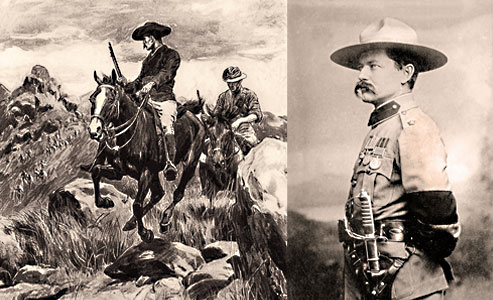

The harsh winter of 1882 was finally melting away as both the kid and his horse resembling starved scarecrows made their way down the snow packed Mogollon Rim in Arizona Territory.

The harsh winter of 1882 was finally melting away as both the kid and his horse resembling starved scarecrows made their way down the snow packed Mogollon Rim in Arizona Territory.

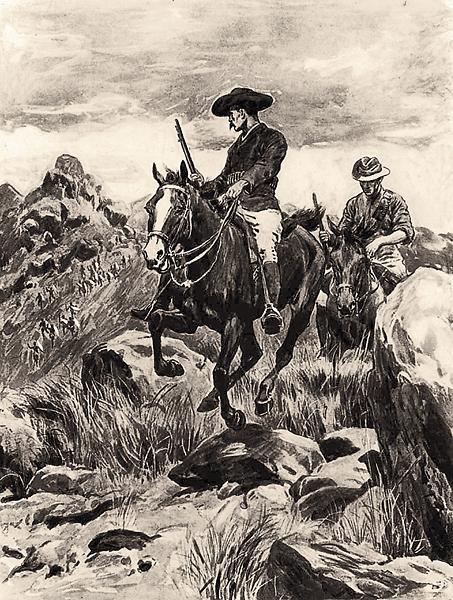

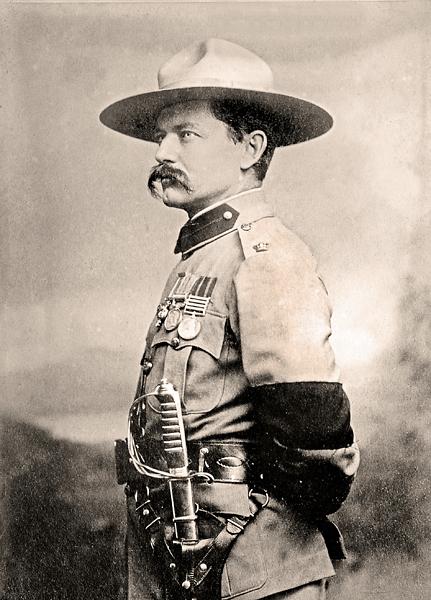

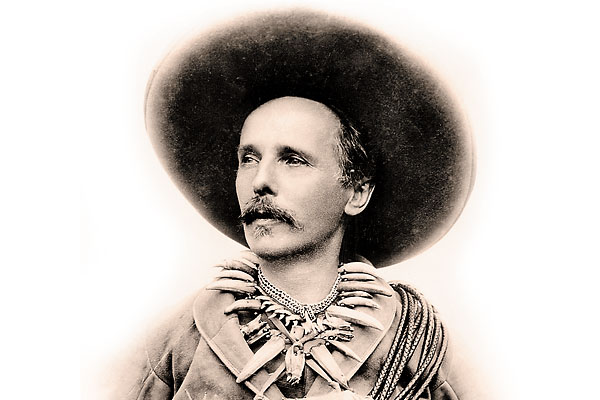

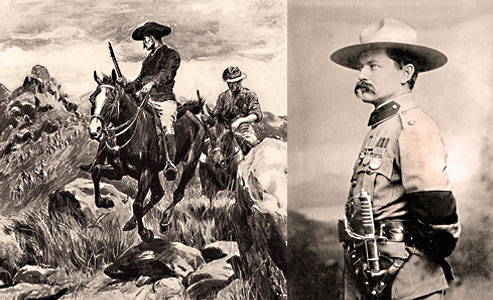

Frederick Russell Burnham wondered if he was going to make it. Only five foot four, with piercing blue eyes, 21-year-old Burnham had already been forged by the West. After being raised on a Sioux reservation in Minnesota during Little Crow’s uprising, he decided to fend for himself in California by age 12 after his father died.

