Because we are dealing with a legend everyone seems to feel that it must be authentic. I am not interested in authenticity. I am interested in drama.

Because we are dealing with a legend everyone seems to feel that it must be authentic. I am not interested in authenticity. I am interested in drama.

—Sam Peckinpah

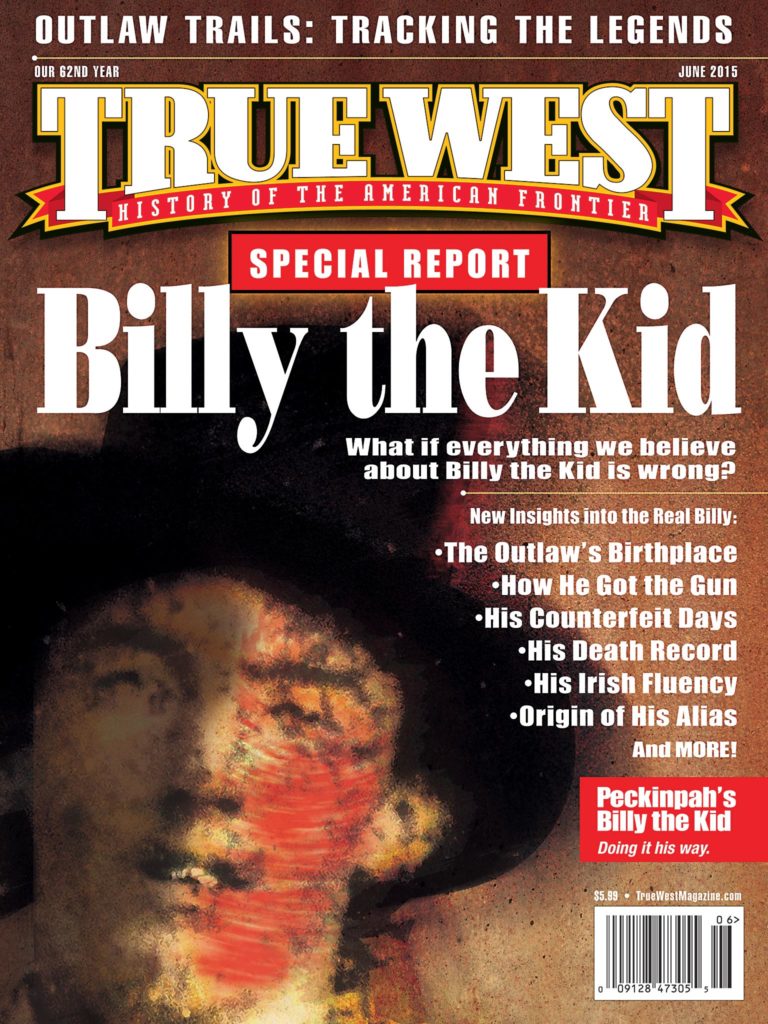

Sam Peckinpah’s last Western film is the only one he ever made about actual historical figures of the Old West, men who, like Peckinpah himself, were in the process of becoming legends even while they lived. It is practically beyond argument that Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is by far the best and most important of the 50-plus films about Billy the Kid. But is the 1973 movie historically accurate?

Director Peckinpah thought so, but by this he seems mostly to have meant that he felt he had depicted the Kid as a killer rather as a hero.

Screenwriter Rudy Wurlitzer thought so too, but he seems to have meant only that by concentrating on the last three months of the Kid’s life when, he believed, nobody knew exactly what the Kid was up to, he could be freely inventive without being false to history.

In fact, the Kid was more than just a killer and quite a lot is known about what both he and Garrett were doing those last three months, and little of it is portrayed with anything like strict accuracy in the film.

Does This Matter?

The question of historical accuracy as regards works of the imagination is in many ways a silly one. People who want history should read histories and biographies or watch documentaries. Novels, plays and films will always invent, distort or falsify because their priorities consist not in fidelity to facts, but in telling good stories.

