John C. Holgate died first, pistol in hand, leading his men down a smoke-filled mining shaft.

John C. Holgate died first, pistol in hand, leading his men down a smoke-filled mining shaft.

J. Marion More was gunned down in the streets of Silver City, Idaho—his supporters said murdered—only two days after signing a truce to end one of the era’s most violent mining conflicts.

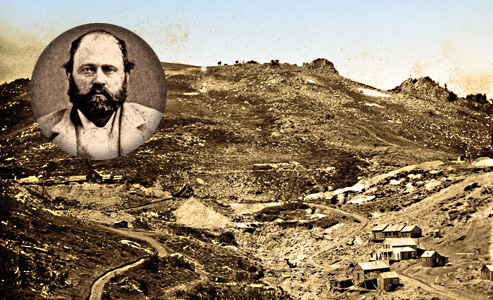

Prominent pioneers of Idaho’s gold rush, both men fell victim to a dispute over what one 1867 visitor called the “richest and most wonderful deposit of quartz yet discovered in the United States—even eclipsing the famed Comstock Lode of Nevada.”

The Breach

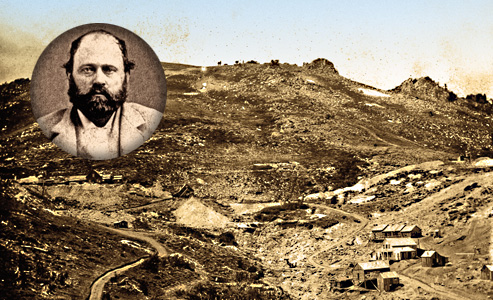

War Eagle Mountain rises 8,000 feet above southwestern Idaho’s Owyhee Desert. The earliest lode discovery at War Eagle was the incredibly rich Oro Fino, near Silver City. Other mines quickly started nearby, including the Golden Chariot and the Ida Elmore.

Holgate, Hilary “Hill” Beachy and George Grayson owned the Golden Chariot. More owned the Ida Elmore with Col. D.H. Fogus. Born John Neptune Marion Moore in 1830, he had fled the California goldfields under mysterious circumstances and changed his name to J. Marion More.

The surface claims of the two mines overlapped—not an unusual circumstance for the times. When two shafts, being driven from opposite sides of the same ridge, intersected, the mines established neutral ground to separate the operations.

Then in 1868, someone breached the thin wall of rock separating the two shafts. Both parties claimed that the other had left its legitimate ore vein and entered into the competitor’s lode.

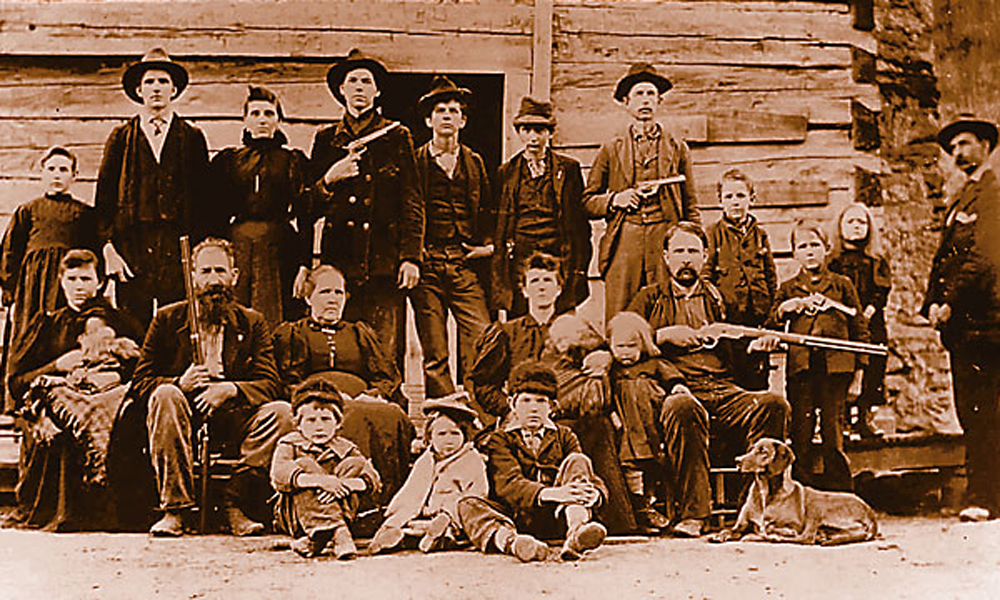

At 300 feet below the surface, the mining crews quickly formed hard feelings. The law was distant and slow, and a single day’s output of ore meant thousands of dollars. Both sides armed themselves, with both also claiming the other had done it first, and they had responded in self-defense.

The two mines became armed camps, with more than 100 men at hand—at least half had no duties other than fighting. “Barricades were erected; side pits were cut out along the drifts and levels as shelter for these guards…. Arms of all kinds—rifles, shotguns and pistols—were imported by the case and each [mine] had a magazine of ammunition within its works,” one newspaper account stated.

Gunshots in Dark Passages

Violence soon flared, as each crew attempted to capture the works of the other. Whenever a light appeared within the tunnels, it was greeted by rifle and pistol fire. A reporter from The Owyhee Avalanche went to see for himself:

“Went down into the Golden Chariot and saw the ‘bone of contention’—the place where the partition wall was broken down and the workmen in both mines met. The lights were extinguished, and we skedaddled, as we heard the reports of guns and pistols reverberating through the long dark passages. The fight had commenced. We felt considerably relieved upon gaining the surface of the ground and once more beholding the light of day.”

