“They say my bowie knife is keen to sliver into halves

“They say my bowie knife is keen to sliver into halves

The carcass of my enemy, as butchers slay their calves.”

These two bloodthirsty lines satirized American society in the “American Ballads” section that introduced the 1845 British Book of Ballads. Nine rhymes in this section mentioned the Yankee fondness for the bowie knife, then considered a necessary part of dress in America’s early 19th-century frontier.

James Bowie’s famed fighting knife, the origin of which remains shrouded in controversy, has been woven into the colorful fabric of American folklore. But what exactly is a bowie knife?

Some arms students feel that a bowie can be any sheath knife with a clipped point, regardless of size. Others deem it to be any large knife, regardless of blade shape. The rest feel that virtually all sheath knives produced from around 1830 through the end of the 19th century qualify as bowies. Serious collectors seek out vintage knives with a clip-point blade, recognized as the classic form of a bowie knife.

While historians may argue whether James Bowie, his older brother, Rezin, or knife maker James Black actually produced the first true bowie blade, James deserves credit for bringing the edged weapon to the forefront. While no one knows for certain if his original knife had a clipped point, we do know James carried a large, single-edged knife with a sharp, false edge at the back of the point, allowing for an effective backstroke.

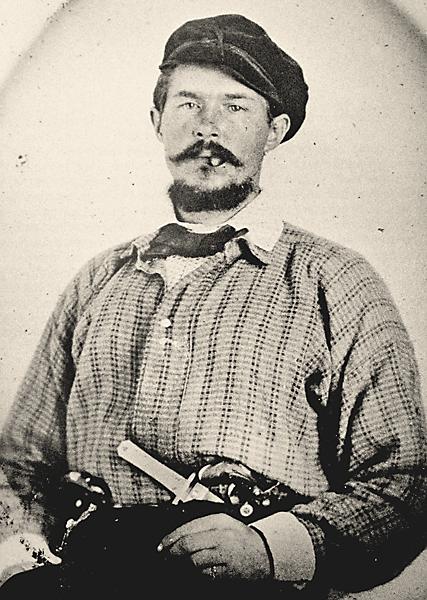

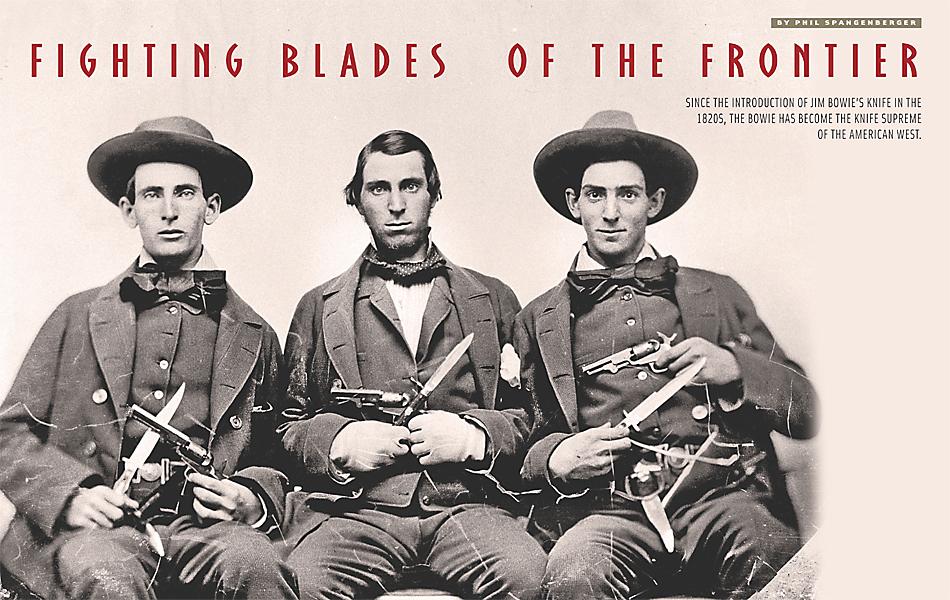

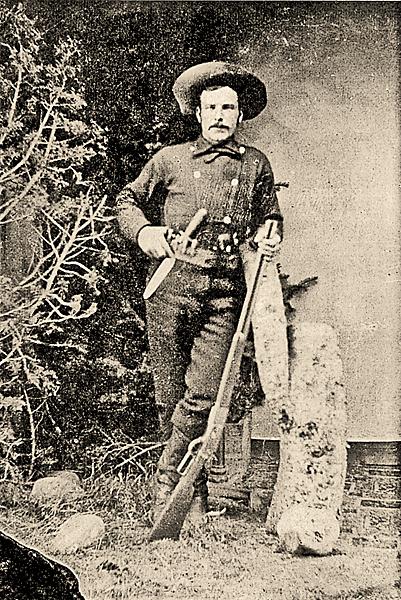

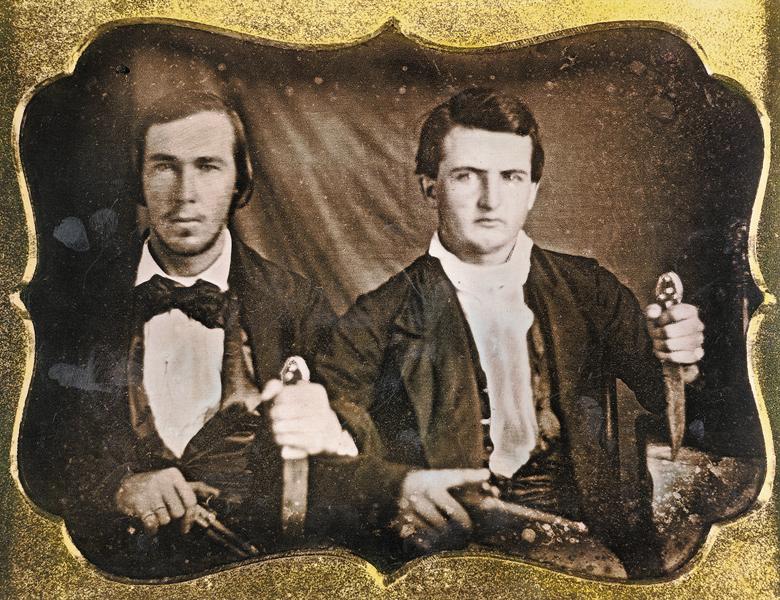

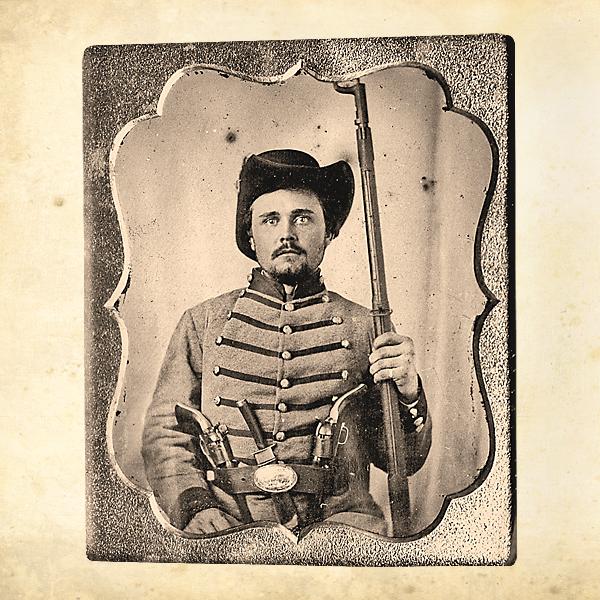

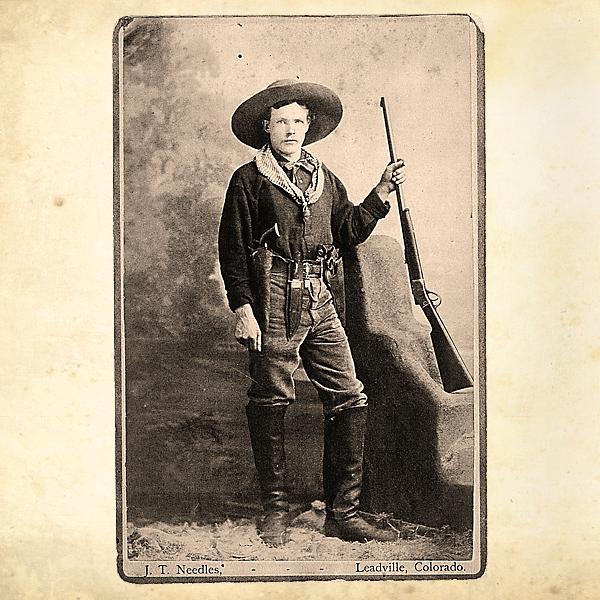

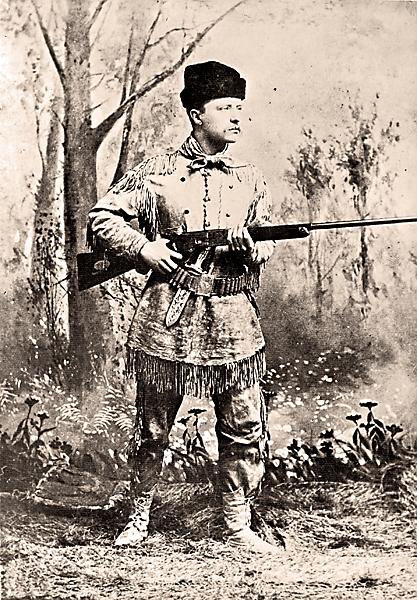