He had always wanted to see Arizona. When his horse was stolen outside of Santa Fe, New Mexico, he walked the 500 miles to Prescott, Arizona, traveling at night to avoid the Apaches. From there, he scaled the Mogollon to winter in and search for gold.

Burnham would end his life’s journey a frontier legend in both North America and Africa. In Africa, his exploits led to him becoming one of the templates for the literary figure Allan Quatermain. In America, he was one of the gunmen Zane Grey wrote about in his account of Arizona’s Pleasant Valley War.

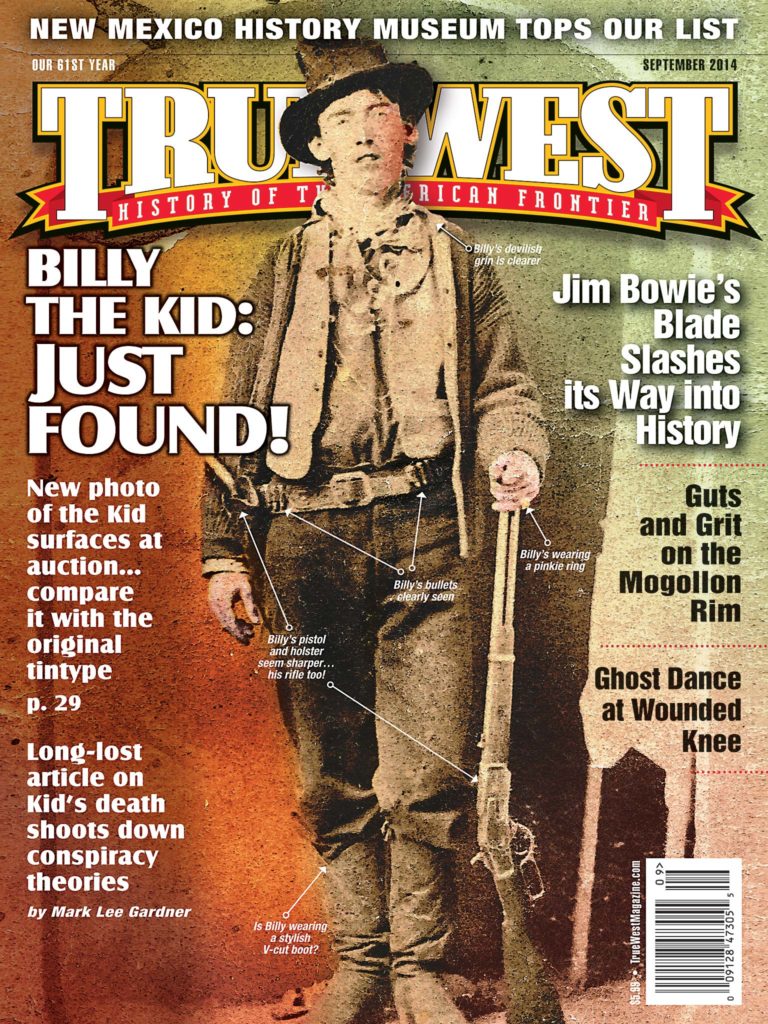

Guts and Grit on the Mogollon Rim

Burnham made it as far as the snows of the Mogollon Rim. Rabbit and lizard kept him alive as he roamed the Mogollon. Even in his desperately lost state, the young man kept an eye out for anything that looked like gold or silver.

An unusually hard winter cost Burnham all his supplies and nearly himself. He staggered down the southern side of the Rim into the Tonto Basin. Starving to the point where he might have to eat his horse,

he resembled a collection of bones in leather bags when he came across a lone homestead.

Heavy snow had also forced the Wells family off the Mogollon Rim after losing most of their cattle. Burnham and his horse were in such shocking physical shape that elderly Fred Wells took him in, feeding him from what little the family had.

An old-time buffalo hunter, Fred began instructing Burnham how to shoot. Burnham practiced firing his Remington Model 1875 with both his right and left hands, as well as off a horse at full gallop.

Burnham practiced shooting all the time. By 1884, after roughly two years of clashes due to rustling accusations on both sides and an undercurrent of racial prejudice against the half-Indian Tewksburys, a feud was heating up between cattlemen led by the Graham family and Jim Stinson and sheepmen led by the Tewksbury family. Isolated shootings were causing people in the basin to pick sides, something the Wells family was trying to avoid.

Then the cattlemen faction bought Fred’s bank note for money he had borrowed to build up his herd, as well as his IOUs at stores in Globe.

“I soon became conscious of a strange undercurrent of mischief at the round-ups or in the dance halls of Globe,” wrote Burnham, who was working in one of the area mines at the time.

The Dog Fight

Fred’s creditors let the rancher know he either sided with the cattlemen or lost his herd in foreclosure. But the old man would not bend.

Burnham offered Fred what money he had been able to save from working in the mines. Fred took it, yet the young man’s contribution barely made a dent into what the rancher owed. Fred then decided to drive his cattle up the Rim and hide them.

Burnham and Fred’s son, John, rode point and flank with the main herd, while Fred’s three daughters led the older stock. Sporting a double-trigger, long range buffalo gun, Fred rode into the brush, zigzagging while he scouted the area and kept his daughters covered.

Two deputies riding hard and fast out of Globe caught up to the daughters. They had come to seize their cattle. The young women shouted back that the cattle belonged to them and not their father. The tension caused a barking frenzy from the girls’ dogs, which alerted Burnham and John. They rode down, and when they saw what was going on, they also shouted at the deputies that they had no right to take the girls’ cattle.

One of the deputies dismounted, and one of the dogs bit him. The injured deputy drew down, shooting the dog dead. The unexpected gunshot surprised the three Wells girls, brother John and Burnham, who all drew on the lawmen. One shot was fired, and the deputy dropped dead.

The kill shot was from Fred, up in the rocks at a range of 800 yards. He had been trailing the deputies ever since he spotted their dust. “…yet it was in all likelihood a chance shot with his black-powder rifle,” Burnham wrote.

The other deputy threw his hands up in the air, surrendering. Old man Wells immediately grasped the situation. He did not want his children hunted down for the murder of a lawman. He convinced the deputy to tell the authorities that he had no idea who fired the kill shot. In exchange, the deputy could take some of the cattle back to Globe and the Wells would ride for the cattlemen when called upon.

Pleasant Valley Gunfighter

Inside the whirlwind of the Pleasant Valley family feud, Burnham found himself either in raiding parties shooting up sheep camps or on patrol riding heavily armed over open range. Men he encountered during the battles were slowly being picked off on the range or assassinated in Globe. The Pleasant Valley War would claim anywhere from 20 to 34 men killed in gunplay.

During a meeting in Globe, sheepmen pointedly discussed eliminating Fred and John, and the “unknown gunman” with his “Remington six-shooter belt.” They meant Burnham. Bounties for their capture were placed on all three.

Meanwhile Burnham delivered messages between the cattle barons, who were coordinating their raids, and various local politicians. He took precautions never to ride the same horse from one area to the next by keeping outfits in several Arizona towns, including Prescott, where he stopped to rest from time to time.

Burnham also gathered intelligence on the sheepmen. The gunman found himself portraying various roles—teamster, miner, big game hunter or prospector—as he spied out the open range.

He toyed with the idea of joining up with a hard-riding Kansan who had a plan to get out of Arizona and the feud altogether. The Kansan wanted Burnham to help him rustle cattle and horses from local mining camps for them to sell to the Curly Bill Brocius outfit in Tombstone. (At this time, Brocius and Ike Clanton were engaged in their famous feud with Wyatt Earp and his brothers.) His partner-to-be boasted that within six months, they would earn enough to leave Arizona in style.

Although tempted, Burnham turned down his friend. Shooting other gunmen as the feud progressed was one thing, but becoming a horse thief was crossing the line.

As the death toll mounted, Burnham found that every man he killed created a new feud. It was “not winner take all—but winner take on all,” as author Craig Boddington noted.

On the Run

Burnham wanted out of the war. He headed to Globe to seek counsel from a friend, Judge Aaron Hackney, the editor of the Silver Belt newspaper. When he rode into Globe, though, he did not realize bounty hunter George Dixon was trailing him. Dixon caught Burnham asleep in a cave, putting his Colt .45 against the young man’s temple and ordering him outside.

But Dixon, too, had been tracked. A White Mountain Apache named Coyotero shot Dixon through the heart as the two men emerged from the cave. Burnham took the opportunity to grab his Remington and fired back, killing Coyotero.

Burnham reached Hackney, who dressed him up in a disguise before turning him over to noted prizefighter Neil McLeod, who was willing to spirit Burnham to Tucson. The judge may or may not have known that the charismatic McLeod was one of the top smugglers in the Southwest.

Burnham fell under McLeod’s spell and began running coded messages for him between operatives, which forced Burnham to cross hostile Apache country. While riding for McLeod, Burnham went to meet John Wells at Dripping Springs and discovered one of his sisters there instead.

He found her there, with a swollen leg from the stub of a pine that had run itself through her calf when a bear had charged her mount. As Burnham treated her wound, she told him her father had died and that brother John had been sent off to serve time in Yuma Territorial Prison. Burnham flagged down a passing stagecoach. A couple dance hall girls from Tombstone’s Bird Cage Theatre were on board, and they said they would look after her.

Sensing that he was still being tracked, Burnham disguised himself as a freighter and made his way back into Globe. When he slipped into the judge’s house, he got a tongue lashing. Meeting the Wells girl had given away his presence in the Globe area. Burnham had to get out for good.

The judge sent Burnham to stay with friends in Tombstone. Before his arrival, Burnham had written, “Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder’s cause was all wrong…. I realized that I was in the wrong and had been for a long time, without knowing it.”

The Pleasant Valley War continued until 1892 with the murder of cattleman Tom Graham. Sheepman Edwin Tewksbury was the sole survivor of the feuding families. He and Burnham were among the last survivors of the range war to live into the 20th century, along with other notable participants who included Tom Horn, Commodore Perry Owens and Jim Roberts.

Burnham made good his escape by marrying his childhood sweetheart, Blanche, in Iowa. Yet his romance with Arizona was not over. He returned to scout for Gen. George Crook against the Apache and serve as deputy sheriff of Pinal County.

The Next Continent

In 1893, Burnham, believing the West had lost its adventure, took his wife to South Africa where he scouted for Cecil Rhodes in his conquest of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia) from Matabele tribesmen. He returned to North America to participate in the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon Territory and to lead archeological digs on the Mayan civilization in Mexico.

Two South Africa friends made Burnham a legend in his own time. Novelist H. Rider Haggard used Burnham as his template for his hero Allan Quatermain for the 1885 novel King Solomon’s Mines and dedicated three books to Burnham’s daughter. Robert Baden-Powell wrote down Burnham’s scouting techniques to be used by his newly formed Boys Scouts organization.

After a rich adventurous life scouting for two continents, Burnham died at age 86 at his home in California in 1947.

Mike Coppock is a published author of Alaskan history works. He currently resides in Enid, Oklahoma, and he teaches in Tuluksak, Alaska, part of the year.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Illustrated London news –

– Courtesy National archives of Rhodesia –

– All images true west archives unless otherwise noted –