Using facts as a kind of counter by which to club storytellers is a game the historian critic is always going to win because adapting history to fiction, drama or film always involves more elimination than inclusion, more reduction than expansion: composite characters have to be created; events discarded, changed, reordered or invented for the purposes of structure and plot (which life is all too rarely solicitous enough to supply); most problematic, perhaps because most susceptible of distortion, is the need to find a theme in the historical materials.

Storytellers are always going to try to find their own meaning in the material, which is something that history doesn’t necessarily furnish. By this I don’t necessarily mean a paraphrasable idea, though it could be that too, so much as a perspective or view of the material—that is, some idea, perception or emotion—that offers an entrée into it and a way of approaching, shaping and organizing it.

And when we have a writer with as distinctive a style as Wurlitzer’s, to say nothing of Peckinpah’s as a filmmaker—well, still less do we have any business expecting, let alone demanding, what is vulgarly called a biopic or a docudrama.

Shining a Light on History

One fairer question might be, does the story illuminate the history in ways that are valid as interpretations or simply as imaginative leaps that are revealing of certain kinds of truths unavailable by any other means?

The answer with respect to Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a very easy yes. What we might call the film’s synoptic view of the events is more than amply corroborated by the most reliable historians, starting with Maurice Fulton, who wrote, “Scratch beneath the surface and you will find one thing as the prime mover in most of the Lincoln County troubles—money.”

Wurlitzer, with Peckinpah’s blessing, made this explicit in the scene with the men who represent the collusion of investors and land speculators who make up New Mexico’s Santa Fe Ring, while its setting in the governor’s hacienda adds politics to the mix. Throughout the rest of the film, these forces of commerce and big business in collusion with government are periodically referenced, their iron grip strongly implied.

The relationship between Lincoln County and the territorial government in Santa Fe allowed the filmmakers to give this theme an unmistakably contemporary slant, indeed a prescient one, because through so much of the conflict, Thomas B. Catron and his associates in the Santa Fe Ring remained background figures, aloof and detached, even as they controlled the purse strings and gave orders to Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, owners of the general store known as the House.

The Watergate scandal did not break big early enough to have had much influence as such on the development of the screenplay, but by the spring of 1973, Peckinpah alluded to it in the note he appended to the end of the second preview. Even without that, however, there is enough in the Territorial Gov. Lew Wallace scene and elsewhere to suggest a society infected by corruption and ruled by powerful, insulated conspirators who commit high crimes and misdemeanors with impunity.

In Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, figures like the land baron exist, but they are never seen; indeed, they’re not even named or otherwise identified. When their lackeys refer to them, it is in a passive construction that makes them seem like inhuman, impersonal forces, so our attention is directed instead to the men they control like pawns: “[John] Chisum and the others have been advised to recognize their position.”

The film has a particular resonance in our own time of multinational conglomerates where nobody seems to know who is in charge or can be held responsible for anything. I can’t think of another retelling of the story of Garrett and the Kid that views the history in quite this way, but it is just one more example of what can be done with these materials if only you have writers and directors imaginative enough to do it.

Sadness and Tragedy

A big part of what drew both Peckinpah and Wurlitzer to depict this history is that, as the writer put it, “everybody knew everybody. That’s where a lot of the sadness and tragedy come in.”

No one has come close to inflecting this with as much pathos as Peckinpah does in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: scene after scene plays out as farewells, leave-takings, goodbyes, some peaceable, most violent, as individuals or groups find themselves in oppositions that didn’t exist a few months ago and may not a few months hence, but they do right then, and so by violent attrition a way of life slowly, almost casually disintegrates before our eyes.

Peckinpah’s special achievement in this film is his depiction of the death of the Old West, so tough minded, yet so elegiac, which continually forces us to question its values, its very worth, even as we are moved by its loss.

Because everybody knew everybody else, Peckinpah also believed that the idea of directness—if not honor, then at least forthrightness among thieves—was a practical value these people lived by, not merely a romantic myth.

