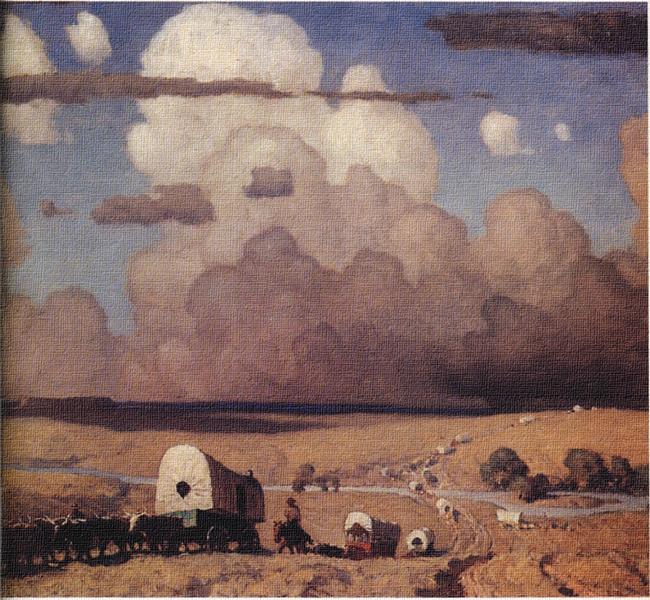

America turned to its own “camel of the prairie” to expand west—not a humped animal that could withstand the desert, as we normally think of camels, but a small wooden wagon that carried some 400,000 people west between 1843-70.

America turned to its own “camel of the prairie” to expand west—not a humped animal that could withstand the desert, as we normally think of camels, but a small wooden wagon that carried some 400,000 people west between 1843-70.

To this day, the romance of the wagon train lives on, and several outfitters offer wagon train vacations. But read any book about the reality of westward emigration, and you’ll discover there wasn’t much romance in those small wagons that held every precious possession for a new life.

The typical wagon was 10 feet long, 4 feet wide and 2 feet deep, and then had hoops over which canvas was stretched. Most of the freight and people traveling westward until 1850 did so in a Conestoga wagon invented by the Pennsylvania Dutch and named for the valley where it was first built in the 1700s.

After the Conestoga came a smaller, sleeker “prairie schooner”—so named because, from a distance, its white top looked like ship sails.

“No Sunday West of Omaha”

Wagon trains always left in the spring so they could clear the high mountains before snowfall. And once they started, they didn’t stop. Wagons traveled 12 to 20 miles a day, seven days a week, since, as the saying went, “there was no Sunday west of Omaha.” The day began before dawn when the livestock were rounded up and the teams of oxen were hitched. Meanwhile, breakfast—bread and coffee—was made.

The emigrants traveled nonstop until?“nooning”—the midday break for dinner and rest—and continued on for a full afternoon before camping for the night, when wagons were often formed in a circle for protection.

All day long, milk from accompanying cows swung to and fro from a crock under the wagon, so by suppertime, there was fresh butter. A simple evening meal was prepared over a campfire, the bread or biscuits baking, the dried beans in a pot and, if there was meat, a crude spit holding the carcass. There were no fresh vegetables or fruit.

Sometimes after supper there was fiddle music and a dance, but usually, the emigrants were so exhausted, they just bedded down.

Middle Class Pioneers

“Poor people rarely migrated,” wrote Gail Collins in her 2003 book, America’s Women. “Buying and outfitting a wagon cost between $600 and $1,000 at a time when a factory worker might make $300 a year, so pioneer wives were generally middle class. They certainly thought of themselves as ladies. Most rode sidesaddle during the trip, with one leg hooked over the pommel and their long skirts covering their legs.”

Many migrating women were also pregnant, but they were still expected to carry their own weight in moving the train along.

In the end, only the most crucial items remained on the wagons, as it became necessary to discard more and more when the terrain became rougher and the oxen or mules became weaker. Collins quotes one woman’s journal: “Boxes and trunks of clothing were thrown out, chests of costly medicine … cooking utensils, cooking stoves, vessels of every description … in fact, you can name nothing that was not lost along this road.”

But those who found the end of the trail often used their covered wagon as their first homestead shelter. When a sod house or log cabin was finally built, the wooden wagon became the family’s mode of transportation, while the canvas that had once provided shelter from the elements was cut up and used for everything from curtains to shirts.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –