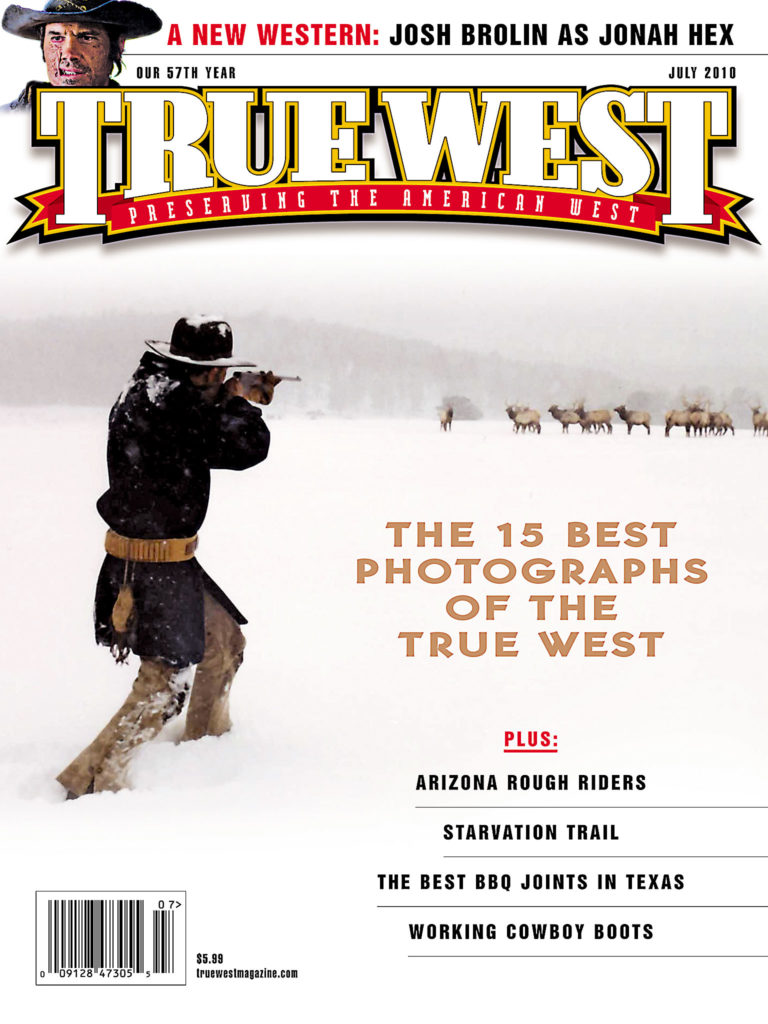

Gold seekers intent on finding the quickest ways to the Colorado gold fields forged the Smoky Hill Trail, but many of them paid a terrible price in their quest as tthey failed to recognize the dangers in crossing the Kansas and Colorado Plains.

Named for the Smoky Hills (a low clay ridge between the Smoky Hill and Republican Rivers in present-day Kansas), the Smoky Hill Trail was used by gold seekers in the late 1850s and as the route of the Butterfield Overland Despatch stage company line begun by David Butterfield in 1862 to link the Missouri River and Colorado mining communities.

Lucian J. Eastin of the Kansas Weekly Herald, on March 1, 1859, set the stage for disaster when he called the Smoky Hill route the best trail to Colorado’s gold mines. News of gold in the Pike’s Peak region had spread throughout the country during the fall of 1858. Missouri River towns, wanting the business associated with the anticipated rush, promoted themselves as the best jumping-off places.

Leavenworth, as Eastin’s article noted, was due east of the gold, although hundreds of miles away. If gold seekers traveled straight to the west they would save days of travel and beat those who opted for the well-established northern road (the Oregon-California Trail) that had been in use since the 1840s. The Smoky Hill route was also shorter than the equally well-established Santa Fe Trail. Eastin pointed out that the Leavenworth route followed a beeline up the Smoky Hill Fork of the Arkansas River.

Eastin didn’t bother to emphasize that the route had “not been explored through its entire length.” His lack of forthright detail, combined with a start too early in the year and just plain old bad luck, led to the most horrific tragedy on any trail to Colorado’s gold fields. But before we get to the tragedy, let’s start at the Missouri River.

