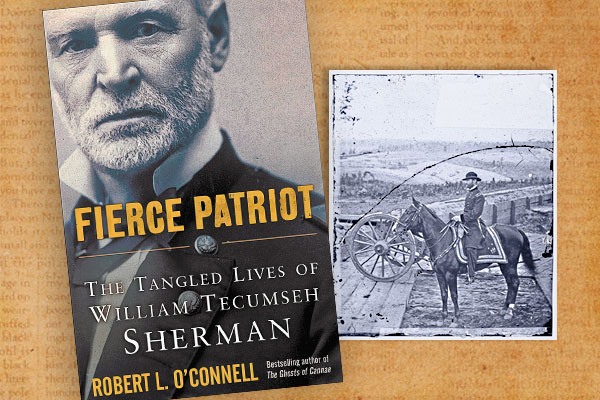

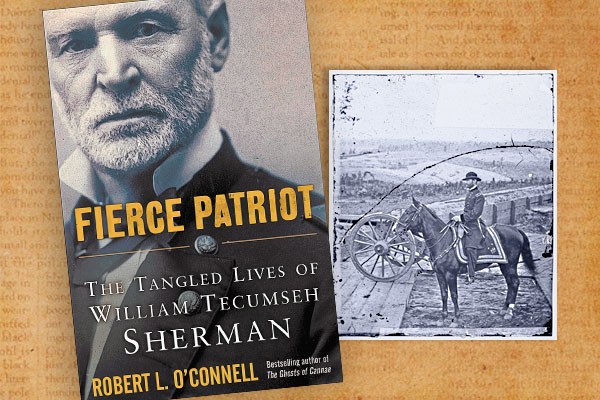

Robert O’Connell’s brilliant biography, Fierce Patriot: The Tangled Lives of William Tecumseh Sherman (Random House, $28), is a well-researched study of one of America’s most iconic and eternally recognized military leaders. O’Connell’s study of the Yankee-born West Point graduate revels—and reveals—the lighter and darker characteristics and personality traits of possibly the most influential post-Revolutionary American general in history.

Robert O’Connell’s brilliant biography, Fierce Patriot: The Tangled Lives of William Tecumseh Sherman (Random House, $28), is a well-researched study of one of America’s most iconic and eternally recognized military leaders. O’Connell’s study of the Yankee-born West Point graduate revels—and reveals—the lighter and darker characteristics and personality traits of possibly the most influential post-Revolutionary American general in history.

O’Connell, a renowned military historian and a Naval Postgraduate Intelligence Center visiting professor, has created an extremely accessible—and insightful—study of Sherman, whose legendary Civil War career gilds our memory of him as the liberator of slaves and apocalyptic destroyer of the South. O’Connell weaves a dynamic portrait of Sherman, who had a transcendent career that spanned the majority of the 19th century and the rise of the American Empire. His five years astride, with his terrible swift sword scything through the South, maybe how he is memorialized astride his gilded horse adjacent to New York City’s Central Park, but Sherman’s coast-to-coast military career that shaped America, before and after the War Between the States, is how he should be remembered. As O’Connell states so succinctly, “He played a significant role in defining us—dimensionally, in the nature and spirit of our fighting forces, and our ethos, or at least the celebrity version of it. Historically, he was one of the ingredients for what we became. A continent for the taking brought forth people like Sherman, and they in turn produced us.”

With the simultaneous commemoration of the American Civil War and World War I occurring for the next two years, O’Connell’s biography of Sherman provides us a perspective that is both poignant and reflective of two wars interconnected by the carnage of battle, the killing and maiming of a generation of men, and the absolute terror brought to the citizens whose lives and lands intersected with the horror of war. Interpreters of the Civil War can easily focus the outcome of Sherman’s leadership and actions in terms of his Eastern campaigns, but, with greater delineation, as O’Connell so expertly points out, Sherman’s enormous energy for war did not end with his victory march on Pennsylvania Avenue. Sherman did not lay down his arms in 1865, but redirected his fighting skills, with his well-honed general staff, to the Indian Nations of the American West. His legacy, of winning at all costs, a precursor of modern 20th century warfare (not overlooking his colleague Gen. Phil Sheridan’s advising the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870), must be considered in greater context to the American-Indian Wars from 1865-1890. I am hopeful that O’Connell might return to the complex—and complicated—life of Sherman, or as he likes to call him (as did his soldiers) “Uncle Billy,” and provide a follow up volume that provides an even more insightful and more detailed understanding of Sherman’s post-Civil War career. As O’Connell states so emphatically: “by the time he retired from the U.S. Army in 1884, Sherman had become virtually a human embodiment of Manifest Destiny.”