May 7, 1896

May 7, 1896

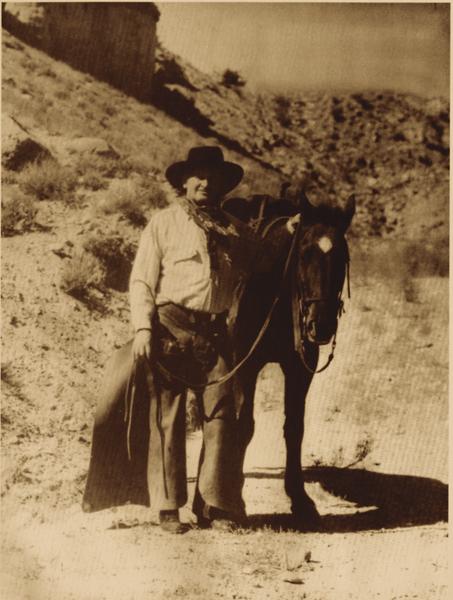

Hired to scare off pesky, potential claim jumpers, gunman and known outlaw Matt Warner and gambler William Wall accompany mining man E.B. Coleman up into the mountains above Vernal, Utah.

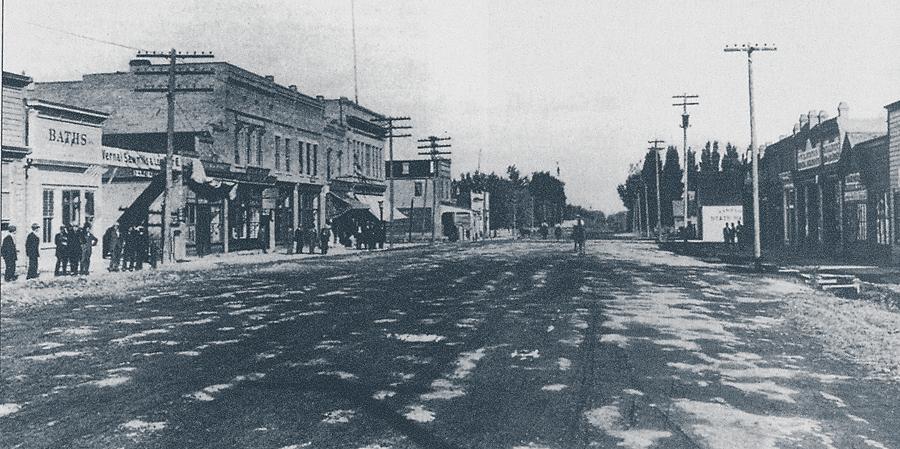

The day before, Coleman approached Warner in a saloon in Vernal, offering him $100 (some sources state $500) to scare off some prospectors who were following him. He had gone to Dry Fork to look for copper showings, but he discovered some men—the Staunton Brothers and Dave Milton—following him. He even offered to buy them off, but they stayed right on his trail, camping where he camped.

Warner agreed to the job, bringing along his acquaintance, gambler Bill Wall. The trio left that night, but Coleman lost his trail, and the men were forced to camp.

Around daybreak, Warner and Wall brandish their weapons and charge the Staunton Brothers’ camp near Dry Fork. They see Ike Staunton building a fire outside of the tent.

Ike notices the approaching riders and yells to his pards, “Get up, they’re coming for us.” He grabs his rifle and fires a warning shot at the riders.

Wall and Warner open fire on the tent, while Ike scrambles for cover behind some aspen trees.

Shooting out the back of the tent, Milton kills Warner’s horse. Dick Staunton runs out of the tent, shooting, only to be hit by a bullet. He falls backward into the tent.

Shielded by aspen trees, Ike exchanges gunshots with Warner and Wall, who are 30 yards away from him.

Ike, firing a single shot rifle, picks away at the center of Warner’s aspen tree, some 15 inches thick. He blasts a spot about the size of a dollar coin, with the idea of boring a hole clean through with another shot.

Realizing the ploy, Warner finds himself in a tight spot. Wall finally gets in a shot at Ike. The bullet hits Ike just across the bridge of the nose, filling his eyes with blood and knocking him senseless.

The fight is over.

Matt Warner’s Version of the Fight

“Bill [Wall] and me rode across the sagebrush flat and up in front of the camp as innocent as babes. Bill was a ways behind me. I noticed the pile of logs and poles with the canvas spread over them at the edge of the timber, but didn’t think anything about it. When I was about forty feet from the ambush three Winchesters exploded almost in my face and nearly split my ears. With a squeal like a dying man, my pony dropped in his tracks.

“I done the right thing instantly, I guess, as the result of fighting instinct and my experience in gun battles. While my horse is falling I grab my .30-30 Marlin repeating rifle from the scabbard on the saddle with my left hand, my Colt six-shooter from my belt with my right hand, throw my feet out of the stirrups, and land on my feet as he strikes ground. Seeing Milton’s shoulder exposed above a log, I shoot him three times with my six-shooter. Three bullets enter his shoulder in a space no larger than your hand and range down into the body.

