On vacation in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a stiff President Calvin Coolidge cut a comical figure, wearing cowboy boots and a 10-gallon hat, as he rode a horse to the base of a mountain.

“We have come here to dedicate a cornerstone laid by the hand of God Almighty!” not-so-Silent Cal told the crowd of about 1,000 people on August 10, 1927. When he finished his remarks, sculptor Gutzon Borglum scaled the mountain summit and drilled six holes—a symbol that work had begun on Mount Rushmore. No report noted whether or not the famously sober president broke into a smile at any point in the proceedings.

The project took more than 14 years to complete, due to weather, inconsistent funding and the difficulty of the job. Via cables attached to hand-cranked winches, dozens of men lowered themselves down the face of the mountain to dynamite, drill and carve the heads of Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln.

The monument was finished on October 31, 1941. In true Halloween trick-or-treat fashion, the monument featured good and bad points. The plus: the sculpture drew thousands of tourists to remote South Dakota, just like the original planners wanted. The minus: neither President Coolidge nor artist Borglum was alive to see it.

Jump ahead to May 2010. Several men and women were lowered down the faces of Mount Rushmore, undertaking a tough task—just like the construction crews of old. Yet they had large camera-like devices, not hand tools or blasting sticks. Theirs was not an effort at creation; the modern project was one of preservation and education.

Welcome to the world of CyArk.

The company dates back to the early 1990s, when engineer Ben Kacyra developed a laser scanning device that created digital blueprints of existing buildings. The earliest scanners were the size of washing machines.

By 2001, the scanners were about as big as a large camera atop a tripod. That year, Kacyra sold the invention to a Swiss company and turned his attention (and the scan technology) toward archaeology. He called the new company CyArk (as in “cyber archive”).

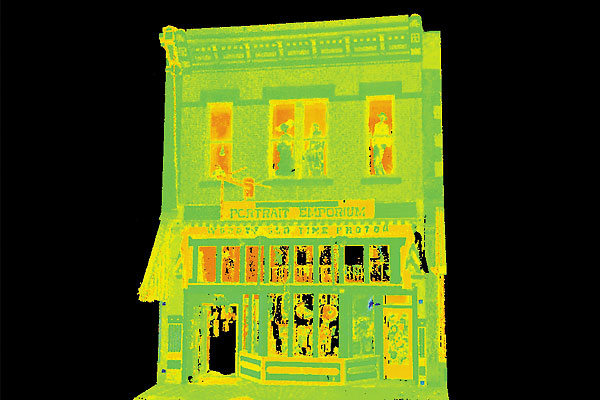

Over the past decade, CyArk has undertaken projects around the globe. What’s more, it has integrated the scans with digital photography to get a three-dimensional model of the subject.

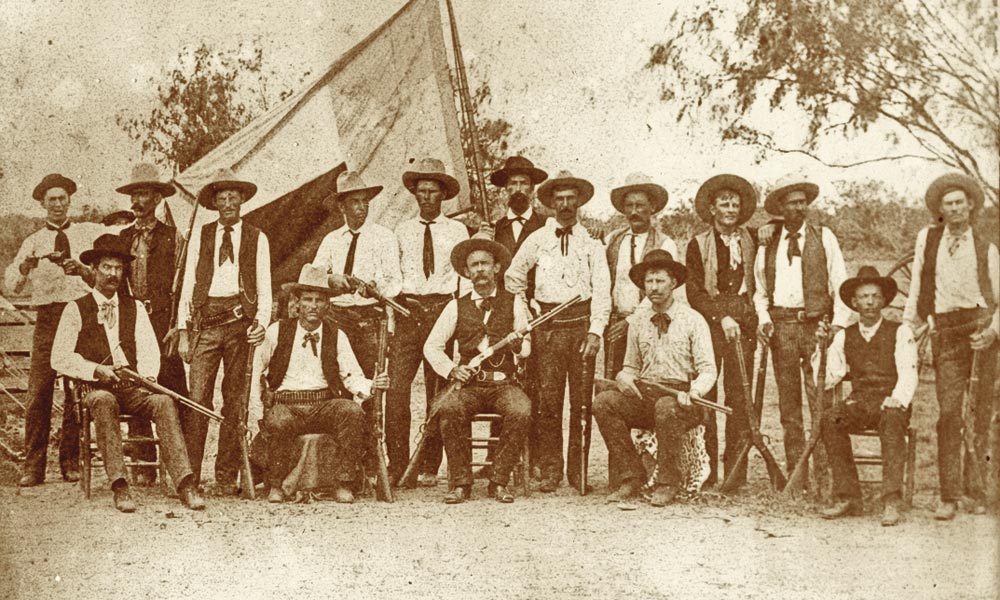

Included among the projects CyArk has worked on are quite a few places dear to us Western enthusiasts: Deadwood in South Dakota, cave dwellings at Mesa Verde in Colorado, Presidio of San Francisco in California and Fort Laramie in Wyoming. The most recent project was Mount Rushmore.

Each project creates an accurate representation of the site as it is today—including color, crack and landscape details, says Elizabeth Lee, CyArk director of projects and development. The three-dimensional models are accurate down to about five millimeters. At Mount Rushmore, the results will show individual carving strokes that can’t be seen by the human eye.

Today’s models can then be compared to ones made, say, five years from now. That will allow preservationists to see how much the rock at Mount Rushmore is moving, and whether freezing ice and thawing water are damaging the monument. Plus, if part or all of the subject were ever destroyed, the model would allow preservationists to accurately re-create it.

The National Park Service is partnering with CyArk on Mount Rushmore (as it did at Fort Laramie and Mesa Verde). Each project has at least one partner, either a private firm, a university, a foundation or a government entity. The partners usually carry the bulk of the cost.

The photos, scans and virtual tours are available to anybody, free of charge, at Archive.Cyark.org. That’s part of another component to the company’s efforts. “We’re going to be working with the Park Service to produce educational materials for K-12 where the 3-D data will be used to create a game for kids,” Lee explains. “It will give them access to areas they wouldn’t normally see, like the top of Lincoln’s head. They’ll see the Hall of Records, which is behind the sculpture, which was originally intended to be accessed by the public but was never completed.”

Lee says the last couple of years has brought about an increase in the demand for such three-dimensional projects as the technology has improved to implement such projects. That good news means crews will now be scanning and photographing even more of our Old West (and other) treasures in the future.

Such undertakings might make even Silent Cal smile.