“When Billy switched from Dolan to [John] Tunstall,” the director stated, “he told his former buddies he was making the switch.”

Peckinpah was here alluding to chapter eight from the Ash Upson part of The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, where Billy rides out to inform Jesse Evans and the Boys that henceforth he was going to be working for Lincoln County rancher and merchant Tunstall (who would become the first man killed in what developed into the Lincoln County War).

Almost nobody believes this incident occurred—if it occurred at all—anything like as melodramatically as Upson imagined it. I personally don’t think Peckinpah believed it either, but he seemed to have believed there was sufficient historical basis behind it for him to want the idea of it sounded in his film.

The first scene in Fort Sumner he intended precisely to dramatize the point that Garrett takes the time and expends the effort to make the ride from Lincoln to inform the Kid and his gang directly and in person that he’s now sheriff and that his new responsibilities include clearing the territory of outlaws and rustlers.

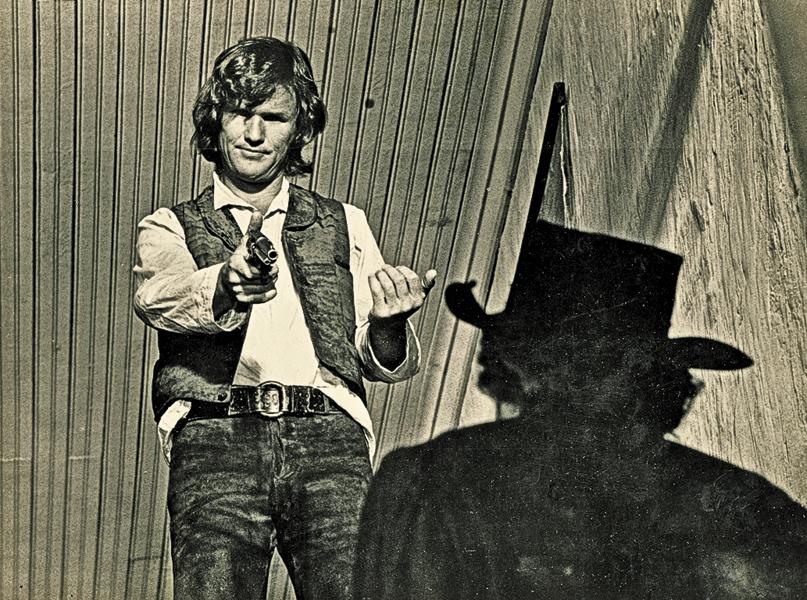

Although this scene never took place in history, the sheriff character as conceived by Peckinpah and Wurlitzer, and played by James Coburn, is nevertheless a remarkably credible dramatic embodiment of the historical figure, especially the Garrett seen in the prologue: the disillusioned, irascible, hot tempered ex-lawman, surrounded by people he detests, is easily recognizable from his historical counterpart, who spent his last bitter years in debt pursuing one failing moneymaking scheme after another.

Garrett’s Story

Peckinpah has long and rightfully been credited with making Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid far more Garrett’s story than the Kid’s. I can’t state for certain that Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is the first and only fictional treatment to place Garrett center stage and in top position, but I don’t know of another.

At the outset, dramatic irony as it applies to the Kid consists in our knowledge that he will die, but it’s an event that we don’t experience until the very end. With Garrett, however, the effect is far more powerful because we are actually shown his death at the outset—more than just shown it, in fact, but made to experience it with him.

Peckinpah went even further by intercutting Garrett’s murder with the new Fort Sumner scene. The crosscutting between Garrett’s body being riddled with his murderers’ bullets and the buried chickens getting their heads shot off by the Kid and a younger Garrett 27 years earlier makes Garrett himself one of the instruments by which fate will cut him down as surely as it will the Kid, though it will take nearly three decades longer.

