July 22, 1884

The fuse to one of the West’s most famous feuds is lit a month prior, when Tonto Basin cattleman James Stinson makes a secret pact with the Graham brothers to report on suspected cattle thieves, the Tewksbury clan.

The feud between the Grahams and the Tewksburys exacerbates when Stinson’s agreement becomes public. A trial in Prescott, Arizona Territory, exonerates the Tewksburys.

The stage is set for a reckoning, and it comes soon enough.

On July 22, Tewksbury cowboys spread out as they approach the clearing in front of Stinson’s ranch house in Pleasant Valley, an area also known as Tonto Basin. Around 10 a.m., John Tewksbury, George Blaine, Ed Rose—a friend to both families—and William Richards rein up at the front porch.

Stinson’s cow boss, Marion McCann, tells the unwelcome crew, with the exception of Ed Rose, to move on.

Blaine, offended by McCann’s rebuff, says, “You damned, fly-blowed son-of-a-bitch, I have been bulldozed by you long enough.”

Blaine demands that McCann meet him 50 feet from the house.

With four other Stinson cowboys looking on, McCann obliges, walking confidently out toward the riders.

When McCann gets close enough, Blaine suddenly pulls his pistol and fires. But he misses. In the same instance, McCann draws his own revolver and fires. His shot hits Blaine in the jaw, knocking him off his horse. Luckily, he will survive his wound.

In another muzzle flash, McCann shoots Tewksbury, who jerks his own pistol and fires wildly. Tewksbury reels in the saddle, but manages to avoid being unhorsed, as he and the other riders retreat to a stone wall.

The fight is over, but the repercussions will last for a long, long time.

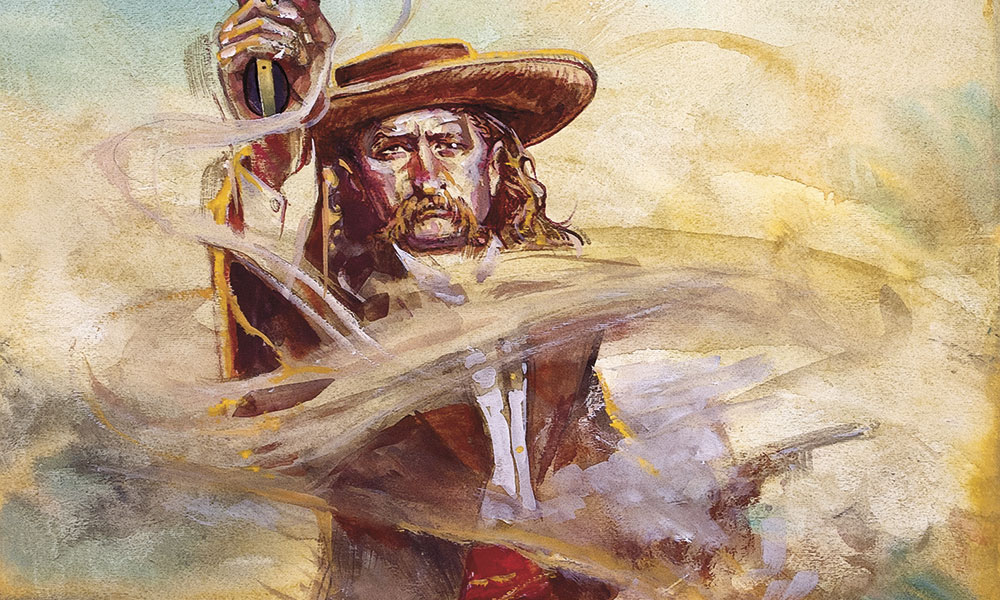

Bad Blood Personified

Bad blood has existed between the two cow outfits for some time. Eighteen months before, the Tewksbury boys killed one of James Stinson’s herders and wounded another severely. A mere 10 days before the shooting on July 22, 1884, George Blaine and John Tewksbury were indicted by the Yavapai grand jury on a charge of stealing cattle, but they were acquitted by trial.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

James Stinson left Arizona and dissolved his herd. In 1885, the Graham brothers found themselves in a tight spot, after significantly losing a great number of their herd and subsequently being caught driving cattle that were not theirs. The feud only got worse when the Tewksburys began bringing in herds of sheep the next year.

John Tewksbury hired a Basque sheepherder to take the sheep to Pleasant Valley. While working on September 2, 1887, he was murdered and robbed by Andy Cooper (a.k.a. Andy Blevins), a member of the Graham faction. Other cattlemen and sheepmen joined in the conflict, either willingly or not.

Unsolved murders of members of both factions occurred. The killings did not stop until Ed Tewksbury and John Rhodes murdered Tom Graham in Tempe in 1892, in broad daylight, in front of numerous witnesses. The jury couldn’t agree to convict. Ed died in Globe in April 1904.

The history of Arizona’s Pleasant Valley War has been written about from various angles and points of view, beginning with Zane Grey’s fictitious account in 1921, To the Last Man and the expanded novel Tonto Basin. In 1936, after spending time in Pleasant Valley, Earle R. Forrest wrote Arizona’s Dark and Bloody Ground. Don Dedera, former columnist for The Arizona Republic, spent more than 30 years researching the history. In 1987, he published his findings in A Little War of Our Own: The Pleasant Valley War Revisited. Leland Hanchett Jr. followed up with two books on the war: Arizona’s Graham-Tewksbury Feud and They Shot Billy Today: The Families of Arizona’s Pleasant Valley War.

Recommended: A Little War of Our Own: The Pleasant Valley Feud Revisited, by Don Dedera, published by Northland Press