In January 1863, Mangas Coloradas went to Pinos Altos, New Mexico, to seek peace with the United States. Other Chiricahua Apache tribal leaders had tried to talk him out of it, but Mangas persisted.

In January 1863, Mangas Coloradas went to Pinos Altos, New Mexico, to seek peace with the United States. Other Chiricahua Apache tribal leaders had tried to talk him out of it, but Mangas persisted.

Perhaps he was confident because he remembered the peace treaty he had signed in 1852 in which the U.S. pledged to “forever cease” its “hostilities” with the Apaches; to maintain “perpetual peace and amity” with them; and to arrest, try and, if convicted, punish any U.S. citizen who would “murder, rob, or otherwise maltreat any Apache Indian or Indians.” That treaty had led to a period of calm, but in 1863, the Apaches and the Americans were again in conflict.

This time, there would be no treaty and there would be no peace. Persuaded to meet alone with the Americans, Mangas was taken captive, tortured and assassinated.

Mangas Coloradas was chief of the Warm Springs Apaches, one of four bands of the Chiricahua Apache, whose homelands include present-day southwestern New Mexico, southeastern Arizona and northern Mexico. I am Mangas’s great-great grandson and chairman of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, the legal successor to the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache. I want to share with you the story of our people since Mangas’s assassination 150 years ago.

By the late 1860s, the U.S. began establishing reservations to teach Indians to farm and to convert to Christianity. Several reservations were planned for our people; a few were opened, but all of these ultimately closed and our people were moved to the San Carlos Apache Reservation.

The Warm Springs or Ojo Caliente Reservation in southern New Mexico was officially closed in 1877. It was the territory’s last to close and its last reservation designated for the Chiricahua Apache until one in southern New Mexico was proclaimed for our tribe in 2011.

The Apaches living on Warm Springs, including my grandfather Sam Haozous, were moved to Fort Apache at the San Carlos Apache Reservation in southeastern Arizona and placed in an area that would not sustain farming. My people experienced ration shortages, and they feared being arrested, attacked or killed. Those who most feared for their lives left San Carlos for Mexico.

Seeking to return to their people, tribal leaders Geronimo, Naiche and Chihuahua met with U.S. Gen. George Crook in March 1886 at Cañon de los Embudos in Mexico. They agreed to surrender on the condition that if they were held as prisoners, their families would join them and that they would all be freed after no more than two years. That night Geronimo heard he was to be executed upon his return to Arizona, so he, Naiche and several Apaches fled for their safety. When the others reached Arizona, they were shipped off to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, as prisoners of war.

After making this agreement, Gen. Crook received word that President Grover Cleveland did not accept the conditions of the Apache surrender. Crook was ordered to resume negotiations to accept only the unconditional surrender of the Apaches. Crook replied that this approach was not possible and asked to be relieved of his command in Arizona. He was reassigned and replaced by Gen. Nelson Miles.

Some of our leaders then went to Washington, D.C. to make sure that they and others who had not left San Carlos would not be punished for the things done by those who had left. They received a peace medal and boarded a train back to Arizona. Their train was stopped in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where they were held for one month. Then they too were shipped off to Fort Marion as prisoners of war.

In September, Geronimo, Naiche and the remaining group of Apaches who were still in Mexico met with Gen. Miles. They again agreed to surrender on the condition that if they were held as prisoners, their families would join them and that they would be freed after no more than two years.

Despite being ordered to accept only an unconditional surrender, Miles agreed to their terms, knowing that they would never surrender unconditionally. Geronimo and his crew, like those before them, were held captives as prisoners of war. They were stopped at Fort Sam Houston in Texas, while the U.S. investigated the terms of their surrender. After six weeks, the men in the group were sent to Fort Pickens, near Pensacola, Florida. The women and children were sent to Fort Marion.

At the same time, every Chiricahua man, woman and child living at the San Carlos reservation was assembled and told that they were going to meet the President of the United States. They were taken to Holbrook, Arizona, and instead of meeting the president, they were shipped off to Fort Marion as well.

Displaced but not broken, my people maintained a strong desire and heartfelt hope that they would ultimately return to their New Mexico and Arizona homelands, a desire we still hold today.

Separating tribal families was already unbearable, but when the government took the Apache school-age children away from the women at Fort Marion and shipped them to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the term “prisoner of war” was taken to another level. Against the wishes of the children as well as the parents, children at the Carlisle school were subjected to intense assimilation and indoctrination in the ways of the “white people,” which was assumed to be in their best interest by government officials.

Many of the children became terribly ill and died at the school, hundreds of miles away from their mothers and fathers, and farther still from their homeland. The Apache deaths at Carlisle began to reflect negatively on the school. For fear of the school’s reputation, a plan was devised. The moment an Apache child began to show signs of death from illness, they were put on a train and shipped back to their parents, thus avoiding, at least technically, the record of a child’s death at the school.

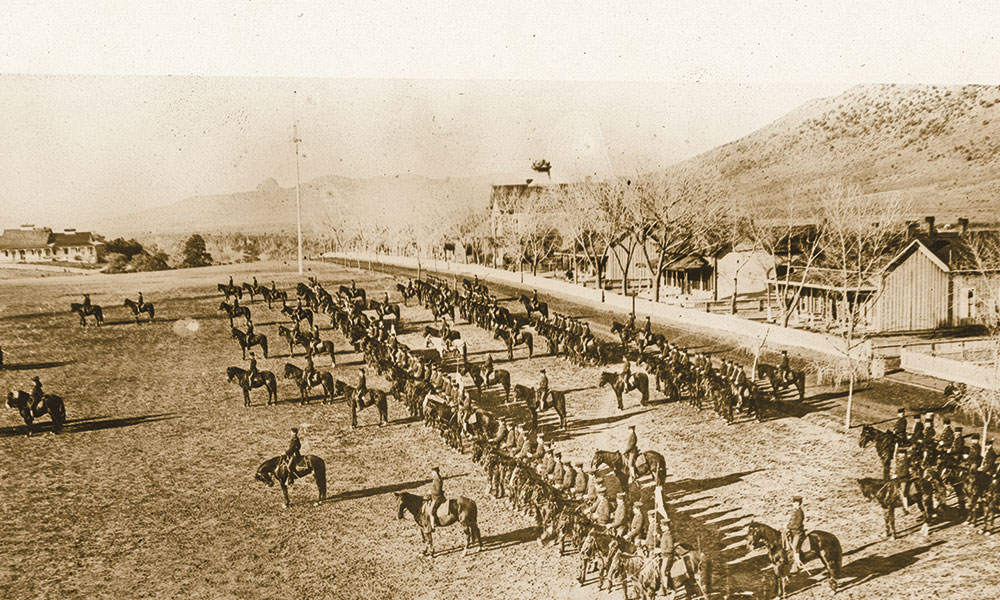

In 1887, tribal members were moved farther inland and consolidated at Mount Vernon Barracks near Mobile, Alabama. Families were reunited, but many of them were dying of disease, spurring debate in Congress toward the idea that the Apaches should be returned to an area with a more favorable climate.

Politicians in Arizona and New Mexico opposed repatriation of the tribe to any portion of its aboriginal territory (not unlike recent objections by today’s politicians). Instead, in 1894, Congress decided to move the tribe to the Fort Sill Military Installation in Oklahoma. Tribal members were told Fort Sill would be their home from that point forward. They were encouraged to make their lives at Fort Sill, so they started farming and ranching, trying to create a “normal” life, though in their hearts they knew nothing would ever be normal.

My ancestors believed that when Geronimo passed away, the key political reason we were being kept as prisoners of war would pass with him. Any politician who wanted to release these Apaches would have been branded as “soft on crime,” as if Geronimo was a criminal. Sure enough, after Geronimo died in 1909, the U.S. had no rationale to keep us as prisoners.

Today, Fort Sill Apaches look back on the centennial of the initial release of the Chiricahua Apache prisoners of war in Oklahoma. We had been promised that Fort Sill would be our reservation, a promise broken by the government when it removed the Apaches from Fort Sill. This, after we had become self-sustaining as farmers and highly successful as ranchers, boasting perhaps the finest herd of cattle in the U.S. at the time.

All told, our people endured captivity as prisoners of war for 28 years. When the tribe surrendered in 1886, the U.S. captured 515 Apaches. By the time of our release in 1913, only 261 of us were left—even though we had families born in captivity.

In 1913, one group left the tribe to join the Mescalero Apaches in southern New Mexico. This was a condition of their freedom. The rest of the tribe, including my grandparents and their first daughter, remained at Fort Sill as prisoners of war, pressing the U.S. to keep its promise. In 1914, they too were removed and were placed on individual allotments in Oklahoma.

In the 1940s, our tribe filed claims with the U.S. for the imprisonment and the loss of our land. The imprisonment claim was rejected under procedural grounds. The land claim was settled in 1973, when federal courts determined that our tribe was the legal successor to the Chiricahua and Warm Springs Apache Tribes, and that our legally defined homelands comprised nearly 14.8 million acres ranging from the Rio Grande in southern New Mexico west into southeastern Arizona.

In order to manage the compensation for this lost land, we were encouraged to organize under a tribal constitution. The two remaining bands, the Chiricahua and Warm Springs, formed a constitution in 1976 and chose the name Fort Sill Apache.

Although our tribe’s current name reflects our people’s time as prisoners of war, our hearts resonate with the dreams of our ancestors, the people of Mangas Coloradas, Naiche and Geronimo…the dream of returning to our homeland.

Jeff Haozous is the Fort Sill Apache tribal chairman. Visit FortSillApacheNewMexico.com and the tribe’s facebook and twitter feeds to learn more about

Fort Sill Apache history.

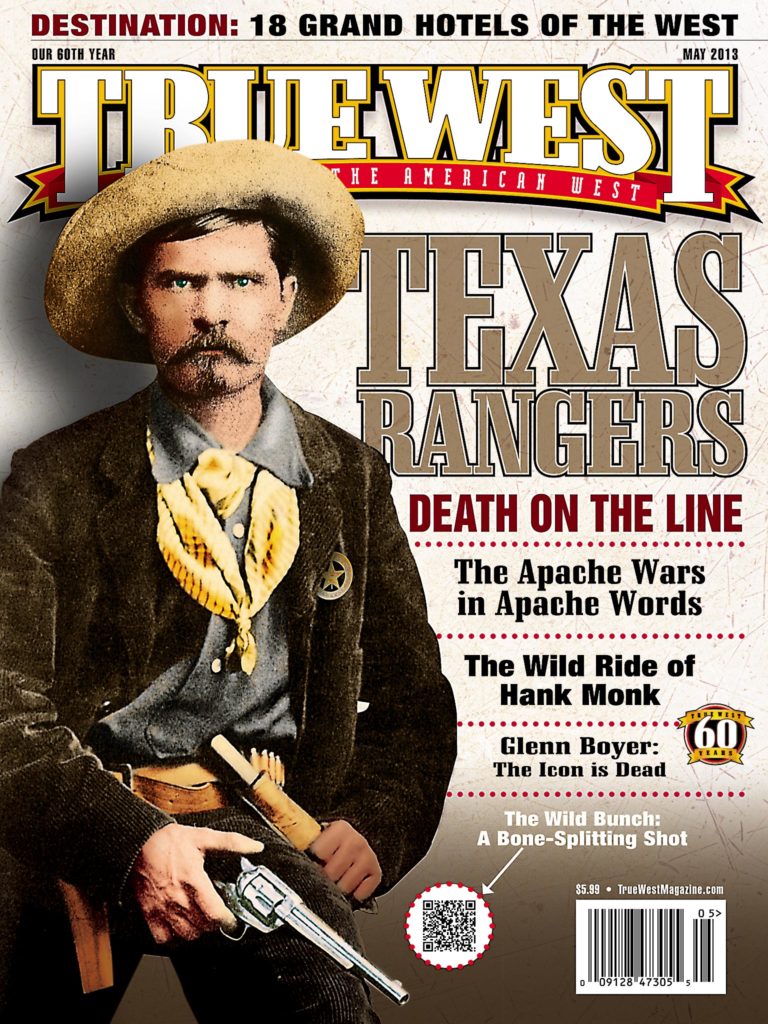

Photo Gallery

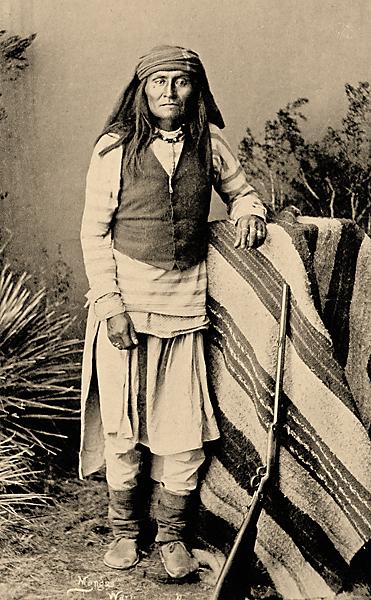

– Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution P06772 –

Gouyen

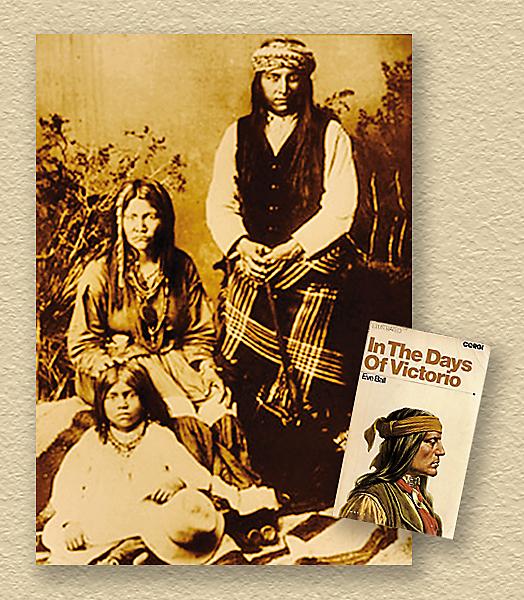

Legend has it that Gouyen avenged the death of her husband who was killed by Comanches. She infiltrated a Comanche camp and spotted a chief dancing a victory dance around a bonfire, with her husband’s scalp hanging from his belt. She seduced this man, killed and scalped him and ultimately delivered his scalp to her in-laws. Gouyen later remarried and is shown here with her second husband, Apache warrior Ka-ya-ten-nae, and her son (from her first husband) Kaywaykla. Gouyen died a prisoner of war at Fort Sill and she is buried at the fort’s Apache cemetery. Her son, James Kaywaykla, collaborated with Eve Ball to produce the book, In the Days of Victorio, hailed as a classic in Apache literature.

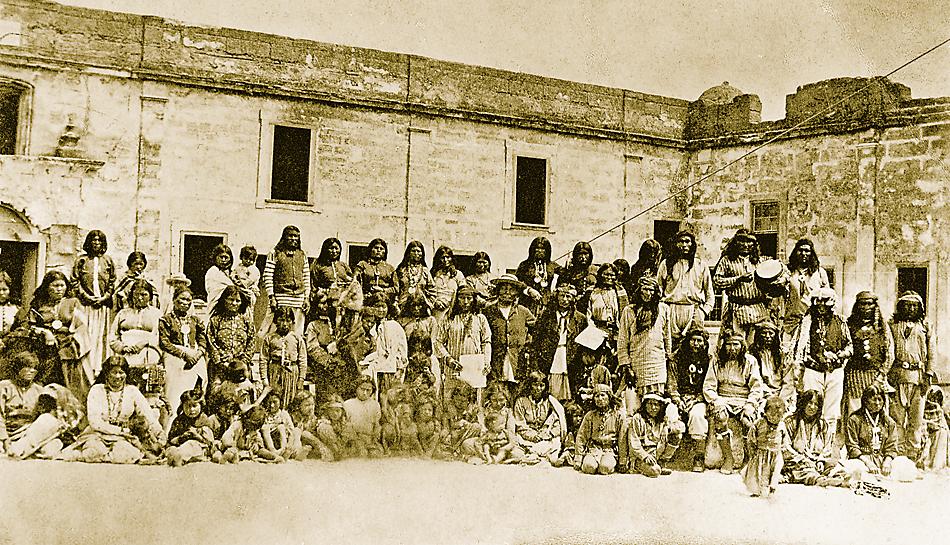

Lozen

Chief Victorio’s sister, Lozen, who he credited as his “right hand” and a “shield to her people,” never made it to Fort Sill from the Mount Vernon Barracks prisoner of war camp in Mobile, Alabama; she died of tuberculosis. She is credited as being with Geronimo and his band when they surrendered in 1886 (bottom row, third from right), but some Apache historians dispute this.

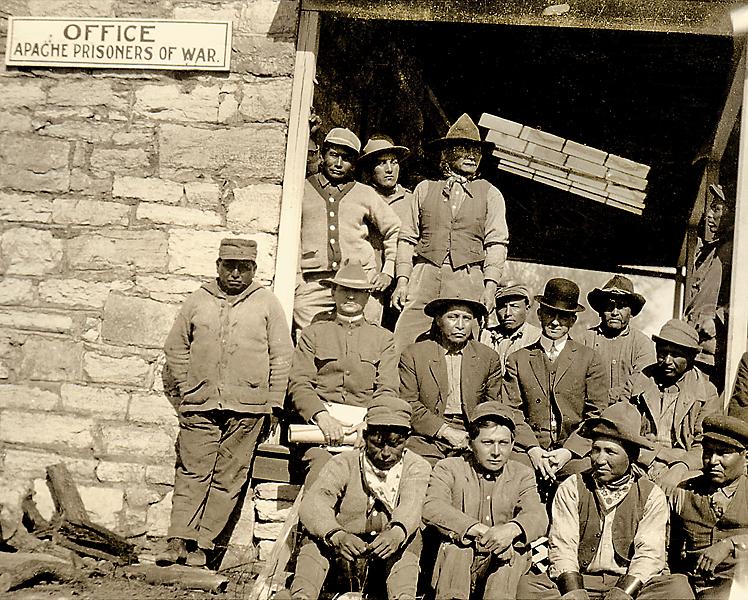

– Courtesy Fort Sill Apache Tribe –

– Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution 09508 –