As realized on film, the crosscutting has the additional effect not just of reorienting the film toward Garrett, but also of making it his in an unusually direct and intimate way, such that it conditions our response to everything that follows. In effect, it established the point of view as Garrett’s.

I do not mean this literally, of course, only that despite the alternating back and forth between the two principals once they’ve gone their separate ways, emotionally and psychologically the film remains Garrett’s through and through.

By the time Peckinpah was finished, the Kid was so thoroughly absorbed into Garrett’s psyche as a conflicting side of Garrett’s personality that Billy all but ceased to exist as a character in his own right, or at least as a character with any sort of internal consistency.

The only tie that cannot be severed and that will survive even the finality of death is the fate that binds together the outlaw and the lawman: if ever two men shared a fixed purpose on a path laid with iron rails on which their souls were grooved to run, they were Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Yet in this fine, compressed, almost unendurably dark film, it is a purpose without apparent motive, a path without apparent design, a determinism that serves no higher plan in a world without apparent meaning.

This is an edited excerpt from Paul Seydor’s The Authentic Death & Contentious Afterlife of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid: The Untold Story of Peckinpah’s Last Western Film, published this year by Northwestern University Press.

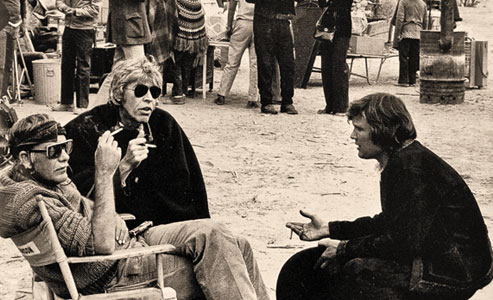

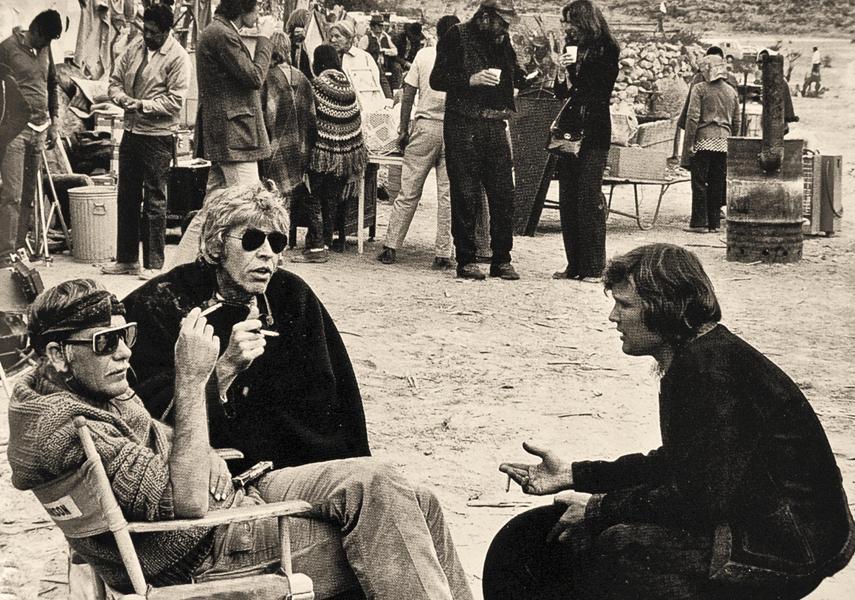

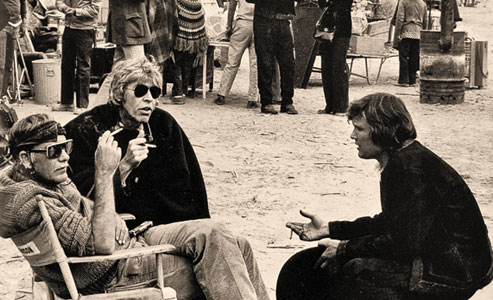

Photo Gallery

– All images Courtesy MGM, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid –