The Canadian prairies were anything but polite in 1885. In southwestern Alberta, rancher William Cochrane wrote his father: “There is a great deal of uneasiness about the Indians…Riel’s runners are in their camps, and it seems doubtful what they will do…we ought to make every effort to get more protection here from the Government.”

The Canadian prairies were anything but polite in 1885. In southwestern Alberta, rancher William Cochrane wrote his father: “There is a great deal of uneasiness about the Indians…Riel’s runners are in their camps, and it seems doubtful what they will do…we ought to make every effort to get more protection here from the Government.”

On the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers, discontent among the mixed-blood “Métis” society, and those of their Cree and Assiniboine allies, erupted into armed conflict. The intents of Blackfoot nations closer to the Rocky Mountains and the U.S.-Canada border were still in doubt. To newcomers like Cochrane, remote living brought fears.

A rout by the forces of Métis firebrand Louis Riel over the North West Mounted Police at Duck Lake that left 17 combatants dead on March 26, and the declaration of a provisional government, provoked the Canadian establishment to mobilize its militia. News of uprisings at Frog Lake and Battleford by Cree allies stirred the prairies and brought the loyalties of other bands into question.

As the Blackfoot, Blood and Peigan tribes watched their buffalo grounds become a cow pasture, they were confined into blocks called “reserves,” where they were handed out food and told how to live. With cattle herds belonging to ranchers like Cochrane appearing and the Canadian Pacific Railway laying track across the prairies, a way of life was drastically altered, and warriors were tempted into rebellion.

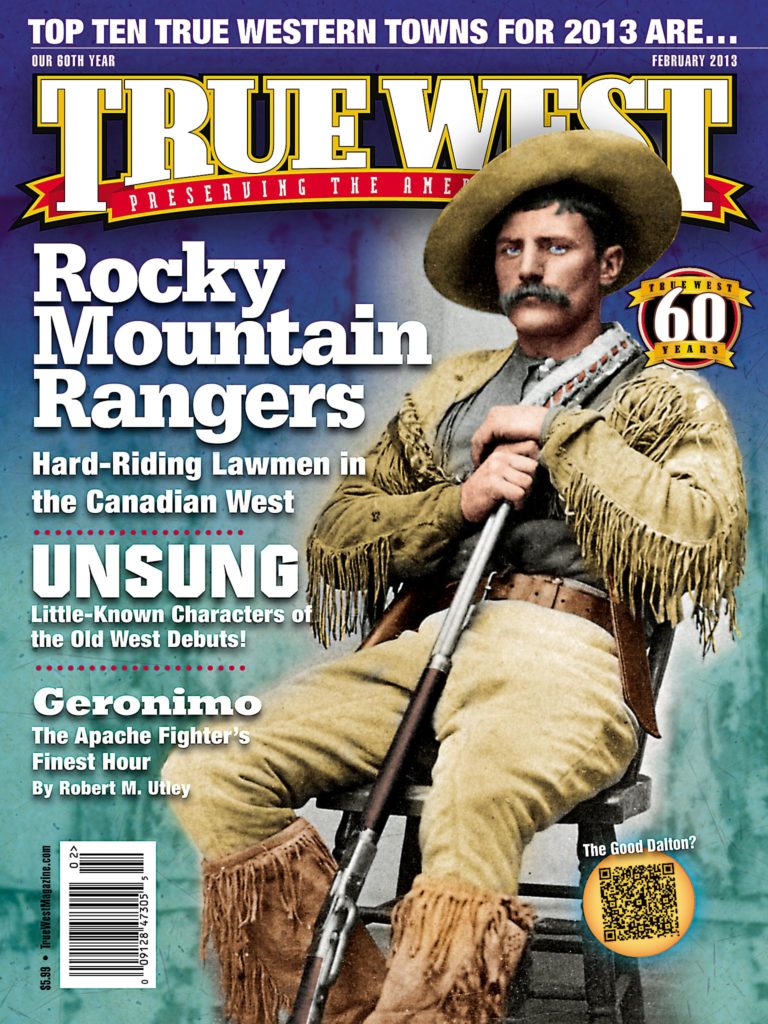

In the confusion and unrest, frontier residents looking to protect their settlements volunteered for service in the irregular militia—the Rocky Mountain Rangers. Commanded by John Stewart, a rancher-turned-militia officer, the Rocky Mountain Rangers was a microcosm of citizens, stockmen, trappers, politicians and discharged Mounties hammered into an irregular cavalry unit.

