Considering all the guardian angels who have looked over the Galveston Railroad Museum for more than a quarter century, where were they in the early morning hours of September 13, 2008, when Hurricane Ike almost destroyed it all?

Considering all the guardian angels who have looked over the Galveston Railroad Museum for more than a quarter century, where were they in the early morning hours of September 13, 2008, when Hurricane Ike almost destroyed it all?

“We had about $180,000 worth of Lionel model trains donated to us—it was so elaborate, we called it our ‘ooh and ah’ room because that was the reaction when someone walked in, but we lost it all in the storm,” remembers Morris Gould, executive director of the museum in Galveston, Texas.

“We lost about 85 to 90 percent of our archives and artifacts in the storm,” he adds. “We suffered over $6.5 million in damages. We had eight feet of water inside the museum.”

Gould had tried to prepare for the coming storm. “I came in on Thursday when everybody was being evacuated, and a part-time ticket agent helped me button down the museum,” he says.

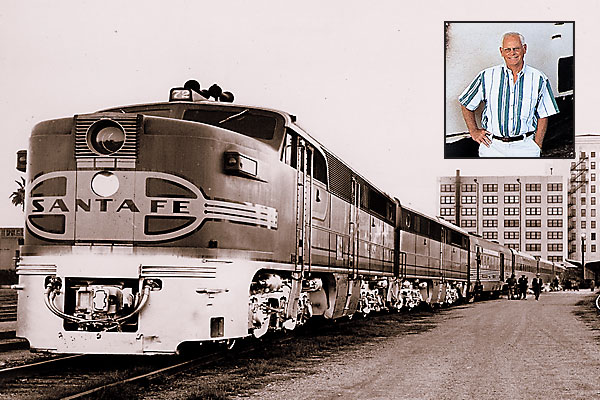

Gould personally “cranked up” antique locomotives and drove them to the highest point on the museum’s four-and-a-half acres. He laughs now, since the highest point was a difference of inches; at least eight feet ended up being needed for the treasures to escape damage.

The next time he saw the museum was three days later, and he remembers his heart skipping a beat as he looked at a parking lot covered with a thick muck of sea life. “It was absolutely overwhelming,” he says. “Everywhere you looked it was mass destruction. It’s hard to describe the carnage.”

Over 60 of his display cases “floated like corks in a swimming pool;” all his documents and records in 17 file cabinets were underwater.

Yet today, just three years after the storm, the museum is open again and starting to rebuild what it lost.

Volunteers helped with the clean up, and the board of directors immediately started plans to rebuild. Gould particularly lauds the help of FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency: “If not for FEMA, we would not be talking about this museum now.”

The agency granted the museum $5.3 million to rebuild, while donors—some large and many small—gave another $600,000. Even a child from Texas sent in $3; “It was really something how folks just opened up,” he says.

The Moody Foundation, which created the museum in the first place, pledged $100,000. Mary Moody Northern had not wanted to see the destruction of the 10-story Union Station that opened in 1932 and saw its last passenger train pull out in 1967. Northern—the museum’s first guardian angel—provided the seed money to purchase the depot. The roughly 9,000-square-foot museum opened on April 15, 1983.

Another guardian angel, Dr. Henry Reinfert of Austin, had been collecting rail cars and dining service since the 1960s. He donated virtually his entire collection to the museum.

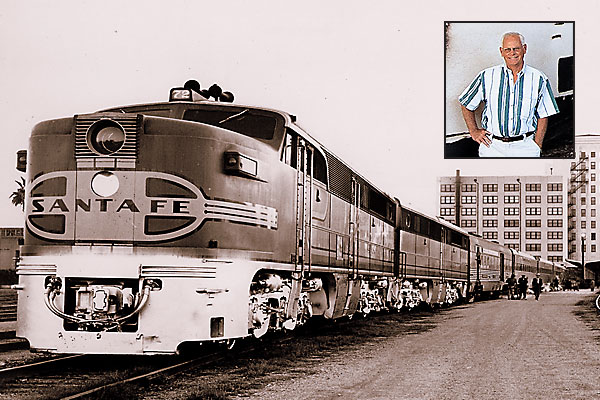

Gould, the latest of the guardian angels, volunteered at the museum when it opened in 1983, working on a steam engine. Two years later, he served on the board of directors. After retiring from his day job at an oil company in 2005, he became executive director in 2007. “That first year, the museum had a profit for the first time,” he says with pride—noting he had great help from the marketing director he hired, Sandi Cobb. “We had six figures in the bank, and we were just tickled with our success. ’08 was looking good, too, until Ike. But now we’re on the way back again.”

A “soft” opening of the museum took place on March 15. The mile-and-a-half track that offers locomotive and caboose rides is back. As the staff repairs and replaces what was lost, Gould is proud he can once again invite people to “Follow the tracks to Yesteryear at the Largest Railroad Museum in the Southwest.”