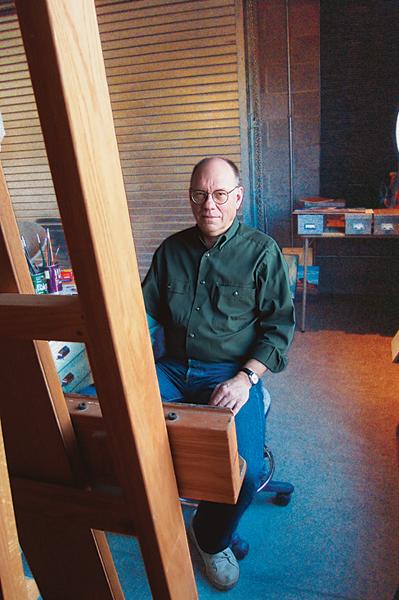

“That line he puts on a canvas to start a painting is never finished,” wrote Donald J. Hagerty when he introduced the world to Phoenix, Arizona-based artist Ed Mell in his 1996 book, Beyond the Visible Terrain.

“That line he puts on a canvas to start a painting is never finished,” wrote Donald J. Hagerty when he introduced the world to Phoenix, Arizona-based artist Ed Mell in his 1996 book, Beyond the Visible Terrain.

But whether it’s an abstract line full of restless energy, or one of realism, depends on the poetry of the moment.

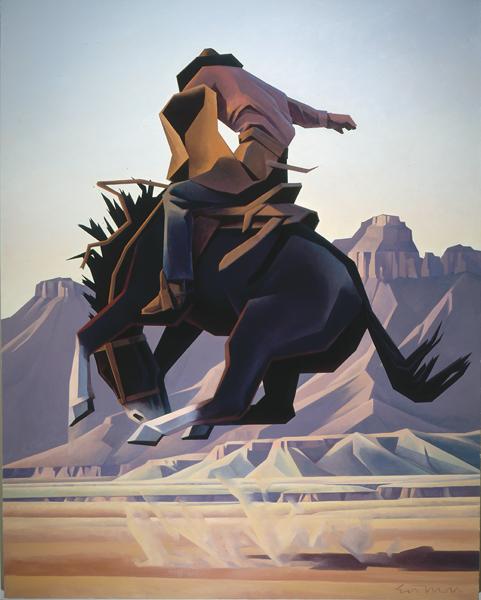

One thing’s for sure. It’s been a while since Mell has painted cartoony illustrations, such as Porky Pig for Life magazine. He’s traded them in for white cactus blooms and abstract vaqueros. A move from the kitschy New York pop art world to the windswept mesa of the Hopi reservation in Hotevilla, Arizona, will do that to you.

Even if it was only for the summer.

It took Mell only a year after experiencing “one of the most peaceful places on earth” before he left New York City and joined forces with one of his brothers, opening the Twin Palms Studio in Phoenix. The studio would not be Mell’s last, but his growth as an artist was much like his newfound haven. Angular mountains and muted clouds swirled in his mind’s eye, as though he was a visionary bird, scanning the landscape, while his senses took in the world beneath him.

Such a vision became true in 1980, when Mell met Jerry Foster, who was a news reporter and helicopter pilot for Phoenix’s KPNX-TV. Using a small Hughes 500E helicopter, Foster flew Mell to the highest point in Arizona, Mount Humphreys, to the canyons around Lake Powell and to the Utah-Arizona border straddler, Navajo Mountain.

With over 1,000 photographs from that trip, and many more from subsequent others, Mell says he “could paint the rest of [his] life from the images obtained on those trips.”

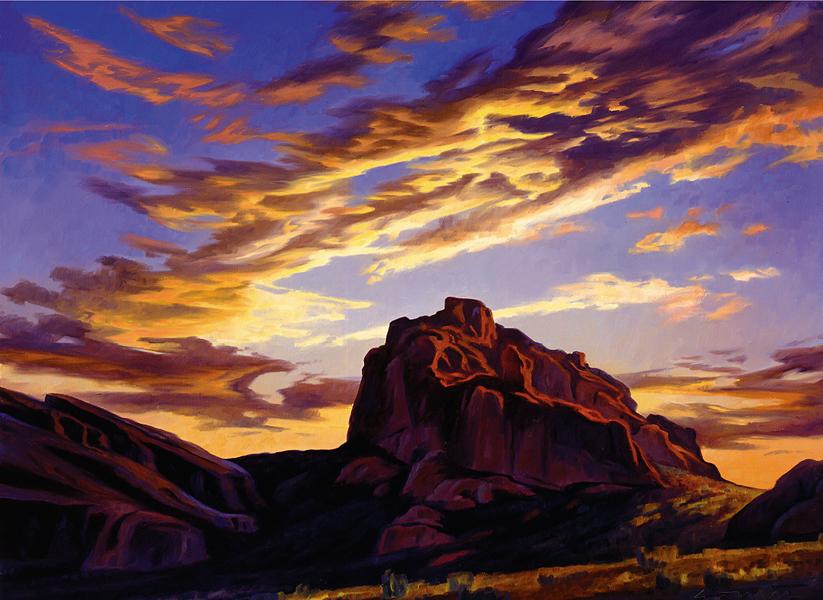

But a fluid artist takes on many forms. Mell’s artwork has jumped from minimalist landscapes to “architectonic”; from cubist cowboys and horses to visual gardens; and from clouds, the “roofs of the land,” as one of Mell’s favorite artists Maynard Dixon (see Art of the True West, Nov/Dec 2003) once said, to imagined realms where landscapes take on qualities of their real counterparts but are not actually of this earth.

Hagerty describes Mell’s landscape work best: “No human presence intrudes upon his art, yet the human spirit reverberates in his work.”

But even when a Western character steps on the scene, each and every line throbs with a pulse that only one man could give—and not miss a beat.

Photo Gallery

– By Robert Ray –

– All artwork courtesy Ed Mell except otherwise noted –

– Courtesy Collection of Arnold Schwarzenegger –

– Courtesy Raymond E. Johnson’s Overland Gallery of Fine Art –