“This is the best place on the planet. If you don’t come back, there’s something wrong with you.”

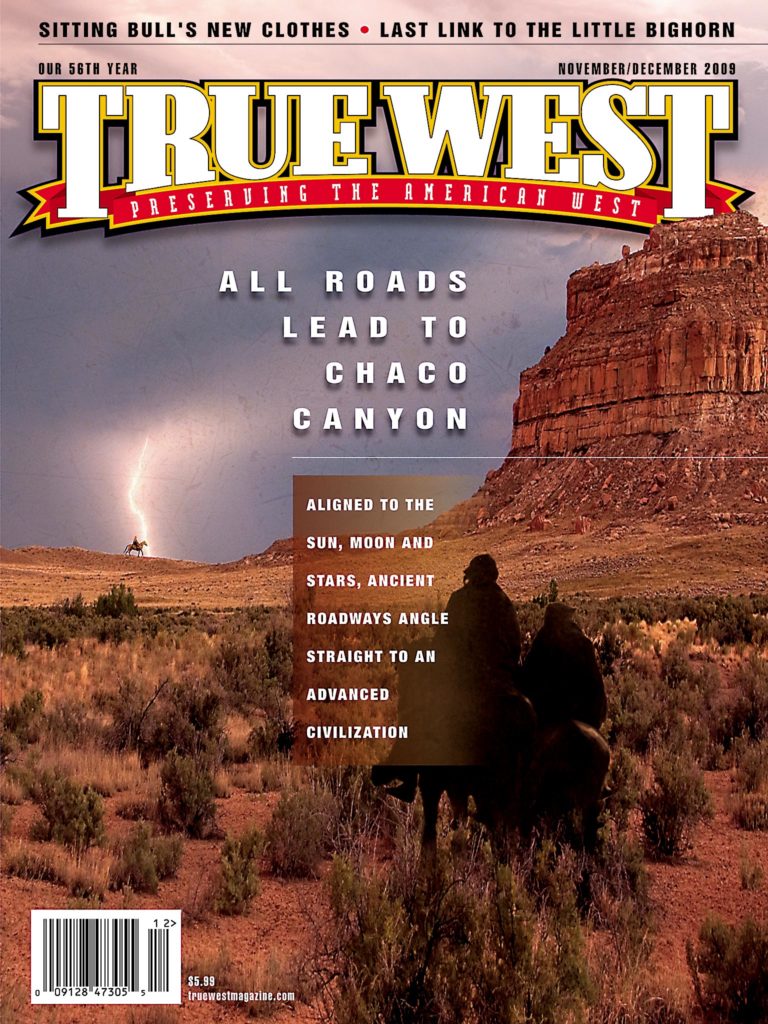

These words spoken by G.B. Cornucopia, a 20-year veteran U.S. Park Ranger, echo in my head as I gaze down into New Mexico’s Chaco Canyon. Desert winds tugging at my hat threaten to hurl it over the canyon rim.

One thousand years ago Ancient Puebloans were building an inter-connected community, the sacred heart of which now lies in ruins at the Chaco Canyon floor. The road system that connects it to distant outlier pueblos is unique. Nothing like it exists elsewhere in North America. Mapping out the roadways shifted the world’s view of these Southwest American ruins, with UNESCO naming it a World Heritage Site in 1987, elevating Chaco Canyon to the level of Peru’s ancient ruins, Machu Picchu, of France’s Palace of Versailles and of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Who were these people, and what was the significance of these buildings they had left behind? The Four Corners region is more than just a place where a Tony Hillerman mystery unfolds; on the roads to the ruins of Chaco Canyon, archaeologists and observant adventurers continue to uncover the secrets of this advanced civilization.

Chacoan Culture

Dubbed “Anasazi” by archaeologist A.V. Kidder in 1936, the Chaco people today are referred to as Ancestral Puebloans. Modern Pueblo tribes do not appreciate the slur of the Navajo word Anasazi, which means “ancient enemy.” Richard Wetherill first applied this term to these people when he “discovered” Colorado’s Mesa Verde ruins after collecting stray cattle in December 1888. The Navajo homeland Dinetah is northeast of Chaco Canyon, and the Navajo actually sheltered the Ancestral Puebloans when the Spanish re-conquered the region in 1692. The tribes inter-married and had other cultural interactions, so it is not likely that Kidder intended the slur when he adopted Wetherill’s term.

The Ancestral Puebloans built 13 sandstone block, multi-storied Great Houses on the floor of the canyon and the smaller Pueblo Alto complex above the canyon’s north rim. Chaco Canyon flourished from AD 850 to 1250 when drought apparently led the Ancestral Puebloans to abandon the region. They moved away and settled to the west and to the south, becoming part of the modern Pueblo people of the Southwest United States. Pueblo people have oral histories about coming from Chaco Canyon, and, to this day, they make pilgrimages to ancient sites in the Chaco Canyon region.

Ancestral Puebloans made turquoise jewelry, pottery and fabrics, trading them with neighboring and distant communities for a wide variety of goods including exotic items such as seashells, copper bells, parrots and macaws. They extended their culture in all directions from Chaco Canyon to outlier pueblos that mirror Chaco’s architecture such as Lowry, Salmon and the misnamed Aztec Ruins, with the Southwest’s only reconstructed kiva (also called estufa) that visitors can walk through. “We don’t really know what went on here,” Ranger Cornucopia says. “Depending on who you talk to, you get a different opinion.”

Trader Josiah Gregg was the first white man we know of to write about the pueblo ruins of Chaco Canyon in 1832. The Army Corps of Engineers under Lt. James Simpson surveyed the buildings in 1849. Richard Wetherill moved to Chaco in 1896 to begin excavations at Pueblo Bonito. He assisted the Hyde expedition, led by George H. Pepper from the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where many of the artifacts they uncovered are found today. In 1901, Wetherill filed a homestead deed to protect the sites until a national park could be created to preserve them. Five years later, the Federal Antiquities Act of 1906 was passed; that same year, Mesa Verde was declared a national monument, and on March 11, 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt named Chaco Canyon a national monument.

The Road to Ruins

The prehistoric road system unique in all of North America runs more than 400 miles of roads in the San Juan Basin, as documented in the 1970s, and experts believe more will be uncovered in the future. The discovery of these roads made it clear that Chaco Canyon was not a solitary prehistoric site but a part of a San Juan Basin-wide community, with roads connecting it to surrounding outliers.

Charles “Lucky Lindy” Lindbergh played a role in solving the road mystery of Chaco Canyon. He was one of the first to take advantage of the fairly new technology of aerial photography to take photographs of Chaco Canyon. The more than 100 aerial shots he and his wife took in 1929, two years after his historic trans-atlantic flight, would later be analyzed by archaeologist Gordon Vivian. Vivian wanted to see if he could detect the prehistoric roadway that Wetherill’s widow, Marietta, had told him about in 1948. The U.S. Geological Survey took more aerial photographs of the region in the 1960s. Then a happenstance meeting between Gordon’s son Gwinn and geologist Thomas R. Lyons in 1970 brought up the possibility of a roadway system once again.

Lyons got the National Park Service and the University of New Mexico to collaborate on investigating the claim. To confirm the fieldwork they gathered, aerial photographs were again taken of the region in 1973, but this time in color and infrared, and subjected to electronic image enhancement. The 80 miles they had surveyed on land increased to 200 miles of known roadways in these photos.

In 1980, Margaret Obenauf published her University of New Mexico thesis, in which she reported her discovery of 200-plus miles of unmapped roadway, which increased the number of known roads to more than 400 miles. That same year, the federal government added an additional 13,000 acres to the site and declared the monument a national historical park.

