All across the Pacific Northwest are reminders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06, although no tangible physical evidence remains. There are rivers, schools, universities, a wildlife refuge and other features named for the exploring party including the two captains.

All across the Pacific Northwest are reminders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804-06, although no tangible physical evidence remains. There are rivers, schools, universities, a wildlife refuge and other features named for the exploring party including the two captains.

In Oregon, interest in the pioneering expedition to the western sea came a hundred years after the original journey—in 1905, when Portland hosted the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. That was the first World’s Fair held on the Pacific Coast, and it celebrated the role Lewis and Clark played in extending American territorial claims and the opening of a commercial passage into the far West.

The Journey Begins

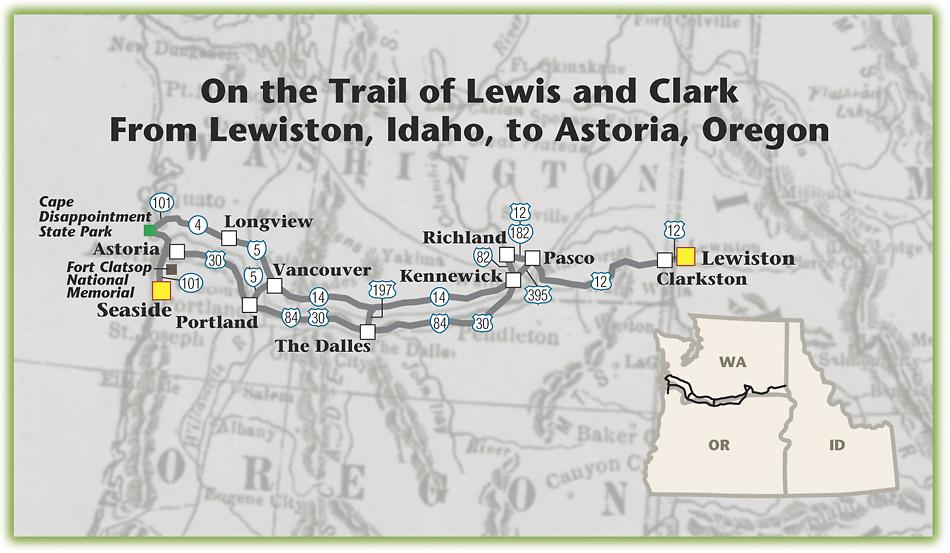

Let’s begin following the Lewis and Clark route in the two cities located across the Snake River from each other that bear their names. The Snake River separates Lewiston (in Idaho) and Clarkston (in Washington). From Lewiston, a jet boat trip up the Snake toward Hells Canyon should not be missed, while in Clarkston, a tour of Chief Timothy State Park with its interpretation of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery expedition is worth the visit.

I’m not much for rivers and boat rides, but the journey on the Snake is exhilarating and shows you the rugged landscape the exploring party traveled. If you go far enough you will get to Dug Bar, the place the Nez Perce Indians with Chief Joseph crossed in 1877 when they left the Wallowa Valley just prior to their flight across the Rockies to Montana in an effort to stay off the reservation at Lapwai, Idaho.

The Nez Perces provided great aid to Lewis and Clark’s expedition, giving them food, rest, and, most of all, information. The expedition force camped with the Nez Perce people on both their east and westbound trips.

Westward Down the Columbia

From Clarkston, continue west on Highway 12 to Tri-Cities—Pasco, Kennewick and Richland, Washington. Lewis and Clark reached the confluence of the Columbia and Snake Rivers here on October 16, 1805. They spent a couple of days meeting with local Indians and recording information about their customs as well as the regional flora and fauna.

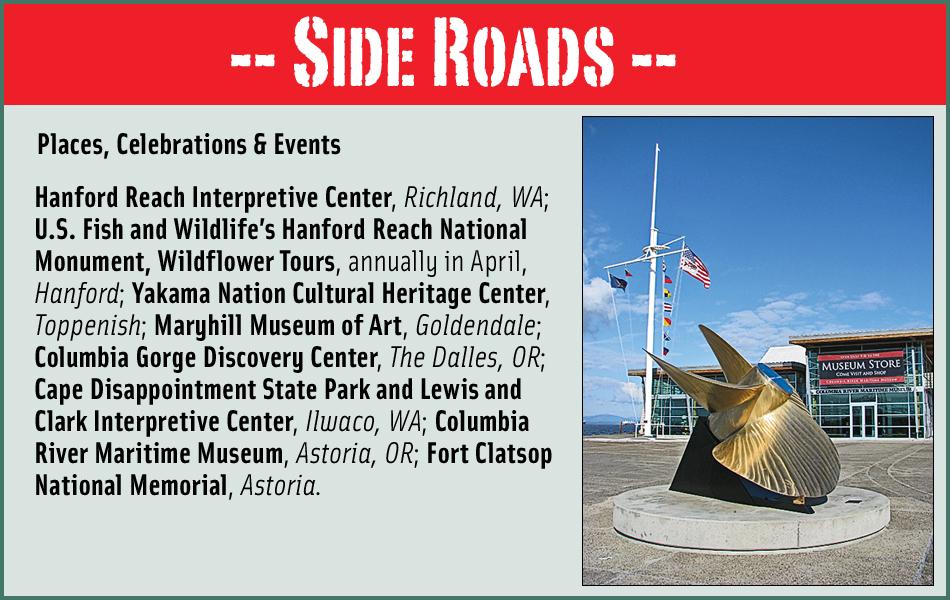

In Pasco, overlooking the confluence of the Snake and Columbia, visit Sacajawea Park, with an interpretive center that has information about the expedition. To learn more about the wildlife and plants of the region, schedule a stop at the Hanford Reach Interpretive Center (slated to open in early July in Richland). The new museum has numerous exhibitions about the geologic forces that formed the region, the massive floods that carved the landscape, and the birds, plants, mammals and other critters that live along the Columbia River.

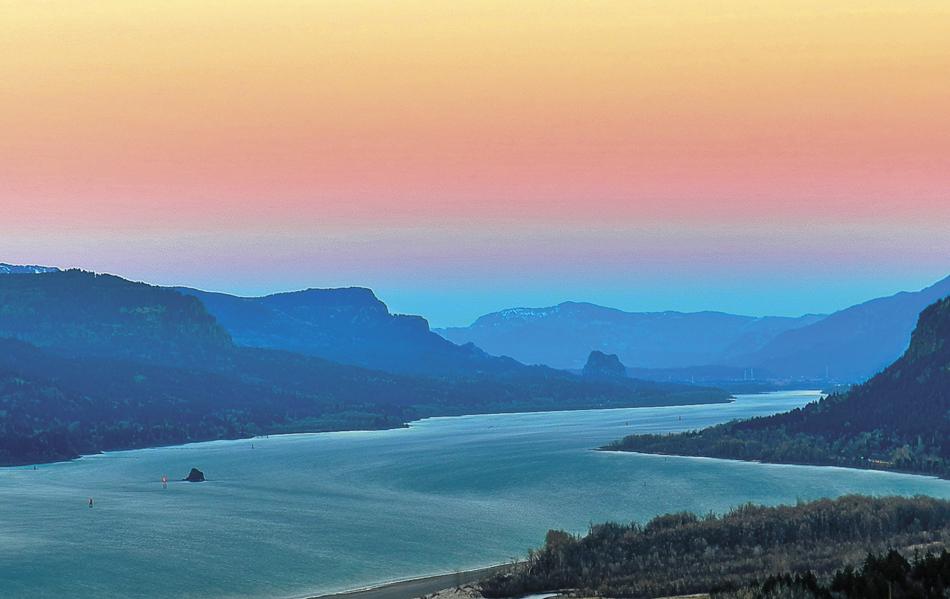

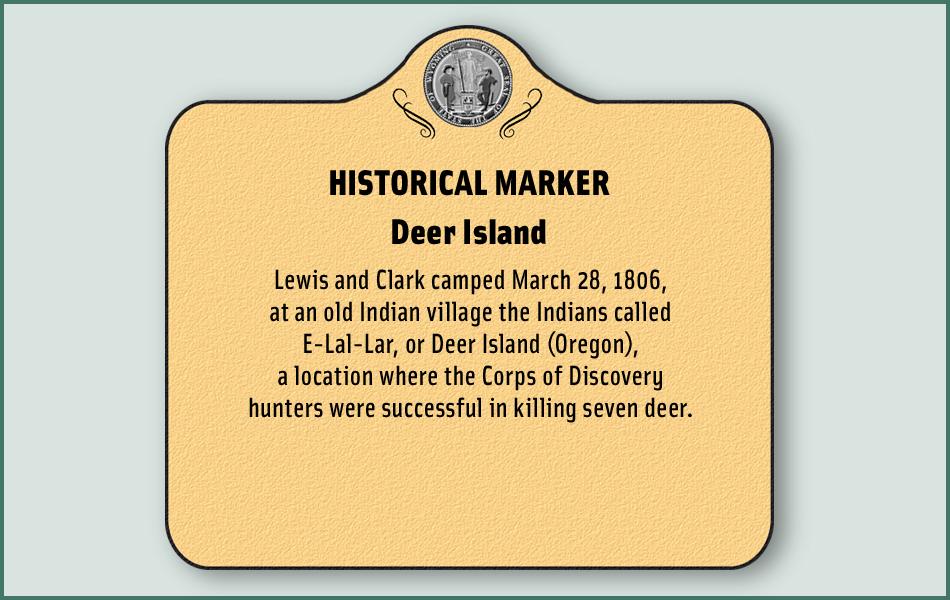

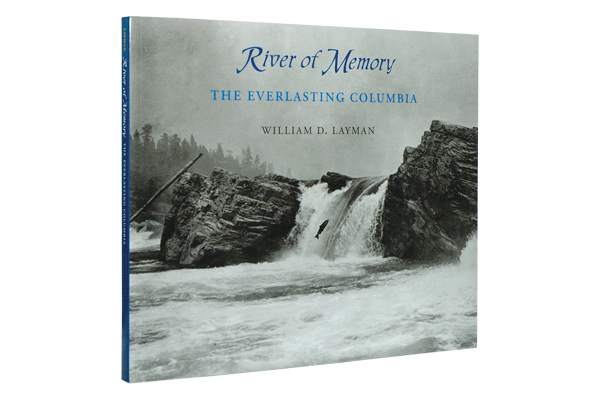

From the Tri-Cities continue south on I-82 and follow the Columbia River west. You can travel either on the Washington side of the river (State Highway 14) or cross into Oregon and take I-84. Either way you will enter the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, and should plan to stop at The Dalles, Oregon. This site had been used as a trading location for native people for generations before Lewis and Clark got here. The Celilo Falls was an important tribal fishing area, and tribal traders from the Pacific Northwest gathered to exchange goods with traders who came from as far away as Mandan Village (where Lewis and Clark over-wintered in 1804-05) and even present-day southern Wyoming and New Mexico.

This was a pivotal point for Lewis and Clark, as well as later Oregon Trail travelers. Today, the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center features an exhibit about the gear and goods Lewis and Clark packed on their journey.

One tangible artifact of the expedition is a branding iron Captain Meriwether Lewis carried. While the full story of the branding iron is not known, it may have been made in 1804 at the armory at Harpers Ferry, or perhaps by iron worker and expedition member Private John Shields. The branding iron may have been traded when the expedition was camped near The Dalles. A resident of Hood River, Oregon, found the artifact near Memaloose Island on the north shore of the Columbia River in the 1890s. He gave it to The Oregon Journal (the former Portland afternoon newspaper) publisher Philip L. Jackson, who later donated it to the Oregon Historical Society.

Lewis most likely had used the iron to mark expedition goods such as wooden packing crates, barrels and leather bags. The captain also marked trees as the expedition journeyed west. On June 10, 1805, the party had cached a pirogue on an island located near the mouth of the Marias River in Montana. Captain William Clark wrote in his journal that Lewis “branded several trees.” The tree blazes also served to mark territory as imperial claim markers under the Doctrine of Discovery. This European legal theory held that the first European nation to “discover” a previously unexplored area could colonize it, a practice that played an important role in justifying American claims to the Oregon Country.

You can cross the Columbia at The Dalles, to continue your westward journey, either in Oregon traveling on the interstate or in Washington on the state highway. Both routes give you much the same view as they follow the river. Lewis and Clark were north of the river in this location and I much prefer the Washington highway, although (or perhaps because) it is the slower route.

“Ocian in view! O! the joy.”

Captain William Clark wrote these words in his journal on November 7, 1805, and he must have believed he truly had reached the Pacific Ocean. He actually was at the Columbia River estuary and it would take another two weeks of traveling to make it to the Pacific, a place they had “been so long anxious to see.”

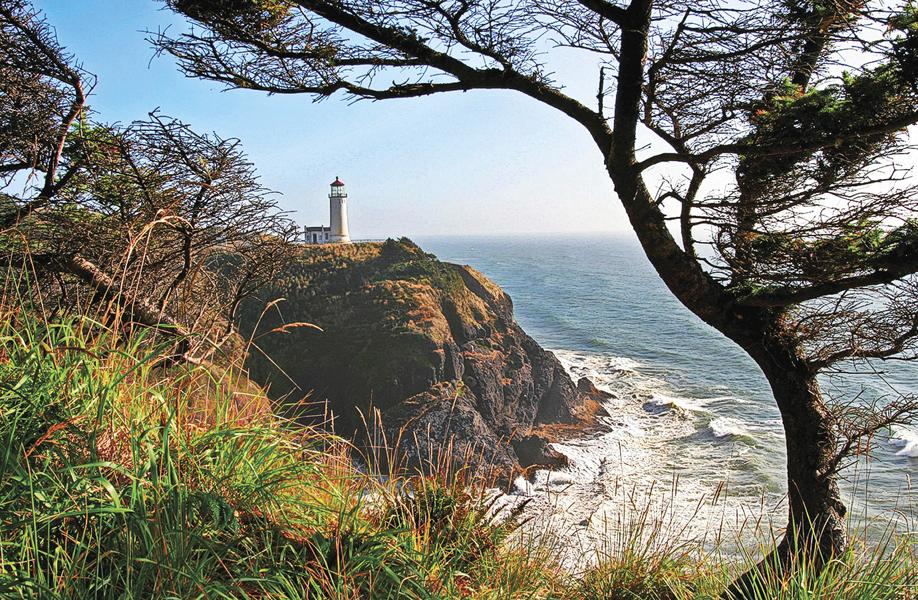

Once at the ocean, at what is now Cape Disappointment State Park south of today’s Long Beach, Washington, the expedition quickly found that the coastal climate was challenging as continual storms swept the area. Within 10 days of arriving on the coast, Lewis and Clark decided to leave their storm-bound camp on the north shore and cross the river, where elk were reported to be plentiful.

Lewis, with a small party, scouted ahead and found a “most eligible” site for winter quarters. On December 10, 1805, the men, now in what would become Oregon, began to build a fort about two miles up the Netul River (now the Lewis and Clark River), not far from the present town of Astoria, Oregon. They had their quarters pretty well complete by Christmas Day, naming it Fort Clatsop, for the local tribe of Indians.

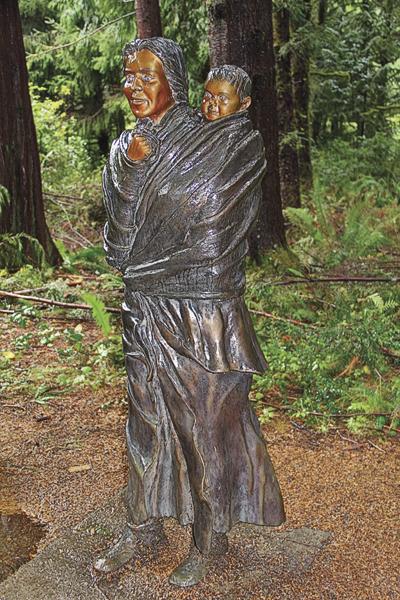

John T. Dizney worked at the Warm Springs Indian Agency in Oregon and in 1903 wrote to an Oregon City novelist, providing details from members of the Warm Springs Tribe about the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Among the oral stories handed down for most of a century was one about the man so black they gave him “the name of the raven’s son.” While these Indians recalled the presence of York, Captain Clark’s slave who accompanied the expedition, they handed down no stories of an Indian woman. Perhaps the presence of the Shoshone woman Sacajawea was less remembered because she did not seem so different to the Warm Springs tribal members.

There is a sculpture of Sacajawea carrying her young son Baptiste Charbonneau on the grounds of Fort Clatsop National Memorial. There is nothing original left of this post, and indeed the National Park Service replica you can visit now is not even the original replica—that one burned down during a reenactment when some hot coals sparked a middle-of-the-night blaze.

Even though it is not authentic, nor the first replica, Fort Clatsop is a great place to visit because you can still get a sense of the conditions the Lewis and Clark Expedition endured while they were here for that three-month winter period in 1805-06. It is in the forest, which always seems to be dripping with rain. In addition to touring the replica fort and small interpretive center, you can hike along trails in the area and attend the interpretive programs that take place most days.

While over-wintering here, the expedition members no doubt rested. They wrote in journals, and some men established a salt-making camp near the ocean (which is often reenacted by modern-day interpreters near Seaside, Oregon). The captains began organizing their scientific information and they traded with local Indians. Then, in early March 1806, they departed the area en route back to St. Louis.

Their expedition to the Pacific Northwest was the harbinger of American exploration, as they would be followed by the mountain men, and later emigrants, who took a different route to the Oregon country, ultimately claiming it for the United States.

Road warrior Candy Moulton hangs her hat near Encampment, Wyoming, when she makes it home on occasion.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Vancouver USA Regional Tourism Office –

– Courtesy of the Long Beach Peninsula Visitors Bureau –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Vancouver USA Regional Tourism Office –

– Courtesy AWACC –

– Photo by Candy Moulton –

– Courtesy The Columbia Gorge Discovery Center and Wasco County Museum –

– Courtesy AWACC –

– Photo by Peg Owens, Courtesy Idaho Tourism –