“‘God almighty, I’m done for,’ he sort of gasps, and we don’t hear any more from that gent while the fight lasts.

“From then on I do all my shooting with the Marlin, shooting from the level of my hips. In close range rifle shooting you can’t wait to sight your gun from the level of your shoulders. If you are an experienced gun fighter, you can tell by the feel of it how to swing your rifle from your hip level with dead accuracy.

“While I am shooting Milton, Bill Wall is rushing up on his horse firing his six-shooter as fast as he can pull the trigger. That covers me and prevents me for a minute from getting killed by disturbing the aim of the Staunton brothers who are now using their pump guns as fast as they can shoot. Their bullets is [sic] cutting my clothes to pieces. Bill Wall now is close by me setting his horse and is in great danger. I drop my Colt into the holster, sweep Bill off from his horse with one arm, and jump with him behind a quaking aspen tree close by. It is only about fifteen inches in diameter and mighty poor cover for two men.

“While I am jumping behind the quaking aspen, Ike Staunton is leaping behind a small pine tree east of the barricade to get on our flank. He is now about a hundred feet from us. Ike gets ready to jump behind a bigger tree and exposes a knee. I catch it with the tail of my eye and as quick as a wink swing and shoot him through the knee. He sticks to the small tree and keeps on fighting.

“Dick and Ike concentrate their rapid pump-gun fire on the little quaking aspen we are using for cover. Some of their bullets go clear through the wood and bulge the bark on our side of the tree. I hold my fire waiting for one of them to expose some part of his body. Dick Staunton is still behind the barricade. He raises a little with cocked Winchester to get a dead aim on me. For just an instant I see one shoulder and the back of his neck as he sights along the barrel to get a bead on me. I don’t stop to sight, but swing my Marlin at my hips before he can pull the trigger and fire. He is squatting low behind a log, and you wouldn’t know he is hit. He just continues to squat there too paralyzed to fall over. His Winchester rolls out of his hands and lays on the ground cocked.

“While I am shooting Dick Staunton, Ike pokes his nose from behind his tree to get a dead aim on me, and my eye catches the movement. Before he can take the bead on me and pull the trigger, I swing and shoot from the hips without sighting, smashing the bridge of his nose. He lurches forward and falls on his face. His rifle strikes the ground ahead of him and lays there cocked. For the second time in this fight I shoot a man in the split second between the impulse and the pressure of his trigger finger. I win because I have learned in my experience as a gun fighter to shoot accurately with a rifle without sighting.”

Too bad much of this great narrative is untrue. Matt Warner wrote this in the 1930s when the gunfighter myth was a popular narrative in pulp literature.

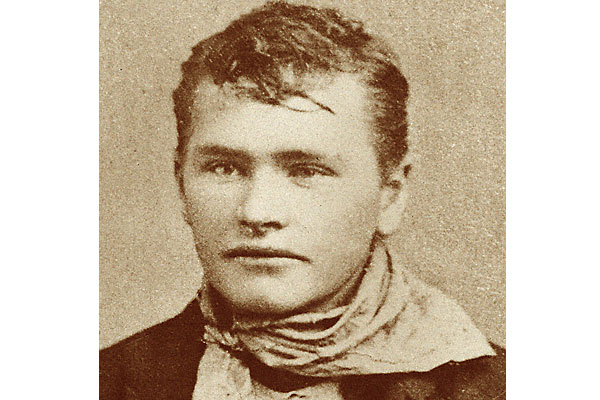

A Man Judged By His Past

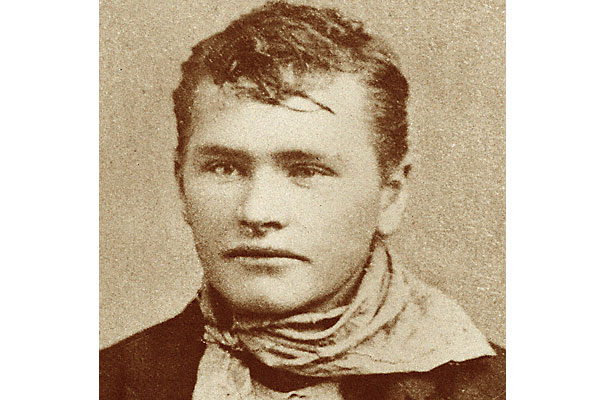

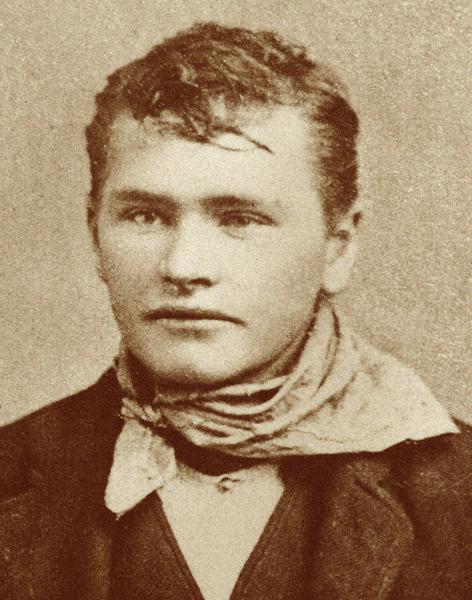

Late in life, Utah badman Matt Warner summed up the odds of his profession: “A man who

has an outlaw past is never safe, no matter how straight he goes afterwards. That’s the price he pays.”