Only 100 miles of road are in the Chaco Canyon area. The other 300 miles connect distant outlier pueblos to Chaco Canyon. These roads are not simply paths that became well-worn roads after centuries of use; they were surveyed, engineered and constructed by the Ancestral Puebloans. They laid out the roads in straight lines no matter what obstacles were in the way: if stairs needed to be cut they were cut, if ramps needed to be built they were built. When a turn was required, the turn was unlike a gradual curve that we use with our automobile roads, but rather an abrupt angle, and then the road went straight to its destination.

Many of the roads are 30 feet wide; secondary roads are 15 feet wide. Why such wide roads when the Chaco people did not have carts or other vehicles?

The linear design of the roads, particularly the fact that some of them do not avoid topographical obstacles, and the fact that the roads were overbuilt given the technology of the day, led archaeologists to wonder if the roads reflected more than just a system of passage from one place to another.

Cosmos at Chaco

Ranger G.B. Cornucopia, dubbed “Galactic Buddy,” came to Chaco Canyon 20 years ago because he was intrigued by archaeoastronomy, the study of how ancient people understood the sky. Like the ancient Mayans did in the Yucatan Peninsula, the Ancestral Puebloans who built Chaco Canyon used the sun and the moon to track the movement of the seasons and of time. Scientists are discovering that many of the buildings, windows and niches are aligned with the sun, moon and stars, and that certain shafts of light penetrate specific windows during significant solar and lunar events. “It’s a great place to do astronomy,” Ranger Cornucopia says.

As I listen to the ranger, the desert air—cool and crisp—feels refreshing. The October skies are clear and not a breath of a breeze breaks the stillness. “Chaco Canyon is about as remote as you can get in the U.S.,” Ranger Cornucopia continues. “After awhile, you don’t know what century you’re in.”

He points out the spectacular Fajada Butte, majestically rising from the canyon floor. Near the top of it are petroglyphs containing solar and lunar markings. The astronomical nature of these petroglyphs became apparent during a survey conducted with the Solstice Project in 1984-89 that also revealed the solar and lunar orientations of 11 of the 14 major buildings at Chaco.

Among the petroglyphs on Fajada Butte is one marking the ground plan of Pueblo Bonito. This petroglyph stands out from the others because of its unique semicircular shape, which matches that of the pueblo. It also features a spiral curling above, a marking consistent with other petroglyphs on the Butte that are linked to the sun. “Ultimately this petroglyph may deepen our understanding of the design of Pueblo Bonito,” wrote Solstice Project founder Anna Sofaer in her 1994 essay revealing the find.

I walk to Pueblo Bonito, the largest of the canyon’s Great Houses, with Larry Baker, archaeologist and executive director at Chacoan outlier Salmon Ruins. He explains how a portion of Pueblo Bonito was destroyed by a large sandstone pillar called “Threatening Rock,” which did act on its threat and fell on the ruins in 1941. Of all the Lindbergh photos of the site, it is his shot of Pueblo Bonito that resonates most, with Threatening Rock still towering above the pueblo. The 65 rooms that would collapse under the Rock were last excavated by archaeologist Neil Judd in the 1920s.

Pueblo Bonito

Originally four stories tall, the massive Pueblo Bonito contained more than 600 rooms, two large kivas and 38 smaller ones. “Everything is overbuilt here,” Baker says. “It’s very finished.”

Not only are the roads themselves overbuilt, but other findings at the sites have struck archaeologists as esoteric. Evidence of periodic large-scale breakage of vessels, the dearth of burials and even the 10,000 turquoise beads stringing one niche at the bottom of the circular, roofless kiva at Chetro Ketl serve as evidence that Chaco Canyon was not built for the practicality of people’s lives but rather for ceremonial purposes. If the site served as a ceremonial center, that would explain why the Chacoan roads and many of the buildings were built to align with solstice and lunar observations.