Buried Treasure in Kansas City

Today’s Kansas City region drew travelers who came there to “jump off” for the West from points like Independence, Westport, even Leavenworth, where the Smoky Hill Trail had its genesis.

I start my exploration for a Smoky Hill journey at the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. Created from the treasure uncovered by five men who found the Arabia buried under 45 feet of dirt and mud in a farmer’s field, the museum is a snapshot of the goods people would have had available for a journey across the Plains to Colorado in 1859, for the Arabia sank in 1856. That means everything on display in this museum would have been accessible during the period. The array of goods is nothing short of astounding: leather boots and brogans, felt hats, porcelain buttons, jewelry and other personal items; knives, lanterns, chains, buckets and other workday goods; gold flasks, porcelain dishes, pitchers, bowls, table utensils, even toys; and so much more, from Indian trade beads to horse tack.

After a visit to the Arabia museum and a good plate of barbecue at Oklahoma Joe’s BBQ, I am ready to jump off toward the west. I head out of the city on Interstate 70 and take a quick side detour north on Highway 7 to Leavenworth, so I can say I “started” at the genesis of the Smoky Hill Trail. Then I return to I-70, which I’ll follow to the mother lode.

Walking Toward Disaster

Carrying packs and leading a horse also loaded with goods, the Blue brothers—Alexander, Charles and Daniel—trudged across the Kansas Plains on their way to the gold diggings in the Pike’s Peak region in early spring 1859. Leaving their homes in Clyde, Illinois, the brothers had traveled by train to St. Louis and by steamer down the Missouri River to Kansas City. Then they proceeded on foot, purchasing a pony in Lawrence, Kansas, to haul their bedding. In Topeka, they added a couple hundred pounds of flour to the horse’s load. Even so, they were traveling fairly light.

So am I, as I quickly cross eastern Kansas eager to forget about the really poor food I had in one Missouri town; it was billed as an enchilada but was absolutely awful (I should have known not to order Mexican food in this neck of the woods). This unsatisfying meal does not bode well while I am traveling on what will become known as the “Starvation Trail.” I’m hoping I won’t be in the same boat as the Blue brothers by the time I make it to Denver.

As they walked across Kansas, the Blue brothers joined John Gibbs and eight other gold seekers carrying their possessions in backpacks. The expanded party continued to Fort Riley, where the members decided to cut 100 miles off of their trip by following the Smoky Hill route.

The Blue brothers miscalculated this journey on more than one front. First, they believed Gibbs had already traveled the Smoky Hill Trail and knew where it went and what difficulties lay ahead (he had not). Second, they were traveling in March, and they underestimated the potential of blizzards on the Plains.

I head directly to Abilene, a town that did not exist during the early days of the Smoky Hill Trail, but which is sure enough a good place to light and land for a few hours, or overnight. Here you will find one of Wild Bill Hickok’s guns on display at the Heritage Center of Dickinson County. During a tour of the Seelye Mansion, you can learn about patent medicines made by the Seelye Company. For a break, you can have lunch or dinner at the Kirby House Restaurant, which was originally the 1885 home of banker Thomas Kirby. I also recommend dropping in for some tea at Abilene’s Victorian Inn, which also doubles as a bed and breakfast. While in Abilene, you should be sure to catch a ride on the Abilene & Smoky Valley Railroad’s steam engine.

Last Bit of Flour at the Future BOD

When still hundreds of miles from their destination, Daniel Blue recalled, “Here we consumed the last bit of flour and provisions that we had with us.”

Not me, full of good food found in Abilene, I turn the Subaru to the west, again on I-70 to Hays. Hickok was here, as was George Armstrong Custer, and Fort Hays offers information about both of those Western icons. For a change of pace, you may want to play a round of golf at a truly historic course, where the fort’s magazine once served as the clubhouse. But I’m not a golfer, so I instead spend my time exploring the museum.

Established in 1865 to protect Butterfield Overland Despatch (BOD) coaches and travelers along the Smoky Hill Trail and first called Fort Fletcher, the fort closed just six months later when the trail was no longer in use. But it was reactivated in the fall of 1866 to help protect rail workers building the Union Pacific Railway as it extended to Denver, Colorado. At that time the post moved 15 miles west to its current location and was renamed Fort Hays, soon becoming a major supply depot for other forts. Among the frontier army troops stationed at Fort Hays were the 9th and 10th Cavalry’s “Buffalo Soldiers,” the 5th Infantry and the 7th Cavalry, bringing to the area men such as Gen. Philip Sheridan, Gen. Nelson Miles, Maj. Marcus Reno and Gen. George Armstrong Custer.

At the museum you will see two wood frame officers’ homes, a stone guardhouse and a stone blockhouse. The museum hosts a free Independence Day picnic, during which a band concert is held on the museum grounds in conjunction with the city’s fireworks show. Other special events at the fort include “Graveside Conversations,” held the Saturday before Halloween that includes a tour of the Fort Hays cemetery, and “Christmas Past,” a December event highlighting the Victorian buildings.

From Hays I continue west on I-70 to Oakley, where I leave the interstate and head west and slightly south on U.S. 40 through Sharon Springs to Wallace.

When the BOD operated across Kansas in 1865, stations along the route were frequently the target of Indian attacks. To protect the Pond Creek Stage Station, the military established Camp Pond Creek at a site just west of the present-day town of Wallace. The BOD sold out the following year, and the camp moved east to a location beside the Smoky Hill River. At that time it was renamed Fort Wallace. It became an important frontier outpost during the later conflicts between the frontier military and the tribes in the region. A museum operates at the site, and it includes the original Pond Creek Station.

Continuing west I head to Cheyenne Wells, Colorado, for a side trip. I stop in at two museums operated by the Eastern Colorado Historical Society: one dedicated to the telephone, and the other, to the county jail that held inmates starting in 1894.

Last Hope on Starvation Trail

Leaving Cheyenne Wells, I stay on U.S. 40 through Kit Carson and then follow that road back to the northwest where I rejoin I-70 at Limon.

This is wide open country, spectacular to my mind for the fact that it appears much as it might have when the Blue brothers made their fateful crossing. Their lack of knowledge about distance and weather conditions placed them into a horrendous situation. They had few resources and ate bitter grass, an occasional rabbit and a dog that had followed them; they tried but failed to kill a wild horse. Their hopes soared when Daniel saw the snowy peaks of the Rocky Mountains, exclaiming, “The Peak! the peak! I see it afar off there in the westward! Take courage, boys, and let us go on.”

But their meager sustenance took its toll, and Alexander Blue died. Then, unbelievable as it may be, the “uncontrolable [sic] and maddening cravings of hunger, impelled Charles and I to devour a part of our own brother’s corpse!”

Fearing they would still be unable to find food, they then took a part of their brother’s body with them to eat, living on the human flesh, prickly pear and tree bark; it was not enough, and Charles also died.

Daniel once again resorted to cannibalism, going so far as to crack open Charles’s skull and eat the brains, before he gave in to the weariness of the journey. There on Bijou Creek, in eastern Colorado, Daniel Blue would have died, and his horrific story with him, had it not been for an Arapaho Indian who found him lying on the prairie. The Indian carried Daniel Blue to his lodge, where his wife prepared antelope blood and raw antelope liver, saving Blue’s life.

On May 4, 1859, two months after he’d struck out in jaunty step with his brothers to head to the gold fields, Daniel Blue was deposited on the doorstep of the recently built Station 25 of the Leavenworth & Pike’s Peak Express Company on Bijou Creek’s east fork (near present-day Agate).

Blue’s story and similar tales from other men who had followed the Smoky Hill route caused miners to quickly dub the route the Starvation Trail. When Daniel finally reached Denver, he wrote of his experiences but gave up his dream of finding riches in the Colorado gold fields.

As for me, I am ready to explore Denver by visiting the Colorado History Museum and the Colorado Railroad Museum. But, to be honest, all this writing about a trail where people literally starved, just makes me hungry. First, I’m going to find a good meal, perhaps German fare at Café Berlin. Or maybe I’ll just head over to the Brown Palace, Denver’s wonderful 1892 hotel, and eat at Ship Tavern. Or perhaps I should wander down to Osage Street for a steak at Buckhorn Exchange….