree. Rangers passed the night elsewhere.

Next morning, shortly after daybreak, the lawmen’s suspicions were again aroused. During their scout, they found several calves, all tethered to trees. The sign was easy to read. Cow thieves were roping and tying while they could, intent on returning and burning brands when their supply of catch-ropes was depleted. Then the hunt for unbranded calves to chase and catch would begin anew.

The El Sauz pasture was big and screened in spots by dense undergrowth. The Rangers separated.

Near nine a.m., hell popped. Sergeant Baker, alone, emerged from thick brush nearly riding atop Ramón de la Cerda, a man in his twenties, who was afoot with a hogtied calf on the ground before him. Both men were taken off guard.

Ramón jerked both of his six-shooters, one a .41, the other a .45. Ranger Baker threw up his Winchester. Two shots were fired—at the same instant. An old-time ex-Ranger stabbed at summing up the gunplay with dry wit: “Cerda killed Baker’s horse by shooting him in the left eye. A.Y. killed Ramón by shooting him in the right eye.”

Justice of the Peace Estevan Garcia Ozuña officiated at the inquest. Besides concluding that Ramón was dead, as was Ranger Baker’s horse, the magistrate noted that several unmarked and unbranded calves were tied to trees in close proximity to Ramón’s body.

Thoughtfully, during the after-incident excitement and legal hubbub, someone had the good sense to turn a key and unhitch Silguero from what apparently had proven to be an unbreakable and deep-rooted live-oak tree. In the absence of solid evidence, Silguero was set free.

Rangers Baker, Wallis and Robuck, as well as their guide Miller, were required to post a bond guaranteeing their presence should a county grand jury choose to return formal indictments. Subsequently, the Rangers and Miller were “no billed,” a legal action that miffed much of the Spanish-speaking population.

A not insignificant number of native South Texans, when Texas Rangers were mentioned, raised an eyebrow, cocked their head and spit. To them, Rangers were rinches, mounted and armed Texans hunting for “Mexicans” to kill. In the Lower Rio Grande Valley, many folks viewed even legit Texas Rangers as but rinches de la Kinena—Rangers of the King Ranch. In Brownsville, whether one heartily championed or totally damned Rangers typically split along cultural lines.

One particularly vocal fellow was Alfredo de la Cerda, teenage brother to the deceased Ramón. Alfredo openly threatened to kill Ranger Baker on sight. Alfredo’s heartfelt grief was understandable, though the threat was not smart.

Acrimony, big talk and vitriolic threats were not factors of too much concern to Company A’s Capt. Brooks. He was tougher than the proverbial boot and, in his eyes, so were his Texas Rangers: “My men are crack shots and I am not afraid of them getting the worst of anything.”

The swank was premature.

Secretly, five fellows on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande piled into a skiff, and a handsomely paid boatman piloted the shotgun-wielding men across the river, depositing them on Texas soil. Under the cover of darkness, they surreptitiously worked their way into position along the Santa Rosatia Road, about a mile from downtown Brownsville.

On the night of September 9, 1902, about 10 p.m., Sgt. Baker and Pvt. Robuck, accompanied by cowboy Miller, who had been in Brownsville with them attending court, tightened cinches, stepped into the stirrups and started for their campground sited in a pasture owned by Judge James B. Wells—about a mile from town near the Santa Rosatia Road.

Salty sea breezes gently wafted from the nearby Gulf of Mexico. Routine night sounds blended with conversational tones as the three horsemen plodded along, bantering back and forth, recapping the day’s happenings and conjecturing about the morrow’s courtroom agenda.

Suddenly, the white gelding Ranger Robuck was riding jumped sideways in response to the noisy blasts—in harmony, three shotguns had spoken. Miller’s horse stumbled, crumpled and hit the ground dead, throwing Miller, but perhaps saving his life. Sergeant Baker lurched in the saddle and doubled over, wounded in the back—but not mortally. Seemingly unscathed, Emmett sat upright on the horse as it traveled about 150 yards before he lifelessly toppled from the saddle, a dead man falling. Bushwhackers ran for the river, crossed and then snaked their way back across the Rio Grande into Brownsville.

