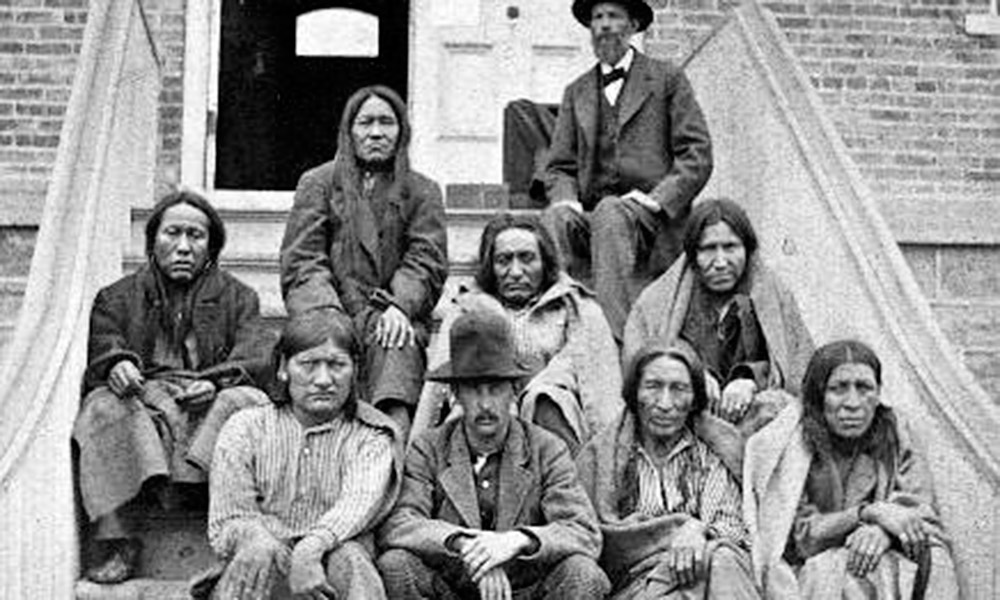

Five months to the day after the Little Bighorn Battle commenced and ultimately resulted in the defeat of Custer and his 7th Cavalry, soldiers charged the winter encampment of Chief Dull Knife and his Northern Cheyennes.

The 4th Cavalry, under the command of Gen. Ranald S. Mackenzie, chased out the Northern Cheyennes, burning their lodges and destroying all of their belongings.

On May 20, 2009, Sotheby’s New York sold a Cheyenne parfleche for a $95,000 bid. It’s not likely from the Northern Cheyenne. Due to the tragic destruction of Dull Knife’s village on November 25, 1876, most of the Cheyenne parfleches found in collections today originate with the Southern tribe, Gaylord Torrence reports in his seminal work, The American Indian Parfleche. Anyone who knows the heartbreaking history of the Northern Cheyenne can understand why they made so few parfleches to replace those they lost, even after Dull Knife and his people were allowed to resettle in Montana in 1879. The government legally set aside reservation land there for his tribe in 1884, one year after Dull Knife’s body was buried near his birth place, alongside the Rosebud River.

Of all the parfleches sold at this auction, the Cheyenne “suitcase” was the most sought after by collectors. “I was not surprised by the selling price of the Cheyenne parfleche,” says Torrence, who currently serves as the Fred and Virginia Merrill curator of American Indian Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri. “They are superb works of art, and they are important objects in terms of their history and provenance.”

Art created by the Cheyennes were strictly maintained by a guild of female artists, which meant that the motifs forming their designs were produced consistently. The exceptional quality of their art is apparent in this auction sale: the brown-black outlining is enhanced by small black triangles placed throughout the design, providing a sense of rhythmic movements. That rhythm continues to be felt with the curving primary triangles in transparent green and red.

As Torrence states in his book, the composition of a Cheyenne parfleche exhibits “nearly equal amounts of painted and unpainted surface area….” You can see how this parfleche is divided vertically into four sections. Torrence discusses this format, stating it is a variation of the Arapaho design. In these four sections, you can see “three triangular shapes arranged along each side of the central band and along the outer vertical borders. The two remaining bands located midway between these are usually elaborated into wide lines composed of two colors that flair as they join the borders at their ends.” Those borders consist of two narrow bands of the same color, enclosing another band, which, in this case, has corners filled in the contrasting red.

Besides the sole Cheyenne parfleche, other parfleches that sold at Sotheby’s included those from the Nez Perce, Gros Ventre, Crow and Lakota Sioux tribes. Parfleches originated, most likely, with the nomadic horse tribes of the Great Plains, and they were made and used by at least 50 tribes by the end of the 19th century. They likely evolved from flat, undecorated rawhide bags into the beautiful painted envelopes found in collections today. The majority of those date to after 1880, states Torrence in his book, with parfleches created prior to 1850 being extremely rare. These parfleches likely stored clothing and weapons, as those that stored food broke down more easily and were usually recycled into other objects, such as moccasin soles, horse equipment, knife cases and drums.

Of the envelopes sold at auction, only the Nez Perce parfleche exhibits fringe. Torrence says that we know the Blackfeet used shorter side fringes on parfleches for medicine objects, but we don’t know if that was true with the Plateau Indians like the Nez Perce. Torrence is unaware of a Plateau fringed parfleche being found with its contents intact, which would identify the utility of the parfleche.

“I think visually the fringe is beautiful, and I think certainly it adds a little weight. When I think of a flat case like that hanging from the pommel, the fringe may have helped anchor it, with the motion of the horse,” he says.

The top sale that day hammered in at $220,000 for a Polychromed Wood Sun Mask, believed to have been carved by the well-known Charlie James and found among the Kwakwaka’wakw of northern Vancouver Island. The total auction sale was about $2.1 million.