“I was a very small child when the first white people came into our country. They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and have continued so ever since, and I have never forgotten their first coming.”

“I was a very small child when the first white people came into our country. They came like a lion, yes, like a roaring lion, and have continued so ever since, and I have never forgotten their first coming.”

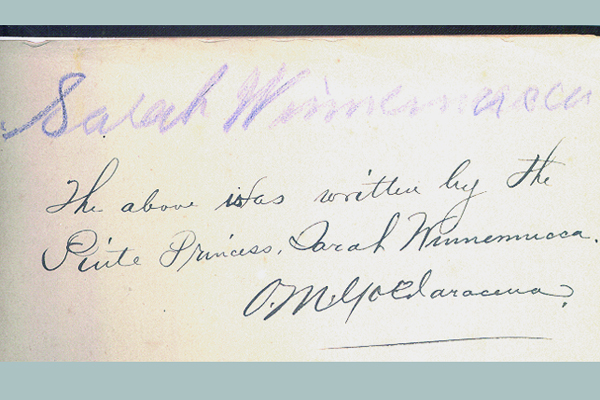

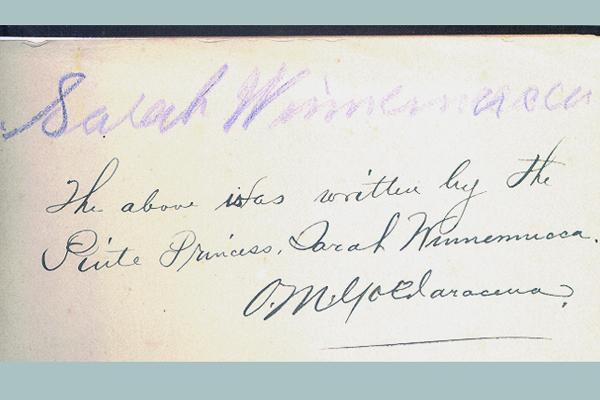

Sarah Winnemucca wrote those words in her 1883 autobiography, certainly the first book ever published by a Native American woman, and one of the first by any Indian in the nation.

This civil rights leader, educator and tireless advocate for her Paiute tribe stands to this day as one of the three most important Indian women of early America. Along with Pocahontas (who befriended the English citizens of the Jamestown Colony) and Sacagawea (who helped guide the Lewis and Clark expedition), “Princess Sarah” opened at least some eyes to the injustices being done to Indians while the West was being settled. As biographer Sally Zanjani puts it in her 2001 book, Sarah Winnemucca, “She gave voice to the voiceless. She made the plight of an obscure Indian tribe a matter of public concern. By her example, she disproved the racist notion that Indians were subhuman and could not be taught.”

Sarah was born around 1844 of Paiute royalty—both her grandfather and father were chiefs of the Paiute Nation (then spelled Piute) that covered most of what is now Nevada. Her grandfather rejoiced in the coming of the white man, seeing it as fulfilling an ancient Paiute tale that prophesied lasting peace once the tribe was reunited with its “lost white brothers.” He proudly wore the name an army general gave him—Chief Truckee, after an Indian word that means all right or very well. Sarah’s father, however, was leery of what this ever-growing migration of whites meant. Horrific stories spreading from tribe to tribe—including the cannibalism of the Donner party in the nearby Sierra Nevada Mountains—convinced him these newcomers were not to be trusted.

Sarah would never forget the first coming of the white man because it was such a terrifying experience. To quote from her autobiography:

“What a fright we all got one morning to hear some white people were coming. Every one ran as best they could…. My aunt overtook us and she said to my mother: ‘Let us bury our girls, or we shall all be killed and eaten up’. So they went to work and buried us and told us if we heard any noise not to cry out, for if we did they would surely kill us and eat us…. Can any one imagine my feelings buried alive, thinking every minute that I was to be unburied and eaten up by the people that my grandfather loved so much? With my heart throbbing, and not daring to breathe, we lay there all day.”

Sarah would become a self-educated woman. Her grandfather wanted her educated with white children and sent her to a California mission school in 1860, but white parents objected to their children studying with Indians, and Sarah was forced out. Although her spelling would always be atrocious, she was conversant in two languages, which helped her earn a living: first as an interpreter for the army and then for a benevolent Indian agent (the only one she ever encountered).

In 1883, Sarah went on the lecture circuit, finding willing ears among Eastern liberals. (She was accompanied by her third husband, Lewis Hopkins, who would gamble away much of her earnings.) She was not afraid to name names as she recited the sins of the reservation system with its tyrannical agents. She pleaded for Indians to control their own reservations—an idea that was a century too early.

Her straightforward, often fiery words didn’t sit well with everyone. One monthly journal tried to discredit her as “an Amazonian champion of the Army” who was nothing but “a common camp follower.” But many saw through the campaign. For herself, Sarah said, “Everyone knows what a woman must suffer who undertakes to act against bad men.”

In 1885, she founded a school for Paiute children in Nevada to fulfill her vision that education was the key to her people’s success in the new white world. The school ultimately failed, much to her dismay.

That same year, Sarah took her lecture tour to San Francisco, California, where she was warmly received and touted by a newspaper: “In the history of Indians, she and Pocahontas will be the principal female characters, and her singular devotion to her race will no doubt be chronicled as an illustration of the better traits of the Indian character.”

To this day, her position in Paiute history is mixed: some condemn her as an assimilationist who married white men; others see her as a strong woman who fought for her people.

Sarah Winnemucca died on October 17, 1891. In 1994, a Reno, Nevada, elementary school was named in her honor. Posthumously, she was awarded the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame Award in 1993 for her autobiography.