In the early 1800s, virtually every frontiersman packed some sort of edged weapon, largely because of the limitations and lack of surefire reliability of the firearms of that period. Regardless of whether one packed a pocket-sized folding knife, a medium-length hunting blade or a full-sized fighting weapon, a knife of some sort was essential to survival. Long before the advent of the bowie, blades of all sizes and shapes were commonly carried and were variously called long knives, rifleman’s knives, scalping knives, belt or sheath knives, dirks or the all-purpose butcher knives. Knives were quite simply a part of one’s everyday experience.

The Bowie Knife’s Bloody Entrance

The infamous Sandbar Fight along the Mississippi River on September 19, 1827, catapulted James and his knife to fame. The affair, which started out as a duel between two men, ended up as a bloody brawl between the aggrieved combatants, their seconds and comrades. James killed one opponent and badly wounded another, despite being seriously wounded in the chest, thigh and head. The murderous clash was reported in the local papers and picked up by others throughout the country, eventually spreading as far as Great Britain. Before long, James’s heavy bladed weapon became known as the fighting knife of the West. Both man and blade achieved such notoriety from this fight that the name “bowie” became a household word. The moniker was recognized as early as 1830, as evidenced by the December 24-30, 1830, advertisements for bowie knives in the Washington D.C. newspaper Daily National Intelligencer.

James’s fight was one of countless violent incidents involving knives in the years before the advent of reliable repeating firearms. From the Louisiana swamps to the “Bleeding Kansas” prairies and from the “Big Muddy” Mississippi River to the California gold fields, such blade-wielding affairs weren’t relegated just to backcountry campsites, bawdy saloons, gaming houses or riverboats. Knife fights even occurred in the state legislatures and the halls of Congress. Period accounts of those hardy souls who traveled the antebellum frontier offer evidence of the bowie’s popularity as a weapon of choice. For example, an 1836 issue of the Red River Herald of Natchitoches, Louisiana, published a couple months after James’s death at the Battle of the Alamo, declared that, quickly following the Sandbar Duel, “all the steel in the country, it seemed, was immediately converted into bowie knives.”

Further proof of the popularity of edged weapons in the untamed regions of America comes from Col. Edward Stiff, when he cited the lawless nature of the frontier and the prevalence of such weaponry in his 1840 guidebook The Texan Emigrant. “Perhaps about 3,000 people are to be found at Houston generally, and among them are not exceeding 40 females. Here may be daily seen parties of traders arriving and departing, composed too, of every variety of colour, “from snowy white to sooty,” and dressed in every variety of fashion, excepting the savage Bowie-knife, which, as if by common consent, was a necessary appendage to all,” he wrote.

One attempt to utilize the “best of both worlds” theory was a single-shot percussion pistol with a large knife blade attached. Patented by its inventor, George Elgin, and manufactured from 1837 to 1838, the Elgin Cutlass pistol, sometimes called the Bowie Knife pistol, was likely inspired by James’s famous fighting knife. Although only a few hundred were ever made—including 150 under contract to the U.S. Navy—this unusual pistol-and-knife combination is worthy of mention here since a few undeniably made their way west. Their presence was confirmed in a St. Louis, Missouri, advertisement in the December 3, 1838, Republican that reads: “Life Guards—Just rec’d two dozen of Elgin Patent bowie knives with pistol attached which will shoot and cut at the same time. For sale by L. Deaver.”

For those heading to the gold fields of California, the January 25, 1849, edition of the Democratic Telegraph and Texas Register proclaimed the bowie as among the necessary items for a wagon trek across the plains, in an article taken from Edwin Bryant’s popular book published the year before: “Every man should be provided with a good rifle, and, if convenient, with a pair of pistols, five pounds of powder and ten pounds of lead…[and] a hunter’s or a bowie-knife.”

This was certainly good advice, since California’s wicked Barbary Coast and hastily created towns in the Mother Lode boasted more than their fair share of lawlessness and raucous behavior, where the bowie and pistol were often judge and jury. In his 1900 memoir of the gold rush, Life of a Pioneer, argonaut James Brown recalled witnessing several high stakes card games in 1850: “Sometimes thousands of dollars would change hands in a few moments…when the strong, with revolver and bowie knife, were law, when gamblers and blacklegs ran many of the towns in California.”

Evolution of the “Iron Mistress”

Regardless of who actually made the first bowie knife, by the early 1830s, James’s “Iron Mistress” existed as a distinct blade type, with great numbers produced with and without the famed clipped point. Possibly, both James and brother Rezin were the foremost proponents of the blade. Early on, they gifted a number of their knives to friends and dignitaries, while working on improvements and design changes.

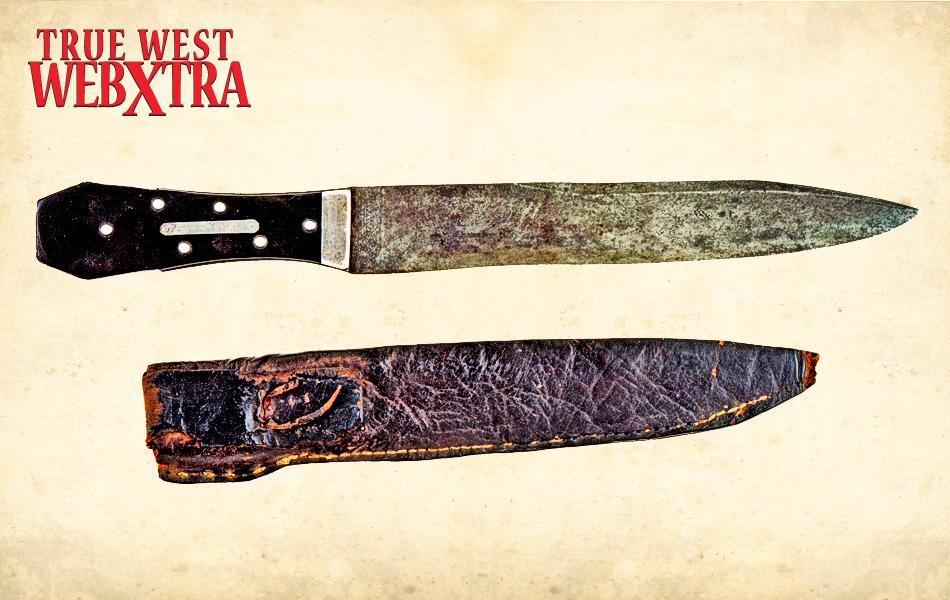

At first, these so-called bowies were hand forged by local blacksmiths supposedly copying the original. These were large knives, from around nine to 15 inches or more in length, with heavy blades that ranged from around one to two inches or more in width. Though ruggedly constructed, they lacked the fine finish of later mass-produced bowies. Further, they were fitted with a simple cross-type guard, often with S-curved quillons or with an iron or brass plate, to keep an opponent’s blade from sliding onto the hand of the wielder. Sometimes a fighting notch would be added to the choil, to catch the blade of an opponent. (Some researchers contend the notch has a more mundane role, of assisting in sharpening the blade.) Grips were usually wood, bone or stag.

One early feature of these American blacksmith-forged bowies was a hardened brass strip along the back of the blade designed to catch the edge of an adversary’s knife during a parry, thus preventing his blade from sliding up past the guard and injuring the hand. While varying in subtle differences, such as blade shape and size, these knives were produced throughout the frontier until after the Civil War.

Knife makers of Sheffield, in Yorkshire region of England, who had been conducting business in America as far back as our colonial period, almost immediately recognized the popularization of the bowie knife in the U.S. and were quick to produce bowies as early as the 1830s. This entry of the British cutlers brought about a secondary and much more ornate breed of bowies. While many of these import blades carried the classic lines of the large-bladed, clip-point American bowies, other styles were introduced, such as the spear point, with blades ranging from six to 15 inches or more in length. Bowies later evolved from a false edge on the clipped point with a sharp cutting border, as found on the early American knives, to a vestigial beveled clip with a dulled edge—although some knives still included the sharpened clipped point.