Volunteers were needed to guard a 200-mile frontier between the Rocky Mountains and the Cypress Hills, protect cattle herds from thieves and rustlers and keep an eye on the border. Stewart was authorized to recruit Americans, who accounted for a large fraction of local population—robe traders, range riders and bull-team freighters working new homesteads—a rich resource of homegrown talent who knew the prairie, and how to ride and shoot.

Stewart had no qualms about drafting friends, business partners and neighbors into his officer’s corps. As commander, Stewart looked to his circle of comrades in business and military organizations; he felt fortunate that a remote area could produce good staff material. Volunteer recruitment yielded 100 men for the new regiment, comprised of rank-and-file working hands from local ranches.

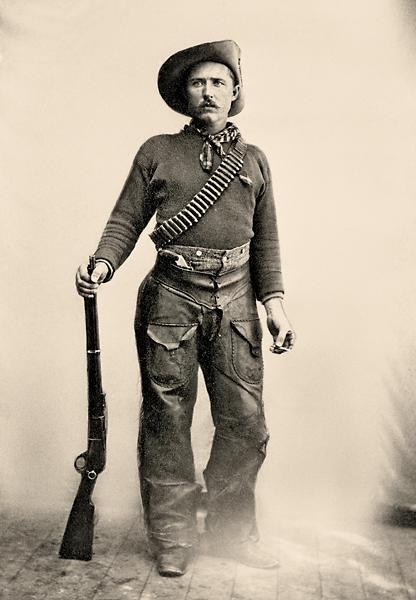

When North West Mounted Police artillerymen were ordered north to the scene of the Cree uprising in Frog Lake in April 1885, the Rocky Mountain Rangers reinforced the diminished Macleod garrison. Volunteers were expected to provide horses, tack and firearms, but as uniformity and quality of weaponry were problematic, Stewart distributed fifty Model 1876 .45-75 Winchester rifles. With personal sidearms, the Rangers were “armed to the teeth, should occasion require.”

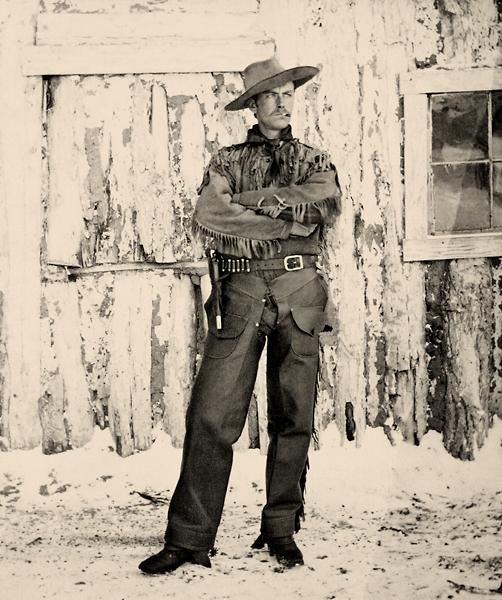

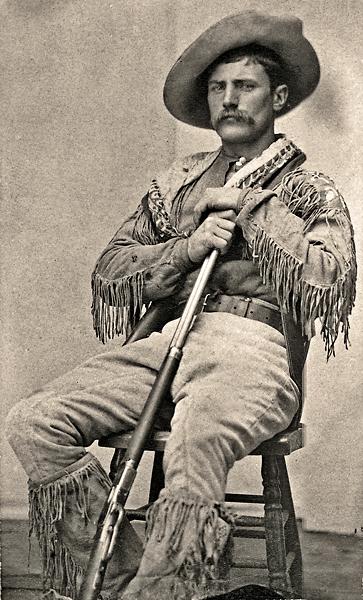

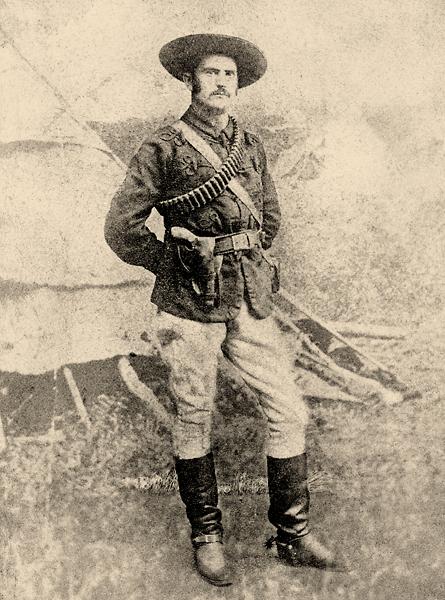

Armed with these sidearms, the Rangers had no identifiable uniform, just functional work clothing: “a sombrero, or a broad-brimmed felt hat with wide leather band, coat of Montana broadcloth or brown duck (canvas) lined with flannel, a shirt of buckskin, breeches of the same or Bedford cord, a cartridge belt attached to which is a large sheath knife, and the indispensable leather chaps. Top boots with huge Mexican spurs completed the equipment.”