The first casualties were not long in coming. The most prominent was Holgate, of the Golden Chariot. A Pacific Northwest explorer and prospector, Holgate was often called the “first settler of Seattle.”

Like many aspects of the conflict, the details of Holgate’s death are disputed. The Owyhee Avalanche reported that, on March 25, 1868, Golden Chariot miners attempted to overpower the other side through a mine tunnel. “Desperate fighting ensued during the charge…John C. Holgate…one of the foremost in the advance, was shot in the head, and must have died instantaneously.”

The Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman reported a different story: “Our community has been startled several times during the last three days by the most exaggerated rumors of battles and bloodshed between the Beachy & Grayson party and the Fogus party. We have taken some pains to arrive at the truth of the case as nearly as we could. It appears that J.C. Holgate has been killed, some say assassinated, murdered—not killed in a fight, but shot through the head without provocation.”

Fighting came to a head on March 27, when the Golden Chariot crew drove their opponents from the mines. The battle continued on the surface. A lull on Saturday and Sunday was not a sign of the end, but merely that the men were waiting for reinforcements to arrive.

The Truce

Idaho territorial Gov. David W. Ballard, alarmed by reports of high casualties and extreme violence, issued a proclamation on Saturday night, March 28. He commanded all to cease the violence, and he reminded the mining crews that “banding themselves together in armed parties to either commit aggressions or to resist them from similar parties is in violation of the law, subjects them to heavy punishment, endangers the public peace, and tarnishes the fair name of our Territory.”

To back his words with iron, Ballard dispatched 150 U.S. Army troops from Fort Boise. These soldiers were due to arrive on April 5.

Deputy U.S. Marshal Orlando “Rube” Robbins left Boise immediately to serve the governor’s proclamation to the belligerents. He arrived early the next day, March 29, after a six-hour ride. Within 60 minutes of his arrival, he had brought the principals to the table. By 2 p.m. on Monday, the parties had reached an agreement, exchanged deeds and driven stakes between the competing claims. The armed men withdrew and dispersed.

John R. McBride, chief justice of the Territorial Supreme Court, arrived in Silver City on April 1. He found an atmosphere of calm and “general rejoicing”—but this was not to last.

Respite Broken

McBride settled into quarters on the second floor of the Idaho Hotel for the night. Within an hour, shots rang out.

“The cause was soon explained,” McBride stated. “Marion More was shot mortally, and two others wounded.

“A few minutes after I heard a rush of feet on the porch below. A crowd rushed up the stairway. I opened the door and saw Beachy and two others busy loading rifles and firearms, and a man by the name of Sam Lockhart, a friend of Beachy, holding a disabled arm, from which blood was dripping.

“In front of the hotel an angry mob was gathering and voices wild with passion and loud with threats and cursing filled the air. ‘Bring him out; Hang him!’ yelled the crowd.

“As Beachy rapidly loaded weapon after weapon, he exclaimed, ‘The man who comes to take Lockhart out of this hotel without a warrant, will die before he reaches the head of the stairs!’”

Ida Elmore’s Owner Goes Down

Before he met his maker, More had been enjoying a celebratory meal with friends and had drunk heavily. Drink made the generally quiet man quite irritable. After he finished his meal, he met Lockhart and another Golden Chariot man on the street. They exchanged words.

More was unarmed, but he carried a rough cane. He raised it as if to strike Lockhart, who backed away a pace, drew his pistol and shot More in the chest.

Ben White and Jack Fisher, More’s friends, drew their weapons. White’s pistol misfired, but Fisher’s shot struck Lockhart in the arm. Lockhart shot again and struck Fisher in the leg.

Lockhart later insisted that Fisher had fired first, and that he had fired only after being shot in the arm.

More staggered 50 yards down the street and collapsed in front of the Oriental Restaurant.

McBride came down from the hotel and went to More’s side. “He had been shot in the breast, the ball penetrating the lungs, and he was rapidly failing,” he recalled. “He was able to converse in a faint voice and recognized me when I took his hand and spoke to him. He said; ‘They have stolen the mine and now their man Lockhart has killed me.’”

More died three hours later.

The gunman, Lockhart, was described contradictorily in the newspapers.

Lockhart was a “man known as a very desperate character, who has been employed in Nevada for years past, to fight for contending mining claimants, and who was brought from that State by the Golden Chariot party to engage in the late war on the mountain,” The Idaho World reported.

The Owyhee Avalanche defended Lockhart as “never known to begin a quarrel with anyone; is no ‘desperado’ or rough, unless these terms be applied to a peaceful citizen because he fights for his life when assailed.”

Lockhart’s arm wound eventually turned to gangrene and had to be amputated. Blood poisoning then set in, and the gunman succumbed to death on July 13.

The End Finally Comes

To prevent a return to all-out war, authorities placed all participants in the shooting under arrest and questioned them until Lockhart’s guilt was established.

“So the Owyhee War ended,” wrote a somber Judge McBride, who later took a personal tour of the mine shafts where the fighting had occurred.

“On one level there was a heavy timber used as a support for the roof, probably fifteen inches in diameter. It was filled with bullets and had been so frequently struck and pierced that at one place about two or three feet from the floor it was cut nearly in two. It was said that this one piece of timber had been struck by two thousand bullets,” he wrote.

The bullet-laden beam served as a fitting monument to Idaho Territory’s most unusual and violent mining episode.

Robert L. Deen is the author of Owyhee County, an Arcadia book published this May that features photography from the Owyhee County Historical Society.

Photo Gallery

– All photos courtesy Robert L. Deen –