Other variations, too, were incorporated into these newer bowies. They sported fancier hilts fashioned with German silver, brass, coin and sterling silver mountings, and fitted with one- and two-piece grips made from exotic materials such as horn, ebony, ivory, Mother of Pearl, tortoise shell and German silver. Decorated blades became de rigueur, featuring stamped or etched motifs, animals, patriotic emblems and mottos—some designs were even accented in richly blued or gilt finishes. Fanciful slogans featured on some of these knives included “California Knife,” “Self Defender,” “I’m a Real Ripper,” “Hunter’s Companion,” “I Can Dig Gold from Quartz,” “Texas Ranger” and “Genuine Arkansas Toothpick.”

From Obscurity to Classic

By the mid-1870s the earlier success of percussion revolvers and the decade-old self contained, metallic cartridge repeating firearms relegated the fighting bowie to semi-obscurity. Nonetheless, with frontiersmen still in need of a serviceable blade, the bowie remained an indispensable tool, although it was gradually replaced by smaller versions that were often fitted with synthetic handle materials of celluloid, simulated bone and ivory, hard rubber and thermoplastic.

The practice of carrying a revolver—even a percussion model, which remained popular throughout the 1870s, until that ignition system became gradually obsolete—did not immediately spell the end for the bowie. Despite the effectiveness of cartridge revolvers, many still considered a hefty bowie as their primary defensive weapon or utility tool. None other than famed lawman Wyatt Earp revealed in a 1920 interview by his biographer Stuart Lake, while discussing Kansas City on the Missouri/Kansas border in the early 1870s, “Bowie knives were worn largely for utility’s sake in a belt sheath back of the hip; when I came on the scene, their popularity for purposes of offense was on the wane, although I have seen old timers who carried them slung about their necks and who preferred them above all other weapons in the settlement of purely personal quarrels.”

Bowies continued to see usage by outdoorsmen such as buffalo hunters, scouts, soldiers, Indians, lawmen and others who found a big knife handy for defense as well as utilitarian purposes up into the early 1880s. Regardless, by the end of that era, the popularity of the bowie knife faded. Although far fewer than in the mid-19th century, cutlers continued to make bowie knives, both domestically and in other countries, despite stiff duties imposed on imported blades (and any other import item) by the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890. The famed British bowies, along with those from other countries, continued to enter the United States, albeit with the proper country designation, stamped or otherwise marked on the blade, as required by the legislation. Bowies found today with no such markings are quite likely to have been manufactured prior to 1891 when the act went into effect.

More than a half century after the bowie’s decline in popularity, the knife enjoyed resurgence in the 1940s, as a personal-defense weapon and field utility tool by American G.I.s slugging it out in the jungles of the Pacific during WWII. Because of its favor with these island-hopping warriors, the U.S. Navy and the Marine Corps eventually issued a bowie-type knife. Interestingly, the issue of bowie-style knives was not new, as, through the years, the U.S. military had issued a variety of knives for use by our troops—many inspired by the bowie—including blades such as the 1849 Ames Rifleman’s knife, the Model 1880 Army hunting knife, the Model 1887 Hospital Corps knife, the 1900 Krag Bowie and other blades issued up to and including present day.

Shortly after WWII, the Office of the Chief of Ordnance conducted a study of the use of knives and bayonets by American soldiers, finding that the issuance of a knife had not only been a morale builder, but also that the simple blade was most likely to be retained after discarding all other equipment. Further, the study revealed the knife’s effectiveness in numerous incidents in combat areas where the use of an edged weapon not only eliminated enemy soldiers who penetrated our defense lines, but also saved the lives of many a fighting man.

Today, the bowie, whether vintage or new made, is ranked among the most captivating and collectible of edged weapons. Rare or fine examples fetch well into the five- and six-figure price range at auctions and arms collector’s shows. Handsome and authentic replicas are also being turned out by some of today’s finest custom knife makers, as are various versions of bowies commercially produced in limited quantities. Like the Kentucky rifle and the Colt revolver, the bowie knife is truly an American classic.

