For many American Indians, events of the past—even the distant past—are as real and present as something that occurred yesterday.

For many American Indians, events of the past—even the distant past—are as real and present as something that occurred yesterday.

The Sand Creek Massacre is one of those. For one church denomination, that long-ago tragedy still resonates today.

On November 29, 1864, some 700 Colorado militia attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho camp. An estimated 150 Indians, about two-thirds of whom were women, children and old men, were killed. Soldiers mutilated the dead and took some body parts as “trophies” for later display in Denver saloons and theaters.

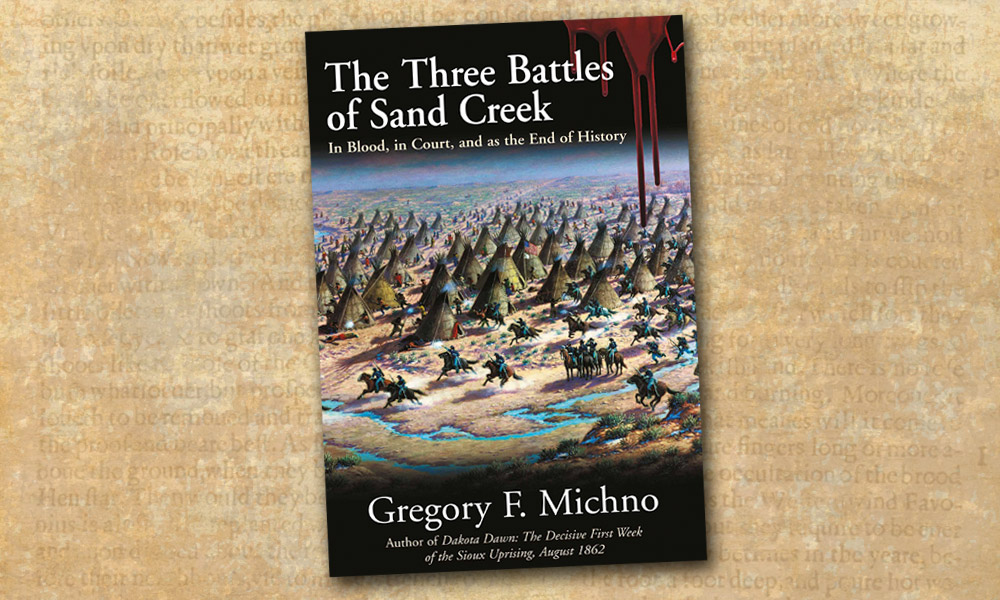

Militia leaders initially proclaimed the incident to be a great battle victory. But press and government investigations soon showed otherwise. Two of the militia officers—who refused to fight at Sand Creek—said the attack was committed against unarmed civilians. The soldiers had even ignored an American flag and a white flag flown over the Indian lodges. (In fairness, Gregory Michno, in his book Battle at Sand Creek: The Military Perspective, disputes many of these long-accepted details and states the incident was a real battle—albeit with atrocities committed afterward by the soldiers.)

Sand Creek had ramifications for two principles who lost their positions: Colorado Territorial Gov. John Evans, who authorized the action, and Col. John Chivington, who ordered and led the attack. Evans remained a highly

respected Colorado businessman, while Chivington drifted for the remaining 30 years of his life.

Ever since that terrible day, the event has brought forth theological fallout. That’s because “Fighting Parson” Chivington had been an ordained Methodist minister prior to taking up the sword in 1861 to fight in the Civil War. Evans had been a lay leader in the Methodist church in Indiana, Illinois and Colorado. Both had been instrumental in founding the seminary that became the University of Denver.

The church saw its ties with men associated with a massacre as problematic. Practically every time Sand Creek was mentioned, Chivington was identified as a Methodist pastor.

In 1996, at a meeting of the church’s global representatives, the now-United Methodist Church formally expressed regret for the Sand Creek Massacre, publicly apologizing for the “actions of a prominent Methodist.”

But within the church, an apology is not enough. The faithful must continually enact repentance—ultimately seeking a reconciliation with those who have been wronged and with God.

Which is why, in 2008, the denomination authorized a $50,000 donation to the Sand Creek Massacre Learning Center, located at the site of the incident. In 2012, delegates approved a measure that supports the return of the Sand Creek tribes’ artifacts and human remains. In 2016, the global conference expects to hear a report disclosing the full Methodist involvement in the Sand Creek Massacre.

The Sand Creek killings still haunt a lot of people; it may do so for a long time yet.

That may not be the end of the church’s efforts. Rev. Stephen Sidorak Jr. says, “We will never get a grip on our need for repentance until we grasp the breadth and depth of the historical injuries sustained by indigenous ancestors and the lasting wounds inflicted upon their descendants.”

Mark Boardman is the features editor for True West and a local pastor in the United Methodist Church.