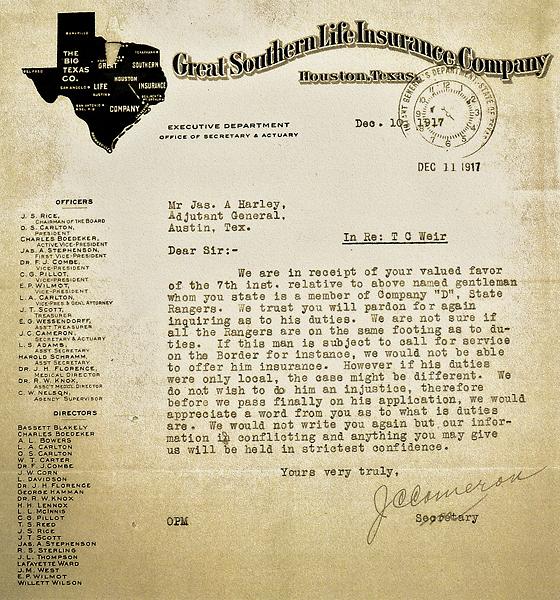

Due to District Court being in session, Capt. Brooks was in Brownsville too. He telegraphed Texas Adjt. Gen. Thomas Scurry: “Baker and Robuck waylaid on road to camp last night. Baker wounded. Robuck killed.”

In but short order—utilizing criminal intelligence furnished by an informant—Capt. Brooks soon had five suspects in the Cameron County jail, including Ramón’s little brother Alfredo. There was talk of mobbing the jailhouse and taking the prisoners by force, dispensing extralegal justice at the end of a rope. Stepping up to the best Texas Ranger tradition, Capt. Brooks assured any would-be lynch masters that he and his men felt it their duty to protect the prisoners and “would give our lives in their defense although we were fully satisfied that we had the right parties who were responsible for the assassination of our comrade.”

None chanced storming the jail.

Alas, the Blind Mistress of Justice was robbed of adjudicating the matter in a courtroom. An unknown executioner had exhibited his handiwork, murdering Herculana Berbier, the state’s star witness and snitch. Berbier’s blood and testimony had washed into a bottomless abyss.

Alfredo, after posting bond, continued his ranting about getting the scalp of a particular Texas Ranger. Though it may be politically incorrect to speak of reality, nonetheless there is a hard truism. In a world where men—good men and bad men—customarily attend to their everyday business carrying guns, it is sheer folly to think threats to kill will be lightly brushed aside as idle boasting. Altogether ignoring the man who says he will kill you, guilelessly thinking he won’t, is madness. Chaps spitting out death threats had best follow through—or dare not make a false move.

On October 3, 1902, on Elizabeth Street in downtown Brownsville, Alfredo wiggled the wrong way—or not? Sergeant Baker killed him, declaring he had made a suspicious move, as if grabbing for a six-shooter. ¿Quien Sabe?

Other reports indicate the dead fellow had been trying on a new pair of gloves. Alfredo was, as it turned out, unarmed.

From their safe quarters in Austin, Texas politicos saw that the wheels had come off in far South Texas, particularly in Brownsville. In the end, Sgt. Baker came legally clear of killing Ramón and Alfredo, but the Grim Reaper’s appetite for Texas Rangers had not been sated, not for those riding Lucifer’s Line: There were more on the menu.

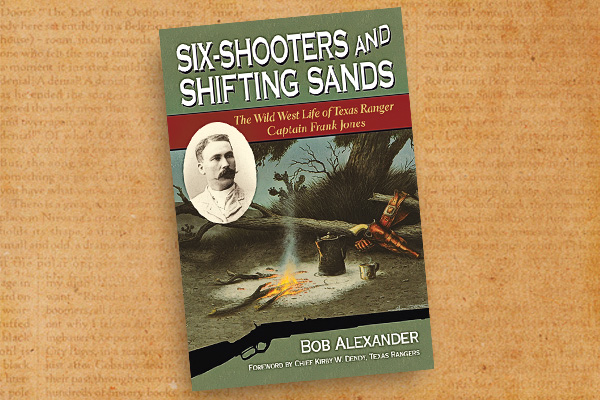

This edited excerpt is from Riding Lucifer’s Line: Ranger Deaths Along the Texas-Mexico Border by Bob Alexander, featuring a cover painting by Donald M. Yena. Published by University of North Texas Press, the book is due out in May 2013.

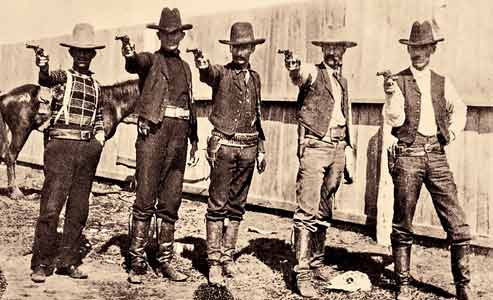

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Texas Ranger Hall of Fame & Museum Research Center in Waco –