For further reading, Phil Spangenberger recommends the following works: Firearms, Traps, & Tools of the Mountain Men, by Carl P. Russell (University of New Mexico Press) and The Bowie Knife: Unsheathing an American Legend, by Norm Flayderman (Mowbray Publishing)

Photo Gallery

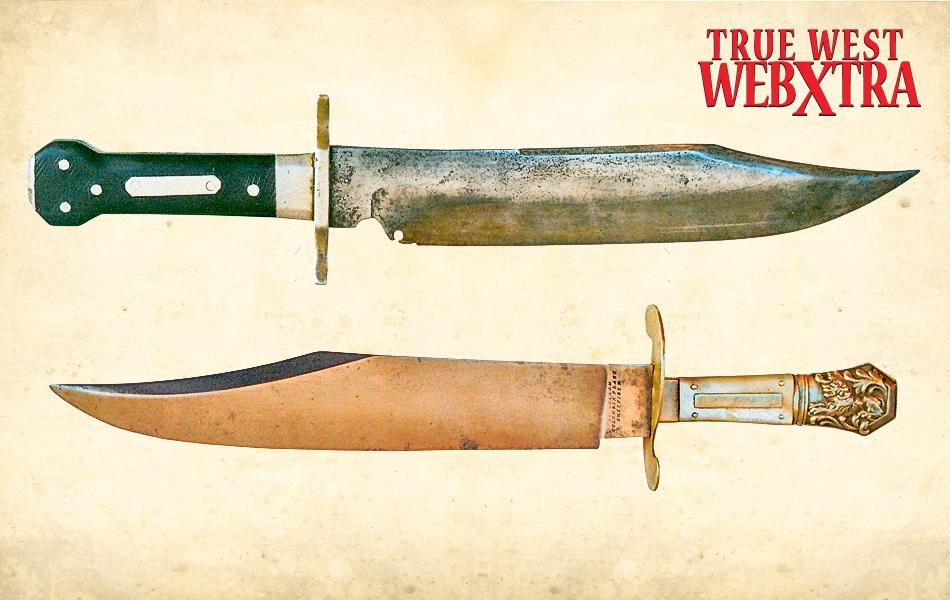

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

The following selection of bowies offers a good idea of the variety, exotic materials used, and the fancy embellishments found on these 19th century fighting and hunting blades. Besides being formidable weapons they are objects d’art.

(top) Unmarked American made, hand forged (c. 1830s), 11 5/8-inch blade, dogbone-shaped ebony handle, German silver mountings, fighting notch in choil.

(bottom) Tillitson, Columbia Place, Sheffield, England (circa 1850), 10 1/8-inch blade, Mother of Pearl scales with German silver pommel with lion.

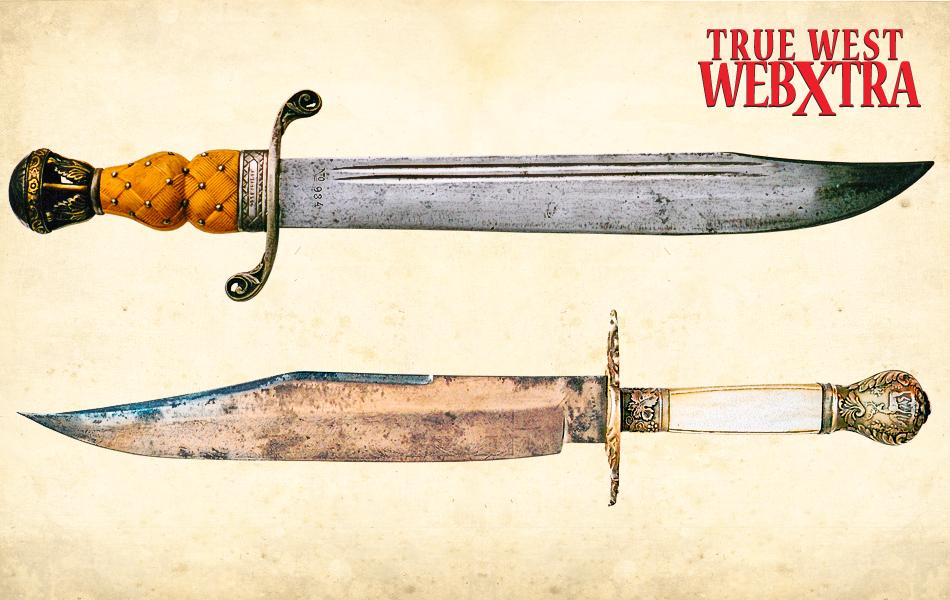

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

(top) Weyersburg Kirschbaum & CO., Solingen, Germany (c. 1880s), 13-inch blade, celluloid handle, German silver and silver-plated brass furniture.

(bottom) John Walters & Co., Globe Works, Sheffield, England (circa 1849), “CALIFORNIA KNIFE” etched 10¾ inch blade, Mother of Pearl scales.

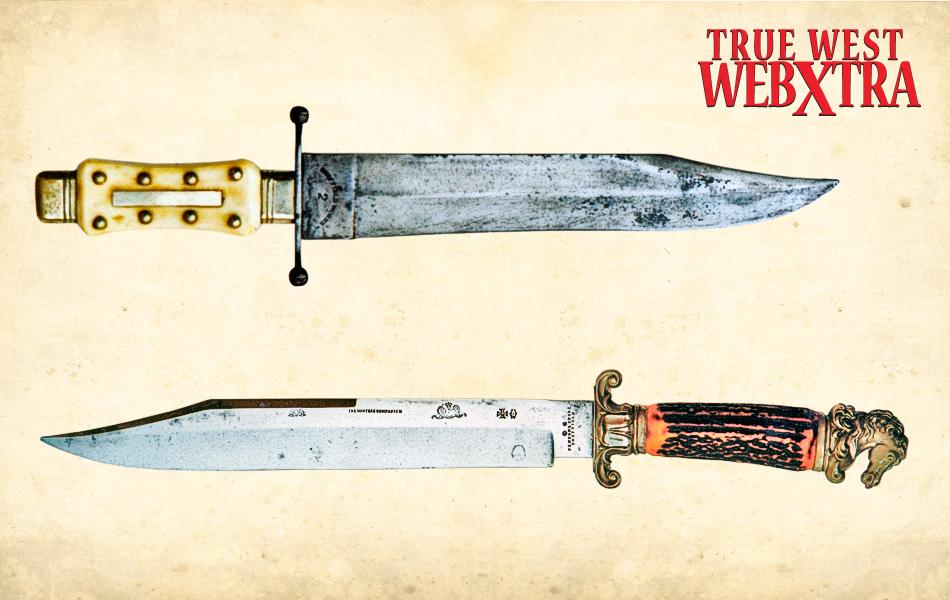

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

(top) English & Hubers, Philadelphia, PA (c. 1834-37), 10-inch blade, one-piece ivory handle mounted in German silver, iron crossguard.

(bottom) Fenton & Shore, Sheffield, England (c.1850), 13-inch blade, one-piece stag handle with German silver horse head.

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Historic Arkansas Museum –

– Courtesy Joseph Musso Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck Jr. Collection –

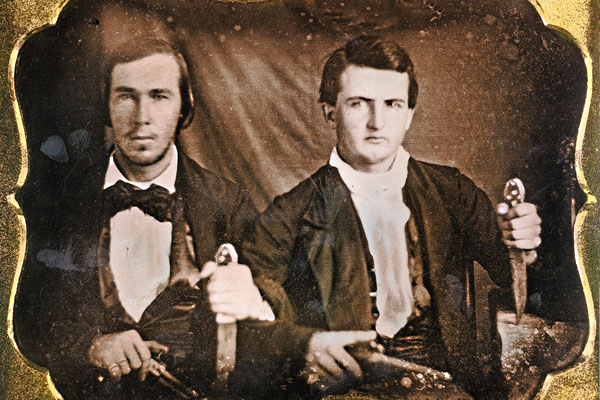

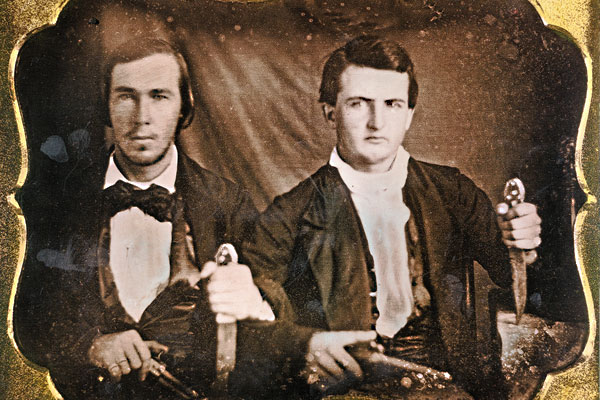

– True West Archives –