Got to go tomahawk Kaiser Bill!”

Got to go tomahawk Kaiser Bill!”

These words from the WWI ditty about fighting against Kaiser Wilhelm II’s Germany, sung as an American Indian by white songster Billy Murray, speak volumes about the tomahawk, one of the most iconic weapons of Indians.

The word “tomahawk,” sometimes simply called a “hawk,” was introduced into the English language during the 17th century. It is derived from the Powhatan Algonquian word “tamahaac,” which, in turn, comes from the Proto-Algonquian root “temah,” meaning “to cut off by tool,” or by an axe.

Because Indians lacked metal working technology before Europeans arrived in the Americas in 1492 and colonization began, they crafted aboriginal implements—used for chopping, cutting or hunting, and as a weapon—made from either rounded stones or pieces of deer antler secured to a wooden handle by strips of rawhide.

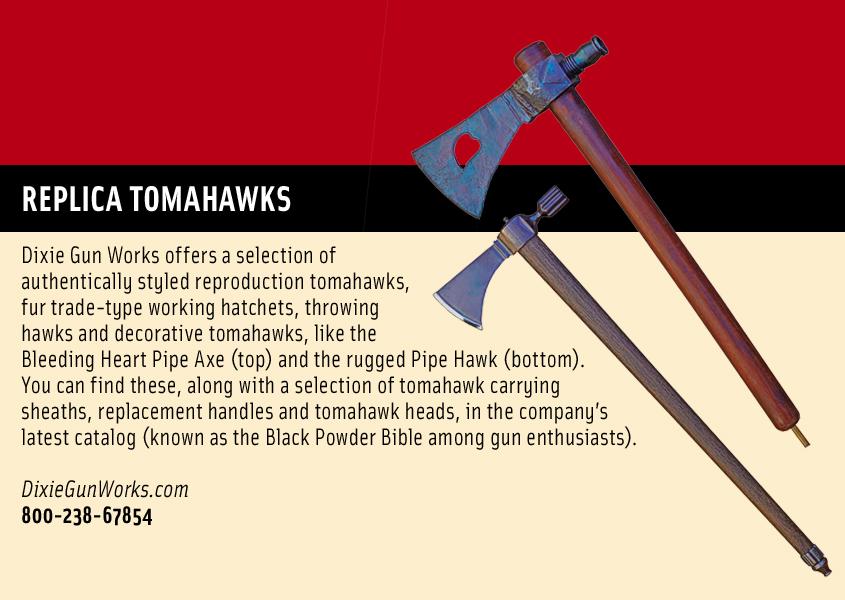

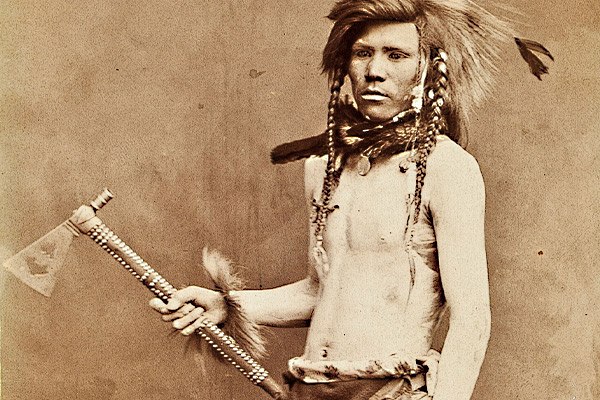

The first contact with white traders brought natives the more durable iron axe (called “hatchet,” “hachotz” or “hatchette” by the early Eastern explorers) and especially tomahawks with their hammer, spike or bowl on the poll end opposite the blade and its hollowed opening in the head for the shaft. A serviceable tool for daily chores, as well as for throwing, hand-to-hand combat or smoking, these combination tool-weapons immediately became one of the most highly prized items of barter with Indians out West.

While the first iron hatchets and tomahawks in America came from British and French sources in the northwestern territories and the Spaniards and French in the south and southwestern regions of the frontier, the first American tomahawks probably appeared in the Far West during Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s 1804-1806 expedition. Nevertheless, by the early to mid-19th century, the iron tomahawk had become a standard trade item and fighting implement of frontier Indians.

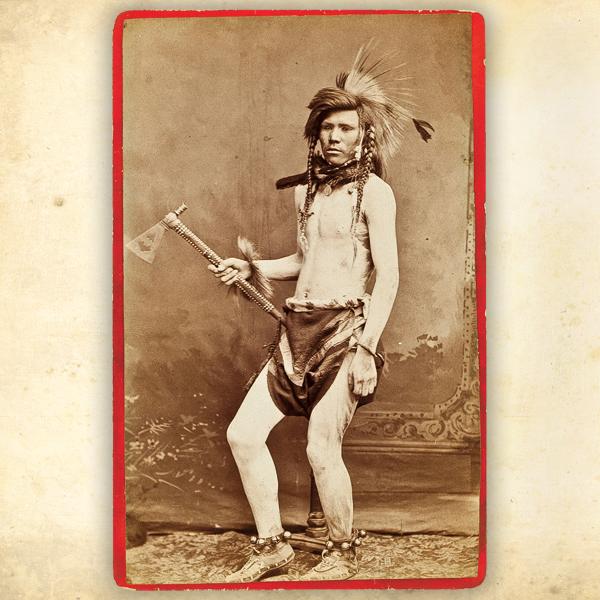

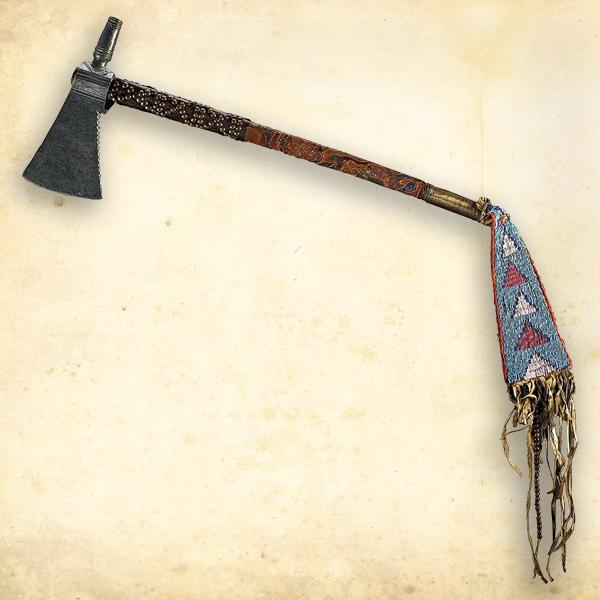

The pipe tomahawk, probably the most revered version of this combination utility, ceremonial and fighting axe, consisted of a bowl opposite the blade and a hollowed out shaft that could be used as a ceremonial smoking pipe, as well as a weapon. It was highly prized as a gift or for trade purposes.

The spiked tomahawk, made along the lines of medieval European battle axes, had either a straight or curved spike projection at the top of the hatchet’s head.

The Missouri war axe, a large, thin-bladed hatchet with a short handle, was favored by tribes along the great bend of the Missouri River.

The spontoon tomahawk, with its dagger-like blade and curled or winged-like appendages, suggested a fleur-de-lis-shaped battle axe.

Although least practical as a cutting or chopping tool, each one of these tomahawks made formidable hand weapons and held some favor with Indians because of their graceful and artistic shapes.

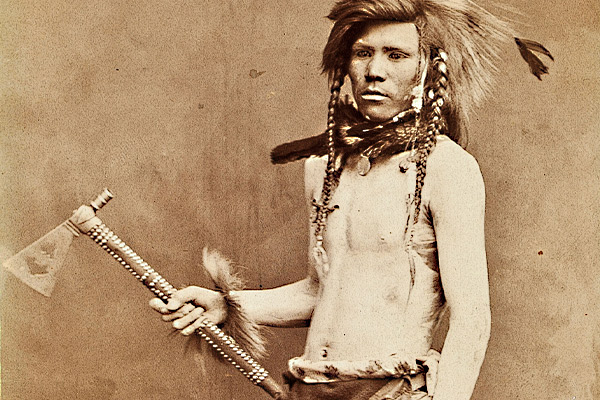

Regardless of style or shape, like the Indian’s bow and lance or the white man’s rifle and revolver, the tomahawk was as important a practical tool as it was a weapon of combat. Whether left plain or adorned with tacks, beads, colored cloth, feathers, animal parts or even human appendages, the tomahawk also served as a symbol, representing the choice between peace or war, when white and red men met: one end was the pipe of peace; the other, an axe of war.

Phil Spangenberger has written for Guns & Ammo, appears on the History Channel and other documentary networks, produces Wild West shows, is a Hollywood gun coach and character actor, and is True West’s Firearms Editor.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Bob Coronato of Rogues Gallery –