Fleeing home at age 15, after he hit a rival for a girl over the head with a picket fence post, Warner and his bad temper roamed the badlands of Utah and parts of Colorado, where he lived on the edge of the law.

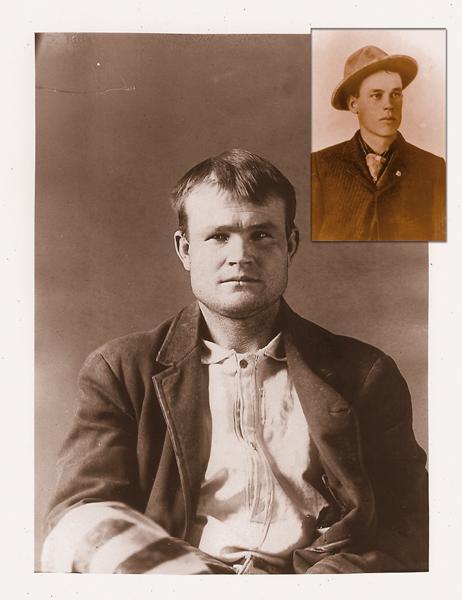

He met Butch Cassidy (then going by his real name Robert Parker) near Telluride, Colorado. The two later teamed up with other cowboys to rob the Telluride bank. By the time mining man E.B. Coleman found Warner in a saloon in Vernal, Utah, Warner had earned quite a name for himself as a hard character.

When Warner and his pard William Wall arrived at the Staunton Brothers’ camp, it seemed almost as if the men had known they were coming; Ike Staunton had immediately shot at their approach.

One version of the story claims the Staunton Brothers were warned by Milton, who trailed Coleman to Vernal and dis-covered the hiring of Warner. Matt Warner’s own account of the gunfight (see previous page) supports the idea of an ambush waiting for them near Dry Fork. The problem with this angle is that two of the men, Dick Staunton and Dave Milton, were inside their tent when the fighting broke out, one of them likely sleeping. Did the trio wait up all night for the Coleman trio, get tired and take a snooze toward dawn?

Even though it appears Ike Staunton fired first (usually solid grounds for self-defense), Matt Warner was correct that his violent past probably weighed heavily in the subsequent verdict.

Butch & Elzy Chip In for the Defense

Butch Cassidy, Elzy Lay and Bob Meeks “withdrew” $7,165 from the bank in Montpelier, Idaho, to help pay legal fees for the Matt Warner-William Wall murder trial.

Butch wrote to Warner’s wife, “Lay and I have got a good man to defend Matt and Wall, and put up plenty of money, too, for Matt and Wall to defend themselves.”

How much of that money actually went to the attorney, Douglas A. Preston, is unknown. The lawyer hotly denied Butch’s statement, claiming his $3,000 retainer was paid before the bank robbery.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

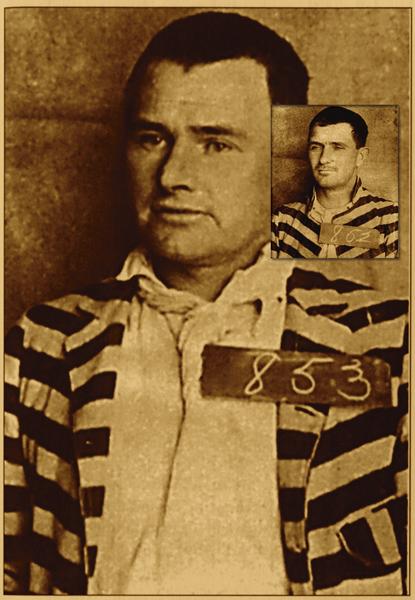

Matt Warner and Bill Wall were convicted of manslaughter (E.B. Coleman was found not guilty). Wall and Warner entered Utah State Prison on September 21, 1896. They served 40 months of a five-year sentence at the Utah State Prison, before being released early for good behavior.

Warner moved to Price, Utah, where he lived out his life as a police officer, deputy sheriff and justice of the peace.

In Warner’s defense, he helped treat the wounded after the shoot-out. He also sent someone to report the shooting to the sheriff in Vernal and request help for the victims—certainly not the actions of a cold-blooded murderer.

Recommended: Last of the Bandit Rivers…Revisited by Matt Warner (updated by Joyce Warner and Dr. Steve Lacy), published by Big Moon Traders; The Wild Bunch at Robbers Roost by Pearl Baker, published by University of Nebraska Press; and 100 Years of Brown’s Park and Diamond Mountain by Dick and Daun DeJournette, self-published.

Photo Gallery

– All images True West Archives –