Ex-Mounties accessorized with yellow-striped breeches. Rangers were encouraged to pin the left side of the wide brim of their felt slouch hat up the crown. A possibility exists that some Rangers may have worn a hatband of red material signifying them as Dominion militia.

These men did not take basic training seriously—humorous tales were told of troopers breaking out of formation, promising to catch up later. One officer ordered his charges to “halt, dismount, and have a drink.” But hard drilling was unnecessary—the Rangers could ride and shoot, had the resolve to fight and knew the vast open lands they patrolled.

After assembly, the Rangers mobilized. John Higinbotham described their departure: “Their tanned faces almost hidden beneath the brims of huge Spanish sombreros, strapped on for grim death…. Cross belts pregnant with cartridges, a six-shooter, sheath knife, a Winchester slung across the pommel of the saddle and a coiled lariat….”

Divided into three troops, one company remained behind to guard the hilly ranch country, triangulating between Fort Macleod, Pincher Creek and High River, and the nearby reserves. Two companies marched east to Medicine Hat to guard railroad bridges, construction camps and the boundary country. As battles raged to the north, the Bloods and Peigans were quiet, and the Blackfoot pledged neutrality. Still, loose stories of marauders abounded.

To augment the numbers, the Rangers sought out more recruits, spurred on by Rattlesnake Jack Robson, the long-haired scout, who “wore a buckskin shirt or coat with two revolvers in his belt.” With headquarters established in Medicine Hat, patrols were sent into the Cypress Hills, strategic hunting grounds of the Métis, with sheltered trails leading to Montana.

Stewart felt that embattled Cree or Métis might regroup in the Hills or escape through the dense jack pines, into American settlements, and posted a $1,000 bounty for the capture of Riel. With the eventual Métis defeat at Batoche, Riel surrendered to government forces, but the Rangers failed to capture Riel’s military general, Gabriel Dumont, a legendary buffalo hunter whose knowledge of the country allowed him to slip across the border.

Stewart’s Rangers held lonely vigil across a vast unguarded border—open territory for horse rustlers believed to be American Assiniboine or Gros Ventre. For reliable intelligence, the Rangers dispatched their best scout, William Jackson, who was fired on by a raiding party. The scout returned fire, and after several volleys, the party galloped away. Jackson reported in and guided the Rangers back to the site of the exchange. Some were skeptical of Jackson’s word, but the scout started a signal fire that was acknowledged with corresponding smoke. The Rangers gave chase, but the quarry escaped.

Routine police work was accomplished by combined Rocky Mountain Ranger and North West Mounted Police patrols, and one such team broke a rustling ring in the Macleod-High River corridor. For the most part, the Rangers delivered dispatches, visited ranches, escorted freight wagons and kept general vigilance. With the defeat of the Cree at Frenchman’s Butte and Loon Lake, and the July 2 surrender of Big Bear at Fort Carlton, the revolt was broken.

With threats past, the Rangers were ordered back to Fort Macleod and disbanded after only three months’ service. For exemplary performance and hardships endured, 114 Rangers were awarded the North West Canada Medal and became eligible for 320 acres of homestead land. These grants encouraged the veterans to become established as pioneer settlers in southern Alberta.

Though seeing little action, the Rocky Mountain Rangers lived up to the expectations of a military unit in a crisis—to maintain peace and order. Through many hours in the saddle, communities and lives were guarded, rumors were quashed, property protected and a conflict prevented from escalation. In their further careers as ranchers, businessmen, townsmen and politicians, the ex-Rangers did much to build the modern southern Alberta. Kootenai Brown even helped to create a National Park–Waterton Lakes (bordering Montana’s Glacier National Park). Whatever the Rangers suffered in lack of battlefield glory, they can be proud that their presence prevented their home from the bloodshed plaguing other fronts of the North West Rebellion.

Gordon E. Tolton, of Coaldale, Alberta, is the author of The Cowboy Cavalry: The Story of the Rocky Mountain Rangers and Prairie Warships: River Navigation in the Northwest Rebellion. He has worked with Fort Whoop-Up and Great Canadian Plains Railway Society, among other historical groups.

Photo Gallery

Courtesy Glenbow Archives NA-4452-7

Courtesy Provincial Archives of Alberta A.19402

True West Archives

Courtesy Glenbow Archives NA-619-3

Courtesy Glenbow Archives NA-670-5

Courtesy Glenbow Archives NA-1724-1

Courtesy Esplanade Archives 0404.0012