At Pueblo Bonito, I walk from one room to the next having to duck my head beneath the low-linteled entrances (lintels are horizontal blocks that span the space between two supports). To move my hand across a wood door lintel touched by people living a thousand years ago gives me a sense of close contact with the Ancestral Puebloan. The wood ceilings look fresh—not 1,000 years old. Thousands of 60-foot-long logs, some up to three feet in diameter, were hauled by the Ancestral Puebloans a distance of more than 50 miles from the Chuska and San Mateo Mountains to construct their Great Houses.

Pueblo Alto

The roads coming in from the north all converge at the north wall of Pueblo Alto, the highest village at Chaco Canyon. To enter Pueblo Alto, the road narrows to a three-foot wide entrance, which archaeologists today theorize may have ceremonial significance.

On my way to Pueblo Alto, ravens soar on updrafts overhead much as they must have for a thousand years. I pass by a broad stairway cut into the rock. I am reminded of William Henry Jackson’s discovery of these Chacoan stairways in 1877, made while he was producing descriptions and maps of the sites under Ferdinand Hayden’s U.S. Geological Survey.

I finally reach Pueblo Alto, where ruins of two Great Houses still stand and traces of the Great North Road can be seen. “I think this place was built to impress people when they came to visit the Chaco Canyon Great Houses,” Baker says.

Twelve miles north of Pueblo Alto, along the Great North Road, is the Chacoan complex Pierre’s Ruins. At the top of a high, natural pinnacle that stands at these ruins, Robert Powers’ 1976 survey revealed a unique archaeological feature in the Chacoan world, a “housed” kiva that aligned with the center line of the Great North Road. He dubbed the cone-shaped hill El Faro (Lighthouse).

Looking at the hearth today, one can see evidence of countless fires. Smoke from a fire blazing here would have been seen for many miles. Upon Powers’ discovery, Dwight Drager theorized a Chacoan signal or communication system in the San Juan Basin. Adding to this theory the evidence of a trade system and the solar research still being conducted to this day, Chaco Canyon’s roadways seemed to have served communication, commerce and religious purposes for the Ancestral Puebloans.

While I stand at Pueblo Alto, I try to see the 30-foot-wide Great North Road. “The lighting has to be just right to see it,” says Baker, who is also having trouble making anything out.

I imagine the Ancestral Puebloans leaving their outlier pueblos to travel along the road to the Chaco Canyon pueblos. The road running straight, disappearing into the distance, constant smoke in the day, fire in the night to guide them on their path.

I walk back to the canyon rim at Pueblo Alto and stand by a large circular cavity carved in the top of the rock ledge. Did Chacoan guards stand here with a fire, or was it built to trap water for them to drink or for some other purpose? I look up from the rock surface and across the canyon floor to a gap in the south canyon wall called South Gap, where another major Chacoan road brought people to the canyon. Through the gap, the wind swirls into a whirlwind, picking up dust and dancing with it across the landscape—it drives home the timelessness, the remoteness of this place.

The Mystery Continues

I have only scratched the surface of what to see and do in Chaco Canyon. While I travel back to Farmington in a tour van, so many unanswered questions rumble in my head. I, like the many others who visit this special place, feel inspired to seek out the answers that will unravel the mystery of our ancient peoples.

One final riddle of that day is marching down the road toward our speeding vehicle. As the van gets closer I see it is a man playing the bagpipes and dressed in full Scottish regalia—kilt and all. The mournful wail of his pipes penetrate our vehicle as it roars past. Why is he piping into Chaco Canyon at the end of the day? I turn and watch as the piper shrinks to a speck and ultimately disappears from view as we drive on. One more mystery.

I still feel the tug to return to Chaco Canyon. I want to find a solitary spot to sit and just ponder in that timeless place. As G.B. Cornucopia says, “This is the best place on the planet. If you don’t come back, there’s something wrong with you.”

Visit BillMarkley.com for more information on Bill Markley and his writing.